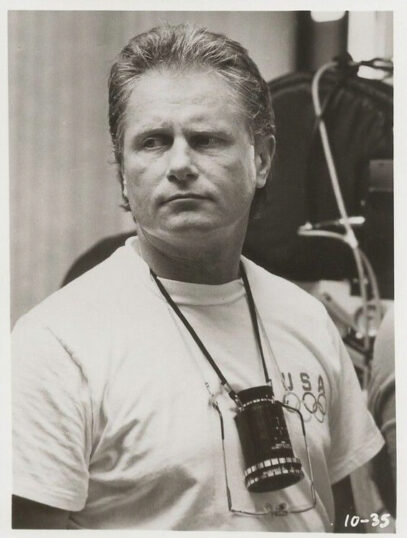

On February 15, 2025, one of America’s most individual, and least known, filmmakers left us. George Armitage was a screenwriter and director who labored in the Roger Corman exploitation factory alongside bigger names like Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Joe Dante and Armitage’s longtime pal Jonathan Demme. A self-described ex-hippie, Armitage was known for his nonaggressive attitude (according to Demme, “He’s not a hustler or a schmoozer, and that’s strike one and strike two”) and stubborn nature, having lost quite a few jobs by insisting on writing and directing his film projects.

As a director Armitage made two exceptional films, several “almost” movies and one outright misfire. He also scripted, but didn’t direct, two uniquely outrageous comedies that suggested a Ken Russell or John Waters-esque facility for outrage that was, unfortunately, never fully utilized.

Following a late 1960s stint as associate producer on PEYTON PLACE, Armitage began his filmmaking career in 1970 by scripting the Corman directed comedy GAS-S-S-S-S!—OR—IT BECAME NECESSARY TO DESTROY THE WORLD IN ORDER TO SAVE IT. It was Corman’s last directorial effort until FRANKENSTEIN UNBOUND twenty years later, as he was understandably upset with the heavy postproduction recutting perpetrated by AIP.

GAS-S-S-S-S! (1970) Trailer

Still, enough nuttiness survives to render GAS-S-S-S-S! a memorable time waster. The story? A gas escapes from a government laboratory that causes everyone over 25 to die, leaving us with a wasteland of late-60’s lunacy.

Armitage’s directorial debut was the Corman shepherded PRIVATE DUTY NURSES (1971), notable for its overt political leanings. In line with Armitage’s hippie orientation, there’s a great deal of pro-feminist and anti-racist messaging in addition to the requisite nudity and violence. The balance isn’t well maintained, as the sensational aspects are outweighed by the preachy ones, with the film ultimately coming off as quite dour.

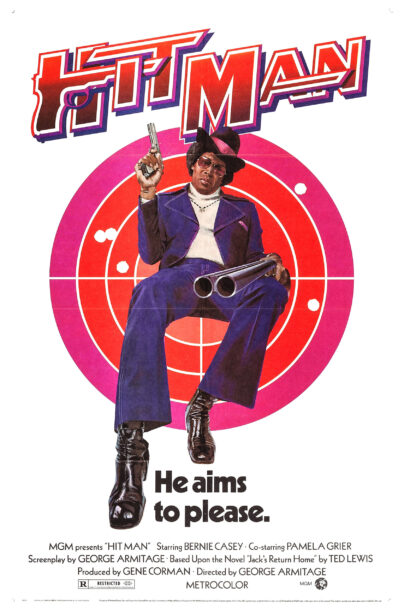

HIT MAN (1972) was a blaxploitation take on Ted Lewis’ classic British-centric crime novel JACK’S RETURN HOME, previously filmed as GET CARTER (1971). HIT MAN doesn’t measure up to that film, or the standout blaxploitation entries (such as SWEET SWEETBACK’S BAADASSSSS SONG and COFFY), but it contains some diverting violence, gratuitous nudity and the sight of a young Pam Grier being shut in a car trunk and savaged by a mountain lion. Plus, Bernie Casey is undeniably captivating in the main role.

HITMAN (1972) Trailer

Armitage’s next credit was as scripter of one of the wildest exploitation films of all time: the William Witney directed DARKTOWN STRUTTERS (1975). It was apparently conceived as a Mel Brooksian spoof of blaxploitation cinema, but what emerged is an anarchic exercise in Dadaesque absurdity.

The set-up involves four trike motorcycle riding black women based in LA, where they tangle with goofball cops who drive a police car topped by a giant red light, hyper-macho black men and a Colonel Sanders-esque rib magnate who resides in a mansion that closely resembles a southern plantation. Witney’s direction is serviceable, but Armitage’s script is quite something else, mixing cultural stereotypes (you can be sure that every racial caricature is touched upon) into a surreal swirl that’s funny, illuminating and often downright ugly.

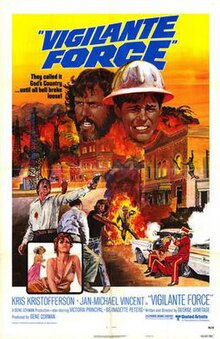

VIGILANTE FORCE (1976), Armitage’s premiere big studio outing, was an ill-advised venture. He wasn’t happy with the film or his direction of it, claiming his focus was on “Iconography instead of character,” i.e. scoring political points relating to the Bicentennial fever that swept the nation in ‘76 by (for instance) dressing the major antagonist in red, white and blue.

VIGILANTE FORCE (1976) Trailer

That said, for what it is VIGILANTE FORCE isn’t bad at all. It’s a bloody and diverting action-fest with a more thoughtful, character-based aesthetic than was standard for seventies actioners. Jan Michael-Vincent plays a small town resident and Kris Kristofferson his ‘Nam Vet brother, who answers Vincent’s call to help clean up the town, only to become fascistic and set up a new ruling class that itself needs to be overthrown.

The made-for-TV drag racing thriller HOT ROD (1979) isn’t great, but is stronger than similarly themed seventies-sploiters like DRAG RACER (1971) and FAST COMPANY (1979). Drag racing simply isn’t a very cinematic sport, of which Armitage seemed fully aware, creating a character-based drama with a strong central performance by Gregg Henry. He plays a loner arriving in a small town in what may be the 1950s to take part in a drag race, only to be harassed by a corrupt sheriff (Pernell Roberts) and a local tough (Grant Goodeve) whose wife (Robin Mattson) Henry is romancing. His exploits maintain viewer attention in time for the climax, in which Henry finally enters the desired hod rod competition. You’ll never guess who wins.

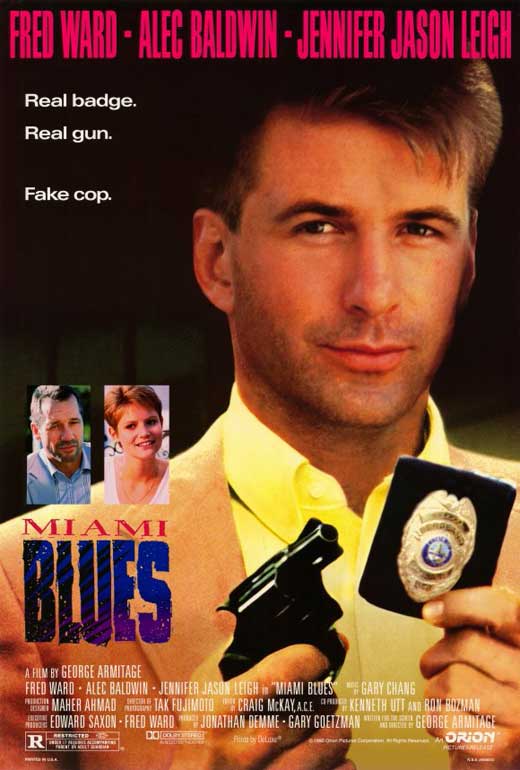

It took another eleven years for Armitage to direct another film. MIAMI BLUES (1990), adapted from Charles Willeford’s acclaimed 1984 crime novel, came about because of Demme, who found the property and produced the film. Yet the quirky and profane sensibility on display was pure Armitage, and the film overall his finest hour as director.

MIAMI BLUES (1990) Trailer

Alec Baldwin (then a hot up-and-comer) has never been better than he was playing the charismatic but hopelessly sociopathic Junior Frenger. Jennifer Jason Leigh all-but steals the show as Frenger’s airheaded hooker girlfriend, and Fred Ward shines as Sgt. Hoke Mosely, the gruff detective plagued by constantly disappearing false teeth. There are also fun appearances by Demme regular Charles Durning as Hoke’s former partner and Nora Dunn as his present one, Paul Gleason as a shifty cop and Shirley Stoler as a doomed pawn shop proprietor. Then there’s Armitage’s highly atmospheric portrayal of Miami, a dangerous yet curiously inviting beachfront environ.

Accomplished though MIAMI BLUES was, it had the effect of typing Armitage as a director of comedic crime sagas. The problem with that designation is a younger and more Hollywood-savvy director emerged in 1992 whose filmic orientation was similar—and who, unlike Armitage, made films that were financially successful. Said filmmaker, Quentin Tarantino, happens to be a big Armitage fan, which doesn’t appear to have done anything to enhance the Hollywood profile of the object of that adulation.

It took another seven years for Armitage’s subsequent directorial effort to arrive. In the meantime, he received screenplay credits on the 1990 feature THE LAST OF THE FINEST and the 1996 HBO telefilm THE LATE SHIFT. The former was an actioner upon which Armitage’s fingerprints were evident in the quirky narrative construction, which gives precedence to the title characters’ off-the-clock exploits with their wives and children. I had a hard time discerning Armitage’s touch in THE LATE SHIFT, a dramatization of the struggle for control of THE TONIGHT SHOW after Johnny Carson decided to step down in 1992; the proceedings aren’t nearly as outrageous as the filmmakers seem to believe they are given the opening disclaimer “Believe it or not, the following is based on truth…”

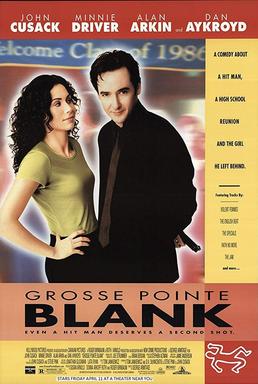

Fast forward to 1997, and the release of GROSSE POINTE BLANK, on which Armitage relaxed his traditional stance about writing and directing. Its basis was a spec script by Tom Jankiewicz that took several years to be sold, as its darkly comedic tone was apparently too subversive for Hollywood.

GROSSE POINT BLANK (1997) Trailer

Armitage proved the ideal interpreter of such tricky material, with MIAMI BLUES’ deft balancing of observational humor and violence repeated in a twisted account of a hitman (John Cusak) taking a job in his hometown of Grosse Pointe, MI, just as his ten year high school reunion is occurring. The juxtaposition of suburban mundanity and violence grows increasingly extreme, with Cusak reconnecting with an old girlfriend (Minnie Driver) while trying to follow through on the job at hand and fending off homicidal attacks by pissed off rivals.

The film had a rather large problem MIAMI BLUES didn’t: it followed RESERVOIR DOGS (1992) and PULP FICTION (1994), in whose wake GROSSE POINTE BLANK felt a mite derivative (Armitage acknowledged the similarity by placing a PULP FICTION standee in a convenience store shootout). That doesn’t change the fact that the performances are uniformly excellent, the quotable lines quite plentiful and Armitage’s ear for music, expressed on a soundtrack filled with many a classic rock tune, superb.

Continuing Armitage’s habit of undergoing lengthy lag times between features, his next directorial effort took until 2004 to arrive. THE BIG BOUNCE was an Elmore Leonard adaptation that followed the perimeters of most post-GET SHORTY (1995) Leonard filmings, which presented his funky, gritty narratives in comedic form. This of course was fully in keeping with Armitage’s post-MIAMI BLUES place in Hollywood, but by 2004 that aesthetic had worn thin.

The film vastly over-relies on the charisma of its star Owen Wilson and the pretty Hawaiian scenery (which lacks the atmosphere of MIAMI BLUES’ locations) to ferry us through a shockingly uneventful narrative involving Wilson as a con artist looking to make an especially lucrative score. It takes until the final twenty minutes for anything of any consequence to happen, a definite case of too little, too late. The problem may be that, as in GROSSE POINTE BLANK, Armitage didn’t write—or at least wasn’t credited with writing—the script. Another apparent problem is that the film, like GAS-S-S-S-S!, was subjected to heavy postproduction reediting, as is evident in the scant 88 minute runtime (at least 7 of which are taken up with end credits).

Unfortunately, THE BIG BOUNCE was Armitage’s last film credit. He spent his final years as he did much of the rest of his career: writing screenplays that were never filmed. He died, I understand, in Playa del Rey, an especially scenic portion of Southern California. Underappreciated George Armitage may have been, but at least he lived well.