It’s time for another trip back in time to the 1990s, when horror anthologies and David Lynch-inspired weirdness were mainstays of the comic book universe—for a time, at least. It’s an unfortunate fact that not everyone involved in the nineties comic book scene was able to properly navigate the constantly changing terrain of what was hip and what wasn’t. Case in point: writer-illustrator Al Columbia, a supremely gifted individual whose early—and, as it turned out, best—work was done in the 1990s but failed to catch the cultural zeitgeist, despite garnering a great deal of retrospective admiration.

It’s time for another trip back in time to the 1990s, when horror anthologies and David Lynch-inspired weirdness were mainstays of the comic book universe—for a time, at least. It’s an unfortunate fact that not everyone involved in the nineties comic book scene was able to properly navigate the constantly changing terrain of what was hip and what wasn’t. Case in point: writer-illustrator Al Columbia, a supremely gifted individual whose early—and, as it turned out, best—work was done in the 1990s but failed to catch the cultural zeitgeist, despite garnering a great deal of retrospective admiration.

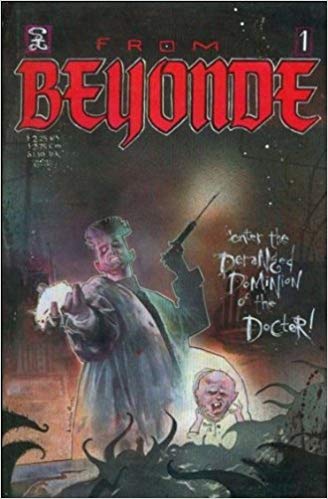

Columbia’s premiere entry in the underground comic book sphere was as the co-creator of the four-issue horror anthology series FROM BEYONDE, which debuted in February of 1991 and closed up shop in April of the following year. Anyone who knows anything about the horror boom that reached its apex in the preceding decade should be able to immediately spot the major problem here: horror, simply put, was declining in popularity in the early nineties. FROM BEYONDE, the first and only release of “Studio Insidio” and the “brainchild” of its main creator Mike Bliss, was Studio Insidio’s only release—a mighty unwise move, as it turned out, as the series underwent a tragic fate similar to those of the other horror anthology comics (MALFORMED, MASQUES, BONE SAW, etc.) that appeared around the same time.

Columbia had already received quite an education in comic book industry politics prior to FROM BEYONDE, having worked as an assistant on the legendary Alan Moore scripted, Bill Sienkiewicz illustrated disaster BIG NUMBERS (1990), a projected twelve part miniseries that imploded after just two issues. Note the acknowledgments page of FROM BEYONDE’S premiere issue, in which Columbia thanks Sienkiewicz for “a lifetime of learning and wisdom in roughly one year.”

That first issue started things off with striking cover artwork and interior illustrations by Columbia–here credited, for some reason, as “Lucien.” The opening story was  “You’re not Going to Kill this One…Are You Doctor?” a freakishly compelling, dark-humored tale of a genetics obsessed doctor and his hunchbacked assistant Boris, written by Mike Bliss and funkily illustrated by Frank Forte. Mad doctors were an evident obsession of Bliss and Forte, as they provide two more such stories, issue #2’s “The Connection,” written and illustrated by Forte, and “The Experiment” from #3, which hails once again from Bliss and Forte, and, with its arrestingly drafted images of a dissected corpse and a man being attacked by the intestines of said cadaver, can be decisively crowned FROM BEYONDE’S standout segment. Also quite striking is “Clara Mutilaires” from issue #2, a freeform five-parter involving murder, self-mutilation and a man-eating vagina that adequately showcases the originality and distinction of the inimitable Mr. Columbia, even at such an early stage of his career.

“You’re not Going to Kill this One…Are You Doctor?” a freakishly compelling, dark-humored tale of a genetics obsessed doctor and his hunchbacked assistant Boris, written by Mike Bliss and funkily illustrated by Frank Forte. Mad doctors were an evident obsession of Bliss and Forte, as they provide two more such stories, issue #2’s “The Connection,” written and illustrated by Forte, and “The Experiment” from #3, which hails once again from Bliss and Forte, and, with its arrestingly drafted images of a dissected corpse and a man being attacked by the intestines of said cadaver, can be decisively crowned FROM BEYONDE’S standout segment. Also quite striking is “Clara Mutilaires” from issue #2, a freeform five-parter involving murder, self-mutilation and a man-eating vagina that adequately showcases the originality and distinction of the inimitable Mr. Columbia, even at such an early stage of his career.

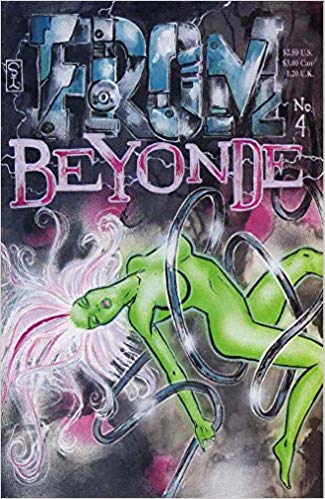

As to why FROM BEYONDE only lasted four issues, I believe the fact that the least of those issues happens to be its last had something to do with that. Columbia, for whatever reason, didn’t take part in issue #4, which is dominated, unfortunately enough, by “Positive Feedback,” a botched attempt at cyberpunk horror by Mark Wynne and Frank Forte that’s never too involving, nor even particularly well drawn. For what it’s worth, an issue #5 is teased on the final page that promises to feature a comic adaptation of Thomas Tessier’s story “Food” by Frank Forte, which does sound promising, and a potentially triumphant rebound from the crumminess of issue #4—but, alas, that just wasn’t to be.

There was, however, a rebound of sorts on the part of Al Columbia that same year. DOGHEAD, Columbia’s first solo comic endeavor, was an unashamed wallow in bizarrie that takes the form of three “pods” written and illustrated by Columbia. It shows the influence of Columbia’s mentors Bill Sienkiewicz and Dave McKean a bit too blatantly, but is worth tracking down, featuring as it does an impressive range of artistic styles that run the gamut from photo-realism to macabre distortion, often in a single panel.

There was, however, a rebound of sorts on the part of Al Columbia that same year. DOGHEAD, Columbia’s first solo comic endeavor, was an unashamed wallow in bizarrie that takes the form of three “pods” written and illustrated by Columbia. It shows the influence of Columbia’s mentors Bill Sienkiewicz and Dave McKean a bit too blatantly, but is worth tracking down, featuring as it does an impressive range of artistic styles that run the gamut from photo-realism to macabre distortion, often in a single panel.

The avant-garde storytelling is also quite distinctive, particularly in the first tale “Broken Face,” which intertwines an account of a featureless mask wearing man attempting to romance an outwardly elegant woman with a bevy of freaks lining up to ogle a peephole. Another stand-out is “Patio Lanterns,” a multi-faceted reverie involving tapeworms, a mutant baby, a talking fly, a game of Russian Roulette and a box with a button that when pressed will have some unknown result.

That latter subject is obviously quite similar to the set-up of Richard Matheson’s classic tale “Button, Button,” and that’s certainly not the only derivative element (the resemblance of a woman’s face in a couple panels to the ERASERHEAD baby is, I’m guessing, far from accidental). The final portion, entitled “Poster Child,” is notable as DOGHEAD’S only full-color segment, and almost entirely incoherent form a narrative standpoint, although the slip-streamy artwork is mesmerizing.

A third Al Columbia anthology project followed in 1994 and ‘95: THE BIOLOGIC SHOW, in which Columbia finally came into his own as one of the comic book world’s most unique purveyors of artistic dementia. It was once again over with far too quickly, lasting only two issues (with a third teased that, in a situation that had already become depressingly familiar to Columbia’s readers, never appeared). It seems THE BIOLOGIC SHOW had a problem with timing similar to that faced by FROM BEYONDE; just as that series mined outdated horror tropes, so did THE BIOLOGIC SHOW with David Lynchian weirdness,  something that by 1994 had fallen dramatically out of favor.

something that by 1994 had fallen dramatically out of favor.

The stories on display appear to have emerged directly from their creator’s subconscious. That realm is evidently a mighty dark place, yielding up depictions of biological mutation, dismemberment, a myriad of bizarre insectoid critters and much general ugliness, all tied together with a logic that’s strictly of the dreamlike variety. In this world penis-like “larval beings” float through the air, scattered viscera litters city streets, mutant fish grow in kids’ heads and people vomit up sperm-like critters that can fly. Yet as dark as all this is, there’s a ghoulish sense of Tim Burton-esque humor that wasn’t present in Columbia’s earlier works. Several characters that recur throughout Columbia’s art are introduced here, such as Seymour Sunshine, a freak with an inhumanly massive mouth, and Pim and Francie, a Pugsley and Wednesday Addams-esque brother-sister duo who can’t seem to keep from getting themselves into various surreal calamities.

THE BIOLOGIC SHOW, for the record, has grown in stature in the ensuing years. It’s attained the dubious distinction of having become a hipster celebrity accessory (Francis Bean Cobain reportedly has a Seymour Sunshine tattoo), and has apparently become extremely influential on modern comic book creators (from illustrator Aaron Horkey: “countless successful artists continue…propping up their half-baked careers on the well-worn spines of second hand copies of BIOLOGIC SHOW”). It’s just too bad we only got two issues of this peerlessly odd and disquieting series, and that Al Columbia largely fell off the map after it concluded.