August 9, 2019 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the murders committed by the Manson family. This was an event many claim put a decisive end to the idealism of the 1960s and the carefree hippie ethos, ushering in a new era of fear and suspicion. Something else it ushered in was a never-ending stream of “Mansonsploitation” media.

August 9, 2019 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the murders committed by the Manson family. This was an event many claim put a decisive end to the idealism of the 1960s and the carefree hippie ethos, ushering in a new era of fear and suspicion. Something else it ushered in was a never-ending stream of “Mansonsploitation” media.

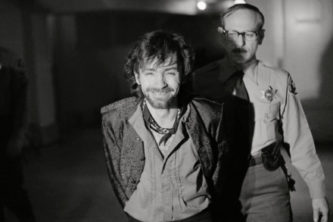

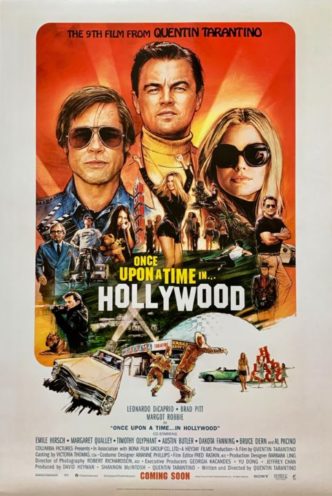

A quick refresher: the Manson “family” refers to followers of the late cultist Charles Manson (1934-2017), who at the time of the killings were residing at the Los Angeles based Spahn Movie Ranch. The family’s August ‘69 victims were actress Sharon Tate, the pregnant wife of Roman Polanski (who was out of the country), and her companions as part of a series of Manson-ordered murders that came to include supermarket executive Leo LaBianca and his wife Rosemary. Manson, who was arrested in August of ‘69 and spent the remainder of his life incarcerated, naturally went on to become something of a pop culture celebrity, a figure that according to late Adam Parfrey was “transmogrified by the electronic thaumaturgy of mass media into a mythic creation, a larger-than-life hieratic emblem of evil.” Among that media is Quentin Tarantino’s ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD, released on July 26, 2019 to a fair amount of success, and not a little controversy.

That controversy has been multi-pronged, encompassing the film’s portrayal of Bruce Lee, the lack of dialogue given to Margot Robbie as Sharon Tate and, most importantly for the purposes of this article, the “exploitive” portrayal of Manson and his followers. Tarantino has done his best to deflect the charges, admitting that portraying the Manson family possibly “falls into bad taste” and that “I had to earn the right to do it at some point in the material…If I’d tried it and wasn’t able to pull it off, then I wouldn’t have made the movie.” I’m not sure I entirely buy that justification, as Tarantino is an enthusiastic  student of cinema du exploitation, and was undoubtedly aware of the vast history of Mansonsploitation movies, TV specials and fiction, into which ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD fits quite well.

student of cinema du exploitation, and was undoubtedly aware of the vast history of Mansonsploitation movies, TV specials and fiction, into which ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD fits quite well.

Why the inexhaustible fascination with Charles Manson and his crimes? The fact that the details of the killings (which I won’t go into here) are among the most gruesome in American history probably has some bearing on the continuing popularity of the Manson saga, and also the fact that it involved wealthy Hollywood figures, which is something that has always fascinated America—especially when murder is involved.

A recent Variety article decried the “many tasteless depictions of the killings via low-budget exploitation films and TV offerings.” Sharon Tate’s sister Debra was even more irate, claiming in a 2018 essay that “Members of the Manson family have left a permanent stain on our culture. The entertainment industry has helped them reach almost mythic status by churning out seemingly never-ending anniversary shows, recordings of Manson’s music, books, television programs, movies and documentaries.”

Debra Tate’s admonition about Manson-inspired music is reflected in the fact that Manson was a failed musician with ties to Neil Young and Brian Wilson—and is believed to have ordered the Tate killings because his bid for a recording contract had been turned down by the record producer Terry Melcher, the previous tenant of the Cielo Drive house where Tate was living on 8/9/69. Manson’s influence on the music scene is too varied to go into here outside two prominent examples: a young Henry Rollins corresponding with and producing a never-released album with Manson, and Trent Reznor setting up a recording studio in the Cielo Drive mansion where Sharon Tate was murdered. The musicians in both cases later repented, with Rollins admitting “At the time I was very young, and having him write letters to me made me feel intense and heavy” and Reznor (after being confronted by Debra Tate) concluding that “I don’t want to be looked at as a guy who supports serial-killer bullshit.”

Onto the documentaries Debra Tate mentioned. MANSON, the first and best of them, hailed from 1973, and was followed in 2007 by the vastly inferior INSIDE THE MANSON GANG, comprised of outtakes from the earlier film. Further docos of interest include the outrageous Nikolas Schreck directed pro-Manson screed CHARLES MANSON SUPERSTAR (1989), THE SIX DEGREES OF HELTER SKETLER (2009), OLD MAN, a short film depicting Manson in his later years, and LIFE AFTER MANSON (2014). The Rob Zombie narrated CHARLES MANSON: THE FINAL WORDS, from 2017, tries to make the case that the charges against Manson were unjust, while CHARLES MANSON: THE FUNERAL documents Manson’s funeral and in MANSON: THE WOMEN four of his female family members give their thoughts on his crimes—all three films, as you might guess given the uniformity of their titles,  were directed by the same guy, the TV documentary specialist James Buddy Day.

were directed by the same guy, the TV documentary specialist James Buddy Day.

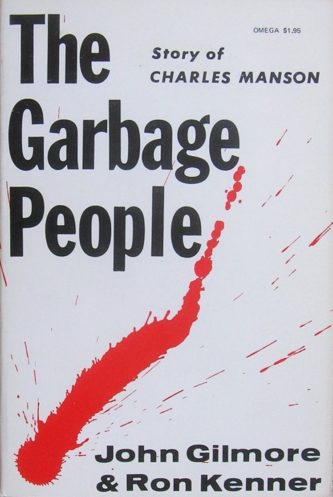

Nonfiction books about Manson, the family and the effect of their crimes upon the American psyche have been myriad, starting in 1970 with THE KILLING OF SHARON TATE, a quickie publication by Jerry Cohen and Dial Torgerson. 1971 saw the printing of THE GARBAGE PEOPLE (or, as it’s been retitled, MANSON) by John Gilmore and Ron Kenner, which has gone on to become a standard reference work for the Manson-obsessed. Even more iconic was THE FAMILY by Ed Sanders, a counterculture-infused study that likewise appeared in 1971. 1973 marked the release of HELTER SKELTER by Vincent Bugliosi—who prosecuted Manson—and Curt Gentry, which has become the standard reference book about Manson and the bestselling true crime book of all time. And we mustn’t forget THE WHITE ALBUM, a 1979 nonfiction anthology by Joan Didion that contained the eponymous essay, in which she ruminates at some length on the Manson killings, having directly involved herself in them through Linda Kasabian, the lead witness in the case, for whom Didion purchased a dress Kasabian wore to court.

More recent nonfiction texts include 1977’s CHILD OF SATAN, CHILD OF GOD by ex-Manson follower Susan Atkins, the first of innumerable memoirs by figures connected with the Manson family, the most recent being 2017’s MEMBER OF THE FAMILY by Dianne Lake. In 1984’s ROMAN a certain Mr. Polanski gave his own take on the Manson murders, although the vast majority of the book focuses on another, more recent crime (the particulars of which I’m sure we’re all at least partially aware). MANSON: IN HIS OWN WORDS appeared in 1987, with Manson airing his opinion about its contents via a copy of the book sent to a fan in which he inscribed “Bullshit,” along with a pair of soiled underpants. The 1988 Amok Press anthology THE MANSON FILE, credited to Manson enthusiast Nikolas Schreck (the actual author/editor was apparently Adam Parfrey), took a decidedly pro-Manson tack, trying—and failing—to make the argument that Manson was (as Schreck proclaimed on a mid-eighties episode of Wally George’s HOT SEAT) “one of the great philosophers of our age.”

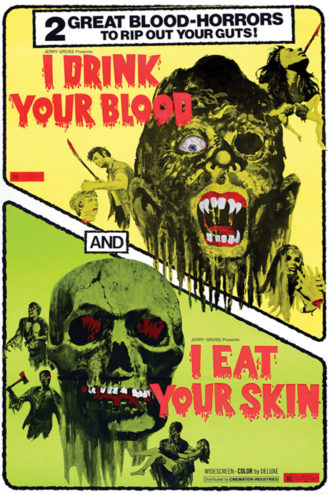

Then we have Manson-inspired cinema, in which the “sploitation” angle was multiplied exponentially. One of the very first Mansonsploitation films out of  the gate (not counting past films that were re-released to capitalize on the crimes, such as 1969’s ANGEL, ANGEL, DOWN WE GO, which was reissued as CULT OF THE DAMNED, and SATAN’S SADISTS, initially released a few weeks prior to the Tate killings and later billed as “The REAL story” of the “Sadistic Tate Murder Hippie Cult”) was 1970’s I DRINK YOUR BLOOD. It combined an account of a Manson-esque hippie cult with a NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD inspired narrative that sees the hippies, led by the late painter-dancer Bhaskar Roy Chowdhury, infected with rabies. The resulting mayhem spree doesn’t offer much insight into the Bhaskar’s real-life inspiration, but as pure rotgut entertainment it satisfies, being, as it turned out, the highpoint of Mansonsploitation moviemaking (at least until Quentin Tarantino got involved).

the gate (not counting past films that were re-released to capitalize on the crimes, such as 1969’s ANGEL, ANGEL, DOWN WE GO, which was reissued as CULT OF THE DAMNED, and SATAN’S SADISTS, initially released a few weeks prior to the Tate killings and later billed as “The REAL story” of the “Sadistic Tate Murder Hippie Cult”) was 1970’s I DRINK YOUR BLOOD. It combined an account of a Manson-esque hippie cult with a NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD inspired narrative that sees the hippies, led by the late painter-dancer Bhaskar Roy Chowdhury, infected with rabies. The resulting mayhem spree doesn’t offer much insight into the Bhaskar’s real-life inspiration, but as pure rotgut entertainment it satisfies, being, as it turned out, the highpoint of Mansonsploitation moviemaking (at least until Quentin Tarantino got involved).

THE MANSON MASSACRE, released to the trash movie circuit in 1971, is a plodding bust, notable only for its portrayal of “Manson” as a robed figure with God-like powers. In reality Manson was short and wiry, but the film world, and the media overall, seemed quite taken with the Rasputin-like personage unveiled in THE MANSON MASSACRE. Just check out the same year’s OTHER SIDE OF MADNESS (retitled THE HELTER SKELTER MURDERS), a black and white no-budgeter that likewise portrays a stern and imperious Manson, and likewise suffers from a dreary and heavily padded treatment—although some effort was clearly put into the dramatization of the Tate killings, which are unnervingly recreated. There was also SWEET SAVIOR, a.k.a. THE LOVE THRILL MURDERS, featuring ex-Hollywood heartthrob Troy Donahue as a Manson stand-in who appears to have been equally inspired by the Church of Satan’s late founder Anton LaVey. The film, in any event, is a non-starter, as is 1972’s THE DEATHMASTER, whose cult leader antagonist (Robert Quarry) was a vampire delivered via coffin to a Spahn Ranch stand-in in the back of a pickup truck.

There was a definite schism in the Manson-inspired cinema of the early 1970s, with the abovementioned films taking the killers’ POVs. In the other category were equally scrappy efforts like THE NIGHT GOD SCREAMED (1971) and TERROR ON THE BEACH (1973), related from comfy middle class standpoints invaded by murderous hippie cults. In the listless NIGHT GOD SCREAMED the protagonists are a religious couple, the male half of which is crucified by the hippies, leaving his traumatized widow to take on the scumbags by herself in the STRAW DOGS-lite climax. The made-for-TV TERROR ON THE BEACH, about a suburban family terrorized by dune buggy riding longhairs while on a camping trip, is only slightly better. Ultimately those films stood as mere run-ups to the ultimate middle class reaction to the Manson murders: the small screen adaptation of HELTER SKELTER.

This two part miniseries was broadcast in April of 1976. A just-the-facts-ma’am dramatization of Vincent Bugliosi’s bestseller, it suffers from a studiedly unadventurous, nuance-free treatment, and is overlong to boot. The performance of Steve Railsback, however, stands as the finest and most accurate Manson impersonation to date, pulled off with a hyperactive intensity that stands in stark contrast to the overly imperious movie Mansons of the first half  of the decade. HELTER SKELTER was remade in 2004, with Jeremy Davies as Manson, and, surprisingly enough, wasn’t bad, focusing more on the family itself than Bugliosi’s investigation into it, although it lacks the bone-chilling charge Railsback brought to the original.

of the decade. HELTER SKELTER was remade in 2004, with Jeremy Davies as Manson, and, surprisingly enough, wasn’t bad, focusing more on the family itself than Bugliosi’s investigation into it, although it lacks the bone-chilling charge Railsback brought to the original.

The fiction market, you can be sure, had its own share of exploitive Manson cash-ins. The 1970 paperback THE HIPPY CULT MURDERS by Ray Stanley, about a loony cultist who “could easily pass for Jesus Christ” gathering together a “family” of nubile young women on the orders of an all-powerful deity known as Zember, was one of the first such books, and was every bit as sleazy and disreputable as any trash fiction fan could possibly desire. What it’s not is particularly exciting or audacious, being disappointingly conventional in its structure and arc, especially in light of the fact that the Manson case happens to be one of the most bizarre in American history.

Far stronger is the 1971 comic book one-shot THE LEGION OF CHARLIES by Tom Veitch, Greg Irons and Dave Sheridan. It’s been called the greatest underground comic of all time, which I feel is a bit excessive, but it does pack a definite punch. The subject is “Kali” (a.k.a. Mai Lai orchestrator William Calley), who is summoned by the spirit of “Charlie” (as in Charlie Manson) to a gathering of acolytes that leads to a worldwide orgy of murder and cannibalism. As satire the whole thing is overly ham-fisted, yet it has a fire and ferocity unusual in underground comics (which even at their most political tend to be aloof and disaffected).

SWEET EVIL by Charles Platt was published in 1977, with a cover promising a “Helter-Skelter Hellride of Erotic Violence.” It was actually drafted in the early 1970s for the fuck book outfit Olympia, only to be orphaned after Olympia went belly-up. It concerns a young hitchhiker who meets up with a free-spirited woman, each of whom inspire dark desires in the other, thus initiating a twisted odyssey of perversion with numerous references to the Manson  murders, including the presence of a murderous cult. The same year saw the bow of BLIND DATE by the late Jerzy Kosinski. Kosinski, a longtime Roman Polanski acquaintance, used BLIND DATE to dramatize a (widely disbelieved) story he liked to tell about how he was in route to the Polanski-Tate Cielo Drive residence on August 9, 1969, only to be waylaid in NYC. The disturbed narrator of BLIND DATE experiences just such a snafu, and writes of having his pals slaughtered in a manner that closely paralleled that of the real Sharon Tate murders.

murders, including the presence of a murderous cult. The same year saw the bow of BLIND DATE by the late Jerzy Kosinski. Kosinski, a longtime Roman Polanski acquaintance, used BLIND DATE to dramatize a (widely disbelieved) story he liked to tell about how he was in route to the Polanski-Tate Cielo Drive residence on August 9, 1969, only to be waylaid in NYC. The disturbed narrator of BLIND DATE experiences just such a snafu, and writes of having his pals slaughtered in a manner that closely paralleled that of the real Sharon Tate murders.

The 1980s saw no halt to Manson inspired novels and films. J.G. Ballard’s HELLO AMERICA, from 1981, was a quasi-satiric portrait of an uninhabitable future America ruled by a lunatic who proclaims himself “President Charles Manson.” 1984 saw the bow of John Aes-Nihil’s MANSON HOME MOVIES, a (supposedly) painstaking attempt at recreating the home movies the Manson family is alleged to have filmed with stolen broadcast equipment. The results, alas, are unconvincing, despite having been filmed in the actual locations where the Manson family resided. The problem is the performers don’t resemble the real life personages they’re supposed to be portraying (with several of the women clearly played by men), and in any event aren’t very skilled thespians.

Another budget-lite Manson themed film, the Troma production IGOR AND THE LUNATICS, appeared the following year. It added a strong dose of eighties gloss to the Mansonsploitation movies of the previous decade (in the form of a beyond-dated synthesizer score and cinematography that seems better suited to a perfume commercial), but otherwise has very little to offer outside yet another gang of bloodthirsty hippies led by yet another charismatic lunatic—this particular lunatic, FYI, resides in a forest compound and likes to slice women up with a table saw.

Also hailing from 1985 was the endearingly ridiculous THOU SHALT NOT KILL…EXCEPT. It’s a straightforward kill-fest involving a cadre of ‘Nam vets going up against a (by now familiar) hippie cult led by an (equally familiar) shaggy-haired spaz—who’s played, unlikely enough, by EVIL DEAD director Sam Raimi. The film is what you might expect given director Josh Becker’s strapped budget and Raimi’s limited acting skills, although it is enjoyable on a braindead RAMBO-esque level (appropriately enough, the similarly minded RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II was released the same year).

The late 1980s were an especially fertile period for Manson mania. It was in 1986 that an Emmy award winning Charlie Rose interview with Manson aired on NIGHTWATCH, and two years later that an even more iconic Manson TV interview appeared, this one conducted by Gerald Rivera and aired during primetime (and allegedly inspiring a young Quentin Tarantino to give the screenplay for his BADLANDS pastiche NATURAL BORN KILLERS a media-centric overlay).

The late 1980s were an especially fertile period for Manson mania. It was in 1986 that an Emmy award winning Charlie Rose interview with Manson aired on NIGHTWATCH, and two years later that an even more iconic Manson TV interview appeared, this one conducted by Gerald Rivera and aired during primetime (and allegedly inspiring a young Quentin Tarantino to give the screenplay for his BADLANDS pastiche NATURAL BORN KILLERS a media-centric overlay).

A shot-on–video feature appeared in 1989 entitled THE BOOK OF MANSON, lensed in Hermosa Beach, CA by the artist Raymond Pettibon (one of several Pettibon helmed SOV films from that year centering on infamous American figures—others include CITIZEN TANIA, about Patty Hearst, and WEATHERMAN ‘96, about the Weather Underground). Quite simply put: it’s not much.

The trend of cash-strapped Manson-themed indies reached its apex, arguably, with THE MANSON FAMILY. It began in 1988, when filmmaker Jim VanBebber, of the no-budget wonder DEADBEAT AT DAWN (1988), began production on a feature entitled CULT KILLER. It took fifteen years for the film, retitled CHARLIE’S FAMILY and then THE MANSON FAMILY, to reach completion, during which time VanBebber worked at a Wendy’s to make ends meet, made two short films and spent time in jail. Anticipation for the film, meanwhile, reached a fever pitch among horror and cult film buffs, with  the screenplay published by Creation Books in 1998 and a 16mm promo reel making the rounds of the greymarket circuit around the same time. It would be nice to say the finished film, theatrically released in 2004, was the unqualified triumph so many of us were hoping for, but its ultra-low budget treatment, evident in the performances and production values, cripples VanBebber’s lofty ambitions.

the screenplay published by Creation Books in 1998 and a 16mm promo reel making the rounds of the greymarket circuit around the same time. It would be nice to say the finished film, theatrically released in 2004, was the unqualified triumph so many of us were hoping for, but its ultra-low budget treatment, evident in the performances and production values, cripples VanBebber’s lofty ambitions.

At least, in its pitiless portrayal of the drugged-out states of the Manson family members, THE MANSON FAMILY had the right spirit. That alone places it far ahead of LESLIE, MY NAME IS EVIL, a 2009 Canadian production—retitled MANSON, MY NAME IS EVIL—that likewise offers a budget-lite exploration of the family’s dynamics. It focuses on the murder trial of Manson family member Leslie van Houten (Kristen Hager), but is done in by hopelessly unconvincing period detail, clumsy performances and an uncertain, vaguely satiric tone.

The inauthenticity of LESLIE, MY NAME IS EVIL suggests that, simply, the Manson killings may just be too far in the past to be effectively dramatized, even in a fanciful or comedic manner. Fanciful and comedic certainly describe the 2006 cult item LIVE FREAKY! DIE FREAKY!, which sarcastically recreates the events of August of ‘69 via puppet and Claymation depictions of Manson, his followers and Sharon Tate. Like many a cult item then and now, this film clearly thinks it’s the hippest, most transgressive thing around, with voice-overs by the cooler-than-thou likes of Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong, Asia Argento, Kelly Osbourne and a host of punk rock figures. It’s almost certainly the most exploitive of the Manson-inspired media, presenting the whole saga as a quasi-pornographic goof with a sense of humor that falls on the middle school level, and ultimately resembling nothing so much as the infamous puppet porno feature LET MY PUPPETS COME (1976). The fact that so much time had passed since the actual events it depicts explains, perhaps, why LIVE FREAKY! DIE FREAKY! didn’t inspire much outrage.

The passage of time would also appear to explain the phenomenon of the post-millennium Manson novels that have garnered great acclaim. Apparently it’s okay now to consume Manson-inspired media, so long as it’s presented with a literary overlay. See THE DEAD CIRCUS by John Kaye, a self-consciously noirish exploration of Manson’s legacy, and THE GIRLS by Emma Cline, about the travails of a young woman who joins the family. Ultimately I’m unsure precisely how much those novels, despite their florid prose, differ from the likes of THE HIPPY CULT MURDERS or SWEET EVIL (or for that  matter the many nonfiction memoirs by former Manson family members), as based on what I’ve read of THE GIRLS it doesn’t appear to have much more insight into the Manson family than its down-market forebears.

matter the many nonfiction memoirs by former Manson family members), as based on what I’ve read of THE GIRLS it doesn’t appear to have much more insight into the Manson family than its down-market forebears.

There were some bright spots in the post-2000 flood of Manson lit, such as the lyrical and disquieting SWAY by Zachary Lazar. It dramatized a troika of deadly events—the drowning of Rolling Stones founder Brian Jones, the Stones’ notorious Altmont Speedway concert and the Tate-LaBianca murders—through the perspectives of several famous figures of the era, with a couple brief but memorable appearances by Manson. JESUS COYOTE by Harold Jaffe is likewise filtered through the POVs of various real life personages, including Roman Polanski and Susan Atkins (both appearing under assumed names), whose voices provide a notably kaleidoscopic “docufiction” rendering of the Tate-LaBianca killings and their aftermath.

And the madness has yet to subside, with new Manson-inspired films continually appearing, four of them in 2019 alone: the Hilary Duff headlined HAUNTING OF SHARON TATE (which Debra Tate has denounced as “Tacky, tacky, tacky”), a(nother) Leslie Van Houten biopic entitled CHARLIE SAYS (which proclaimed itself the “first” film to dramatize the female family members’ indoctrination), the nonviolent Sharon Tate biopic TATE, and of course Quentin Tarantino’s ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD. Tarantino’s film, I understand, has just crossed the $100 million mark at the US box office, proving that Manson mania is alive and well, just as it has been for the past fifty years and will doubtlessly remain