Here we’re confronted with an issue that increasingly demands we take a side. Remember last December, when Quentin Tarantino’s HATEFUL EIGHT was released to great fanfare in a 70mm roadshow version? You may also recall the pontificating by Tarantino about the primacy of celluloid over digital cinema (as well as a lot of kvetching that the film never got to play in its intended venue, Hollywood’s fabled Cinerama Dome). I’d argue that THE HATEFUL EIGHT’s cinematic merits got lost amid all the proselytizing, but no matter: in so forcibly promoting filmic exhibition Tarantino galvanized a debate that has been brewing for years.

Here we’re confronted with an issue that increasingly demands we take a side. Remember last December, when Quentin Tarantino’s HATEFUL EIGHT was released to great fanfare in a 70mm roadshow version? You may also recall the pontificating by Tarantino about the primacy of celluloid over digital cinema (as well as a lot of kvetching that the film never got to play in its intended venue, Hollywood’s fabled Cinerama Dome). I’d argue that THE HATEFUL EIGHT’s cinematic merits got lost amid all the proselytizing, but no matter: in so forcibly promoting filmic exhibition Tarantino galvanized a debate that has been brewing for years.

Horror fans are an integral part of this debate whether we like it or not, as horror cinema has arguably done more to popularize the digital format than any other type of film. Consider: it was the horror sphere that made video, the forerunner of digital, a viable format in the late eighties and early nineties (in camcorder lensed features like DARK ROMANCES, SAURIANS, SHATTER DEAD, etc). The horror genre also provided the world’s first-ever digitally filmed (1997’s LOVE GOD) and exhibited (1998’s THE LAST SCREENING) features. It’s certainly no accident that genre filmmakers embraced digital so enthusiastically, given that horror tends to thrive in low budget format, and digital is nothing if not budget-friendly (it doesn’t require complicated lighting set-ups or cumbersome cameras). But is it truly the end-all format it’s been cracked up to be?

Here I find myself flashing back to the glory days of Showscan, a format introduced in the late seventies. Developed by special effects  legend Douglas Trumbull, Showscan showed films at 60 frames a second rather than the standard 24, and was once proclaimed the wave of the future in theatrical exhibition. Back in the eighties I got to experience Showscan numerous times at its (now shuttered) Culver City headquarters, courtesy of my dad, who scripted a short film designed to promote the format (the Trumbull directed LEONARDO’S DREAM). To this day Showscan’s visuals remain the clearest, most eye-poppingly vivid I’ve ever seen in a theater.

legend Douglas Trumbull, Showscan showed films at 60 frames a second rather than the standard 24, and was once proclaimed the wave of the future in theatrical exhibition. Back in the eighties I got to experience Showscan numerous times at its (now shuttered) Culver City headquarters, courtesy of my dad, who scripted a short film designed to promote the format (the Trumbull directed LEONARDO’S DREAM). To this day Showscan’s visuals remain the clearest, most eye-poppingly vivid I’ve ever seen in a theater.

Why then did Showscan never catch on outside the ride-film (or 4D) arena? For starters it was expensive, requiring specially outfitted cameras and projectors. Plus, viewing Showscan wasn’t nearly as pleasurable as it might sound, given that it’s the mind that ultimately creates the illusion of movement amid the twenty four frames a second of normal film—thus with Showscan one’s brain had to work nearly three times as hard. This explains why I emerged from every Showscan screening with a raging headache, and ultimately had no problem returning to traditional movie exhibition (although I’ll admit I’ve never quite viewed it in quite the same way as I did before; it wasn’t until after experiencing Showscan that I became aware of just how flickery traditional film projection really is).

Fast forward to 2016, when we’re faced with another alternative movie format. Obviously there are plenty of differences between Showscan and digital cinema, not least the fact that digital is hardly the flash in the pan Showscan was. Far from it, in fact: as quoted in a 2012 L.A. Weekly article on the subject, National Association of Theater Owners president John Fithian made the point that “If you (movie theater owners) don’t make the decision to get on the digital train soon, you will be making the decision to get out of the business.” Yes, in a bid to save money Hollywood has forced digital projection upon first run and revival theaters alike, despite the fact that, like Showscan, digital cinema is not without some very real problems.

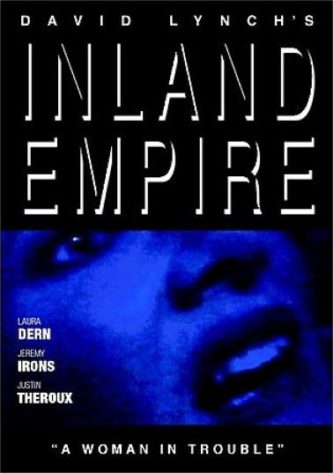

If the Hollywood studios are in love with digital cinema, it seems quite a few prominent filmmakers are just as partial. I can recall William Friedkin at a Pasadena Fangoria convention singing the praises of digital exhibition while promoting the 2000 reissue of THE EXORCIST. David Lynch was similarly besotted, claiming after 2006’s digitally lensed INLAND EMPIRE that he was done with film—never mind that INLAND EMPIRE, while quite pictorially striking in its way, is the least visually resonant of Lynch’s films. INLAND EMPIRE does at least look better than early-00s indies like PIECES OF APRIL, CHUCK & BUCK, IVANSXTC and BAMBOOZLED, all of which were digitally shot and then transferred to 35mm, resulting in washed-out, vomit-tinged visuals those film’s directors evidently overlooked in their excitement about this new and inexpensive format.

If the Hollywood studios are in love with digital cinema, it seems quite a few prominent filmmakers are just as partial. I can recall William Friedkin at a Pasadena Fangoria convention singing the praises of digital exhibition while promoting the 2000 reissue of THE EXORCIST. David Lynch was similarly besotted, claiming after 2006’s digitally lensed INLAND EMPIRE that he was done with film—never mind that INLAND EMPIRE, while quite pictorially striking in its way, is the least visually resonant of Lynch’s films. INLAND EMPIRE does at least look better than early-00s indies like PIECES OF APRIL, CHUCK & BUCK, IVANSXTC and BAMBOOZLED, all of which were digitally shot and then transferred to 35mm, resulting in washed-out, vomit-tinged visuals those film’s directors evidently overlooked in their excitement about this new and inexpensive format.

Now that digital projection has come into vogue the 35mm transfer issue is no longer a factor, resulting in visuals that look a lot better. This, however, presents an even greater problem: the clarity of digital projection makes it impossible to hide or obscure the makeup on actors’ faces (a problem, I recall, that plagued Showscan as well), nor the bad acting of said performers, whose true commitment to a role is evident in a way it never was in filmic form.

Furthermore, I found that upon viewing the celluloid roadshow version of THE HATEFUL EIGHT I actually appreciated the grit and scratches endemic to film. Taking a cue from vinyl enthusiasts who claim the format’s greatness is precisely because it’s such a pain in the ass to store and take care of, it could be argued that film’s primary appeal is its unwieldiness and fragility. A film print is bulky, takes up a lot of space and demands the utmost care on the part of its handlers, all of which I learned during my early nineties stint as a projectionist at a So Cal multiplex, when film breaks and scratches were daily occurrences. To me the idea of projection without those things seems out of place and plain wrong.

In fairness, digital cinema has plenty of advantages (aside from those of convenience). I can’t imagine digitally shot masterworks like Tomas Winterberg’s Danish outrage THE CELEBRATION, Robert Rodriguez’s depraved comic book pastiche SIN CITY or Shahram Mokri’s Iranian made one take-wonder FISH & CAT presented in any other format, which was key to those films’ innovative brilliance. So I acknowledge that digital has a place in the movie world, and a vital one, but film is and always will be my preferred medium, regardless of how much Hollywood tries to convince me otherwise.