Moviemaking is a popular theme in horror fiction. I know of at least one top-notch anthology on the subject—the David J. Schow edited SILVER SCREAM (1988)—and quite a few novels. You might argue that the subject of moviemaking is so inherently horrific genre tropes aren’t needed, as proven by classic non-horror novels on the subject like THE DAY OF THE LOCUST, BOY WONDER and WHITE HUNTER, BLACK HEART, but the following ten horror novels, I’d argue, very nearly match, if not better, those books.

Certainly, there’s plenty of range in the following selection, encompassing many different facets of the movie business as well as a variety of genre accoutrements. You’ll find 1970s nostalgia, B-movie satire and documentary (sur)realism, in addition to aliens, serial killers and cursed films—everything, in short, that any self-respecting film buff or horror maven could possibly desire. So, without further ado…

1. SHOCK FESTIVAL by STEPHEN ROMANO

A large format hardcover documenting the making and reception of 101 nonexistent grindhouse flicks from the 1970s and 80s, with a wealth of multi-lingual poster art for films like LITTLE SISTER’S FACELESS NIGHTMARE, DAY OF THE INSECTS and THE UNDERGROUND TOXIC WASTE MUTANTS. Stephen Romano wrote and largely illustrated the book himself, and has a real talent—genius, even—for capturing the sleazy glitz of trash movie promo art, complete with outrageously hyperbolic taglines (“Fast Cars. Fast Women. Fast Everything”…“She’s Got A Gun! And You Better Run!”). Actual movies like JAWS, STAR WARS and THE TERMINATOR are referenced, blurring the lines between reality and fiction, while the overall timeline, stretching from the drive-in culture of the early seventies to the video revolution of the eighties, is historically accurate. The characters, who include the Italian horrormeister Darby Silver (silver, FYI, is argento in Italian), Russian ingenue-turned-international sex kitten Natalaya Ustinov and ex-Black Panther Tommy Ray Rudy, are a tad more interesting and outrageous than their real-life counterparts, but not by much. Stephen Romano has written other books, scripted graphic novels and designed DVD covers, but I strongly feel it’s SHOCK FESTIVAL that he’ll be remembered for, it being among the most impressive feats of sustained imagination I’ve encountered in quite some time, if not ever.

2. THE DRIVE-IN by JOE R. LANSDALE

Quite simply, one of the wildest, funniest, most outrageous novels of all time. THE DRIVE-IN, written by the incomparable Joe R. Lansdale, relates what occurs when the patrons of a six screen Texas drive-in called The Orbit are taken hostage by aliens bent on making a B-movie epic much like the ones playing on the Orbit’s screens. They cause the drive-in to be closed off from the rest of the world, leaving its redneck patrons to subside on soda, candy, popcorn and a non-stop marathon of trashy horror films. Eventually the aliens transform two especially inhospitable patrons into a monstrous entity called the Popcorn King, who takes to vomiting popcorn with bloodshot eyeballs that make people fall under the PC’s spell. This does nothing to stem the inevitable tide of madness that envelops the Orbit’s clientele, with fights, stabbings, cannibalism and crucifixions quickly becoming the norm. The book is, quite simply, a hoot, with a goodly amount of grue, bad language and a spot-on portrayal of Texas white trash culture.

3. THE BRAVE by GREGORY McDONALD

Full disclosure: this 1991 novel worked me over like no other book in recent memory. The protagonist is Rafael, a 21-year-old drunk who as THE BRAVE opens is talking to a couple of sleazy guys about a “job.” It quickly becomes evident that Rafael is negotiating for the lead in a snuff film that, in a chapter so appalling the author warns us about it in a nonfiction forward (“the author realizes this chapter is particularly strong and repulsive…He wishes he could have avoided writing that particular chapter”), entails being tortured to death. Although the imminent fingernail ripping, eyeball gouging and penis chopping are only described by Rafael’s would-be employers, those descriptions suffuse the remainder of the novel. Rafael, it transpires, is so unbelievably poor he lives in an abandoned motor home with his wife and three young children. With no hope of employment, the snuff film gig seems like a good idea, as it will bequeath a promised $30 grand to Rafael’s family. The central concept was intended primarily as a metaphor for the exploitation of the have-nots by the haves, but these days, with widespread poverty and the dominance of (so-called) reality television, the idea of a guy agreeing to sacrifice himself for money doesn’t seem at all farfetched.

4. THE GRIN OF THE DARK by RAMSEY CAMPBELL

With this novel the great Ramsey Campbell expertly mined the type of relentless, black-humored psychological dread that made his name. It’s the story of Tubby Thackery, a forgotten Fatty Arbuckle-esque silent film comedian, and one Simon Lester, a most unlucky film buff looking to write a book about Thackery’s career. Thackery, it seems, has made contact with a supernatural entity that uses his films to spread a malignant mind-virus–meaning Simon Lester is unwittingly doing just that. During his odyssey Simon gets into an online tiff with a pesky imdb message board poster, briefly stays in the home of a porno impresario who happens to be the granddaughter of Thackery’s stock director, and finds that Thackery’s face, with its perpetual grin, has a way of turning up everywhere. The book begins in relaxed and amiable fashion, but the tension steadily mounts, and all-but explodes during the final hundred or so pages, which, in some of the most unnerving prose Campbell has ever written, offer a minutely described reality breakdown that lingered long after I’d finished the book.

5. FLICKER by THEODORE ROSZAK

Perhaps the ultimate horrific fictional extrapolation on all things filmic. FLICKER tells the story of Jonathan Gates, a film nerd who provides an eminently readable first person recounting of his obsession with Max Castle, a long-forgotten German horror-meister. This is despite the fact that Gates finds Castle’s films, grade-z entertainments packed with sophisticated subliminal content, disturbing for reasons he can’t articulate. He learns that a renegade religious sect obsessed with the corrosive power of filmmaking, as represented by the flicker effect endemic to film projection that to them portends nothing less than the war between light and darkness, helped shape Castle’s aesthetic—and that this sect is still active. Unsurprisingly given that its author is best known for his nonfiction texts (Theodore Roszak actually penned the 1969 book that coined the term “Counterculture”), FLICKER functions in part as an eccentric tour through American film culture: the foreign film renaissance of the 1950s and 60s, the midnight movie craze of the 70s, the rise of film scholarship and the fortunes of the revival market are among the topics covered, all of them well integrated into the unfolding thriller narrative.

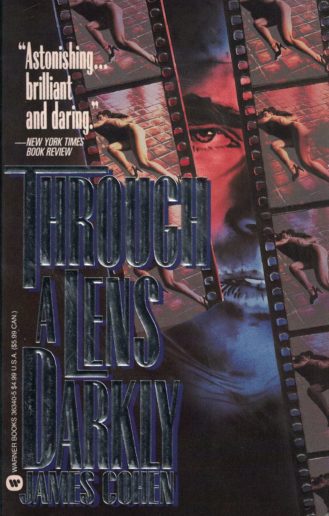

6. THROUGH A LENS DARKLY by JAMES COHEN

Chilling is a good term for this novel, as are twisted, disquieting and darkly prophetic. The setting is the lower rungs of Hollywood, as viewed by Chris, a film school graduate employed by a purveyor of death scene VHS compilations. Chris believes he’s found material for a promising documentary in video footage of a drowned girl’s final moments, wherein he spots an apparently psychotic glint in the eyes of her boyfriend. Chris tracks down the boy, one Todd Meacham, who lives with his parents in a sleepy Midwestern town. Passing himself off as a TV documentarian, Chris sets up cameras and sound equipment in and around the Meacham home, hoping to capture some real-life serial killer action. He ends up getting far more than he bargained for, as Todd Meacham is indeed a murderer—but so, it transpires, is his father William. I’ll halt the plot summary there and let prospective readers experience James Cohen’s ingeniously constructed narrative on their own. Those readers will find a realistic look at the darker edges of the dream factory that remains all-too topical.

7. SPLATTER: A CAUTIONARY TALE By DOUGLAS E. WINTER

This limited edition printing of Douglas E. Winter’s 1987 story “Splatter: A Cautionary Tale” includes an intro by Clive Barker (who rails against censorship in the US but never directly alludes to the story at hand) and a lengthy afterward by Michael A. Morrison. Winter’s tale offers a sophisticated exploration of censorship and madness centering on Rehnquist, a nut who has trouble distinguishing movie violence from reality. Orbiting him are Tallis, a writer of horror fiction under fire by the US government, and Cameron Blake, a feminist who blames all society’s ills on violent movies. The characters’ fates converge in the climax, wherein Rehnquist stages a phony suicide for Cameron and ends up lobotomized for his troubles. There’s much food for thought here, and enough stylistic flourishes to fill a full-length novel: the story is done in the style of J.G. Ballard’s THE ATROCITY EXHIBITION, taking the form of deliberately elusive paragraphs topped with bold-faced headings—26 in all, presented in alphabetical order—that consist of real-life horror movie titles: APOCALYPSE DOMANI, THE BEYOND, JUST BEFORE DAWN, VIDEODROME, etc. Plus, there are three surreal black and white illustrations by the incomparable J.K. Potter. It all adds up to a troubling look at some thorny real-life issues that offers no easy answers.

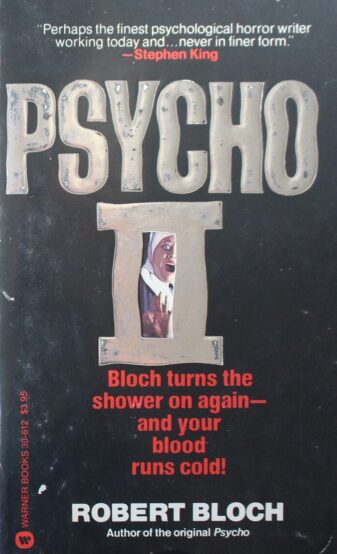

8. PSYCHO II by ROBERT BLOCH

This was the late Robert Bloch’s sequel to his 1959 novel PSYCHO, which of course inspired the Alfred Hitchcock film of the same name. This means the Norman Bates described here is different from the Anthony Perkins incarnated screen presence, and that this PSYCHO II, published in 1982, bears no relation to the PSYCHO 2 released to movie theaters in ‘83. Here Mr. Bates escapes from the insane asylum where he’s been interred since the events of the first PSYCHO by killing and impersonating a nun; he steals the nun’s van and heads off to, apparently, the filming of a movie dramatizing his crimes. From here on out the viewpoint shifts, with Norman exiting the picture and the film’s participants, who include an eccentric European director, a lead actor who takes his role a bit too seriously and Norman’s shrink Dr. Claiborne, taking center stage. All play a part in the ensuing hijinks, which involve arson, multiple murder and a banger of a twist. The drama is interspaced by frequent—too frequent—dissertations on movie violence versus reality, but Bloch knew how to craft an involving thriller, and in PSYCHO II he more than proved his mettle.

9. DIRECTOR’S CUT by CHAS. BALUN

Sadly, this 1995 novella was the final work of fiction by the late Chas. Balun. It’s a slight but robust 82-page work notable, as with Balun’s previous fictional works, for its lovingly described bloodletting. There is, however, an extra dimension to DIRECTOR’S CUT that showcases Balun’s maturation as a storyteller. It’s set in a horror nerd milieu of a type Balun knew extremely well, in a narrative involving filmmaker Jeff Rollins screening a director’s cut of his horror opus ZOMBIE BLOODBATH at the Director’s Guild Theater in Hollywood, with a bevy of journalists, businessmen and slavering fanboys in attendance. Also afoot is a psychopath looking to create his own real life horror epic, which he plans to orchestrate at the ZOMBIE BLOODBATH screening. DIRECTOR’S CUT can be viewed as Balun’s STARDUST MEMORIES or MISERY, i.e. a sharply critical rejoinder to his longtime fans and the subculture they inhabit, revealed here as a grimy gathering of socially deficient dimwits not entirely undeserving of the gruesome fates many of them meet.

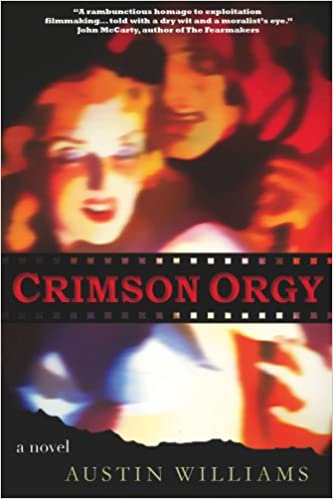

10. CRIMSON ORGY by AUSTIN WILLIAMS

As far as I’m aware, this is the only horror novel set in the world of 1960s-era exploitation moviemaking, the time and milieu of H.G. Lewis’ fabled proto-splatter classic BLOOD FEAST. The first novel by Austin Williams, CRIMSON ORGY has a suitably nerdy framework: it opens and closes with articles about an obscure 1960s splatter epic that allegedly contained footage of an actual killing. The filming of this opus takes place a couple years after BLOOD FEAST, and in the same South Florida locale, with director Sheldon Meyer and producer Gene Hoffman looking to outdo the excesses of Lewis’ film; the one-week shoot is best by a hurricane, a stolen film reel and a none-too-discreet affair between the leading actors. Austin Williams relates this twisted account with a great deal of slow-building suspense and convincing detail, and layers in discussions of the pressing real-life issues brought up by splatter films. In this way Williams provides a heartfelt tribute to exploitation movies of yore while simultaneously critiquing their anything-for-a-kick sensationalism. Some of the happenings, particularly those of the final pages, are horrifically gory, yet never seem the slightest bit implausible, which is perhaps the book’s most impressive feat.