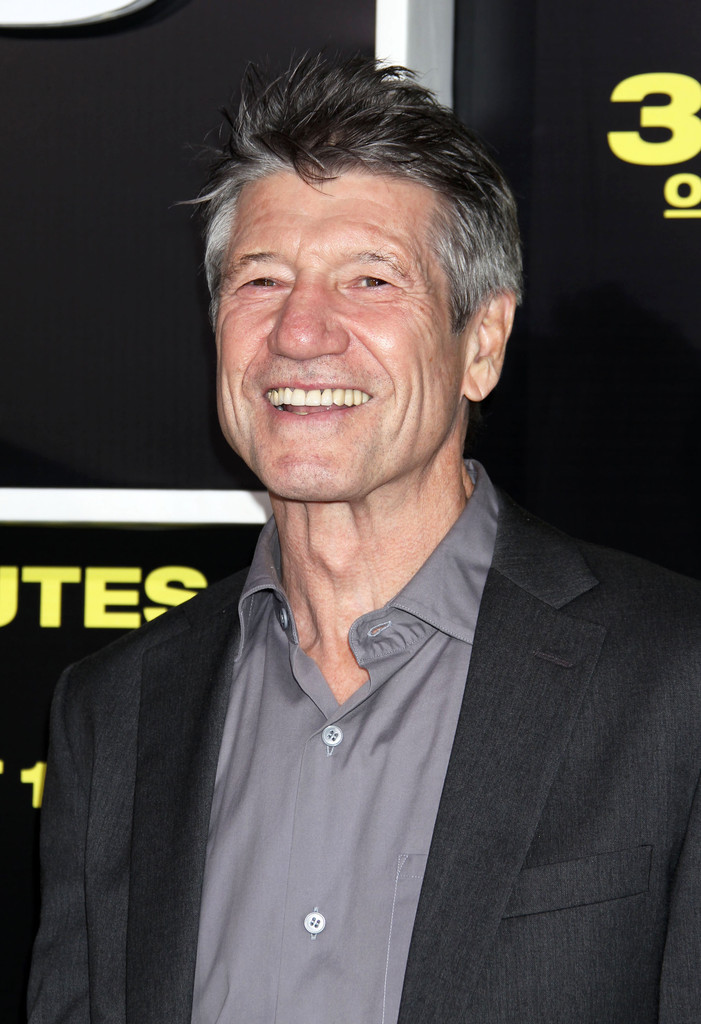

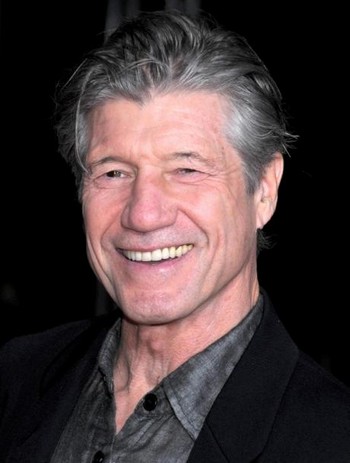

Actor Fred Ward, who died this week, had a staunch everyman vibe, yet he was also convincing as a tough guy. Those were qualities beloved by Hollywood in the eighties and nineties, and gave Ward a definite leg up during a period in which we were asked to believe Mel Gibson as a midwestern farmer in THE RIVER (1984) and Arnold Schwarzenegger as a construction worker in TOTAL RECALL (1990). Ward, I believe, would have been convincing in either role, just as he was in SHORT CUTS (1993), Robert Altman’s sprawling adaptation of several stories by the late Raymond Carver, transplanted from Carver’s native Pacific Northwest to the outskirts of Los Angeles.

If Altman’s irresistibly funky, freewheeling ramble of a film has an overriding flaw (aside from the fact that all its principals are white, which might have made sense in rural “Carver Country” but seems inexplicable in 90s-era LA), it’s that the cast is comprised entirely of movie stars (Tim Robbins, Robert Downey Jr., Madeleine Stowe, Julianne Moore, Matthew Modine, etc.) who aren’t entirely convincing as so-called ordinary folk. The exception is Ward, who in a narrative strand adapted from Carver’s tale “So Much Water So Close to Home” (which also provided the source material for the 2006 Australian film JINDABYNE) plays one of a quartet of working-class men on a fishing trip who after happening upon a woman’s drowned corpse elect to wait until after their expedition is done to alert the police, much to the consternation of Ward’s wife (a too beautiful-to-be-believed Anne Archer).

I greatly respect Fred Ward as an actor, but ultimately I like him for the same reasons I’m partial to Robert DeNiro: he graced quite a few of my favorite movies. For this reason, the following will be as much about Ward’s movies as the man himself.

I greatly respect Fred Ward as an actor, but ultimately I like him for the same reasons I’m partial to Robert DeNiro: he graced quite a few of my favorite movies.

I’d include SHORT CUTS on that favorite movies list, as well as Walter Hill’s SOUTHERN COMFORT (1981), made near the beginning of Fred Ward’s career. It followed small Ward roles in high profile films like the Donald Cammell scripted TILT, ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ (both 1979) and CARNY (1980). Ward’s turn in SOUTHERN COMFORT wasn’t much more auspicious than his previous ones, but like SHORT CUTS it amply demonstrates how well he embodied an everyman persona. In SOUTHERN COMFORT I’d say Ward fit in better with the overall atmosphere, in which national guardsmen are preyed upon by psychotic Cajuns in a superbly photographed bayou setting, than his starrier co-stars Keith Carradine and Peter Coyote.

What followed was a lead role in the ho-hum time travel western TIMERIDER: THE ADVENTURE OF LYLE SWAN (1982). It’s not much, but TIMERIDER was a film I recall viewing numerous times when it showed on cable in the 1980s. Ward’s turn in Jonathan Demme’s SWING SHIFT (1984) was a throwaway part, and the film itself a not-very-good Goldie Hawn vehicle that has gone on to become a veritable legend among film buffs due to the discovery of a supposedly much better workprint version. Having viewed that workprint, I can report that it is indeed superior to SWING SHIFT’S butchered release version, but don’t expect too much from it. The material was flawed to begin with, and not even Mr. Ward’s valiant efforts can save it.

The Tom Wolfe adapted THE RIGHT STUFF (1983) marked Ward’s “breakthrough” role. He played astronaut Gus Grissom, a fellow who (according to Wolfe) was undone by his own cockiness. Grissom is arguably the most nuanced and complex character in a film that views heroism, as the title indicates, in a somewhat less-than-complex manner—i.e. as in ingrown character trait one either has or doesn’t. As portrayed by Ward, Grissom muddies those waters somewhat, questioning the extent to which one’s character flaws might affect that “Right Stuff.”

REMO WILLIAMS: THE ADVENTURE BEGINS (1985) is not on my favorite movies list, although I say it’s unfairly underrated. A would-be blockbuster that was supposed to initiate a franchise, it was directed by James Bond regular Guy Hamilton and based on the DESTROYER series of men’s adventure novels by Warren Murphy and Richard Sapir, whose all-action approach Hamilton unexpectedly flipped. Certainly the film contains its share of violent action, but the best such sequence, set on and around the Statue of Liberty, occurs at the midway point, with the (supposedly) big logging camp-set climax being strictly so-so. The film’s major concern is with character development, and the relationship between the title character (Ward) and the Korean master (Joel Grey) who schools him in a supernatural fighting technique.

The fact that the latter is played by a heavily made-up Caucasian has long been controversial, but I say if we can accept white actors playing Hispanic characters, a practice that ran rampant in the eighties (SCARFACE, anyone?), then we can give REMO WILLIAMS a pass (while acknowledging that the filmmakers would probably have been better off, and saved themselves a lot of trouble, if only they’d hired an actual Korean). In the case of Fred Ward, at least, there’s no such conundrum: he played to his strengths, and also his race. It’s not his fault that the film as a whole wasn’t all it could have been.

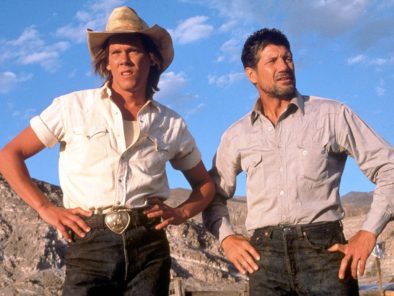

TREMORS (1990) is another nifty Ward vehicle. Radically different from the previous films in tone and style, it’s an enormously enjoyable, and largely misunderstood, monster movie. Far from the “so bad it’s good” spectacle that many insist on portraying it as, or the “intense horror movie” that others misidentify, it is in fact an overt comedy about giant worms terrorizing a desert community. The approach works far better than you might expect, with director Ron Underwood deftly balancing humor and action (though not necessarily horror) in a film that, to its credit, never pretends to be anything other than the lightweight fun machine it is. Ward once again puts his everyman air to good use, playing one of two rednecks (Kevin Bacon essays the other) who take it upon themselves to fight off the critters (for the record, Ward returned in 1996 for what turned out to be the first of several TREMORS sequels, none of which I’ve seen).

That in the case of MIAMI BLUES (1990) Ward not only starred in but also purchased the rights to the 1984 Charles Willeford novel upon which it was based shows that his talents stretched beyond acting. He was credited with executive producing the film, a violent and outrageous neo-noir pastiche that was nothing if not well staffed. The co-producer was the great Jonathan Demme at the height of his powers (he helmed SILENCE OF THE LAMBS around the same time), and the writer-director the nearly-as-gifted (though far less prolific) George Armitage, while the cast included imposing names like Jennifer Jason Leigh, THE HONEYMOON KILLERS’ Shirley Stoler and Alec Baldwin, who overshadowed Ward in the public eye with his turn as a charismatic but extremely dangerous sociopath (not exactly a stretch for Baldwin). I say Ward deserves equal credit for his turn as Hoke Moseley, the gruff detective tasked with taking down Baldwin; it’s a role that embodies all the characteristics conveyed in the novel (which inspired three Willeford drafted sequels, any one of which would make a terrific film).

I’m afraid I don’t have much good to say about HENRY AND JUNE (1990). Directed by Ward’s RIGHT STUFF collaborator Philip Kaufman, it made history as the first film to be rated NC-17 (and its box office failure assured that there haven’t been too many more). Ward, a last-minute replacement for Alec Baldwin, was rather severely miscast as Henry Miller, a character who wasn’t too in tune with Ward’s strengths as an actor (Baldwin was, frankly, a better choice). He was called upon to be a most unlikely sex symbol in a film that’s far too stately to be taken as an honest portrait of a man who once described his aesthetic as “a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art, a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty.”

Quentin Tarantino, at least, was an evident fan of the film, judging by the fact that his onetime place of employment, the fabled Video Archives, contained an imposing poster of Uma Thurman from HENRY AND JUNE on one of its walls, and that Tarantino cast Thurman and the film’s other leading lady Maria de Medeiros in PULP FICTION (1994). It seems odd that he never cast Ward in that or any of his other films, as he’d likely fit into Tarantino’s universe quite well (Tarantino is a known fan of ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ and CARNY, and has doubtless seen MIAMI BLUES).

Furthermore, Tarantino could have provided a boost to Ward’s career in the nineties. As it happened, his guiding influence in that era appears to have been Robert Altman. Ward’s film choices then tended to be of the independent variety: Altman’s overrated THE PLAYER, EQUINOX (both 1992), TWO SMALL BODIES (1993) and, most interestingly, BOB ROBERTS (1992). The latter, a political satire by writer-director-star Tim Robbins, is an entertaining screed that’s more interesting for what it attempts than what it accomplishes (for an object lesson in how that attempt might have panned out, see Altman’s brilliant made-for-cable mock-documentary TANNER ’88).

Things bottomed out completely in the aughts, which saw Fred Ward relegated to “Dad” roles in bummers like JOE DIRT (2001), ENOUGH and SWEET HOME ALABAMA (both 2002). Mom and Dad roles are an increasing inevitability for aging actors, and despite some recent successes (Marisa Tomei has been nearly as successful playing moms as she was as a nineties ingenue) usually mark the end of a career. That was certainly the case with Ward, whose final credit, on the long running series TRUE DETECTIVE, was in 2015. Quite simply: he deserved better.