France’s Emmanuel Carrere is one of the most interesting writers on the scene, an author with whom genre buffs simply MUST become acquainted. He’s been called the “French Stephen King”, which doesn’t entirely do his work justice—certainly Carrere’s books lean toward the horrific and grotesque, but there’s far more to them.

France’s Emmanuel Carrere is one of the most interesting writers on the scene, an author with whom genre buffs simply MUST become acquainted. He’s been called the “French Stephen King”, which doesn’t entirely do his work justice—certainly Carrere’s books lean toward the horrific and grotesque, but there’s far more to them.

Carrere’s specialty is dislocation, in both the lives of his characters and the minds of his readers. Whether the subject is a man trying to come to grips with the fact that nobody seems to notice he’s shaved off his mustache or a “doctor” lying about passing a medical exam and then finding his life engulfed in an elaborate tissue of deceptions, in Carrere’s world the very fabric of reality is apt to shift irrevocably and without notice. His output includes three novels, a nonfiction study of a murderer and a highly eccentric biography of the legendary Philip K. Dick. The subject of the latter book seems appropriate, as Carrere’s writing is as weird and distinctive in its own way as Dick’s ever was.

Unfortunately for English speaking readers, translated editions of Carrere’s work have been slow to make their way to these shores. Thus far, just five Carrere titles have been published in English (with four or five more, including a study of the German filmmaker Werner Herzog, remaining untranslated), but all are well worth tracking down.

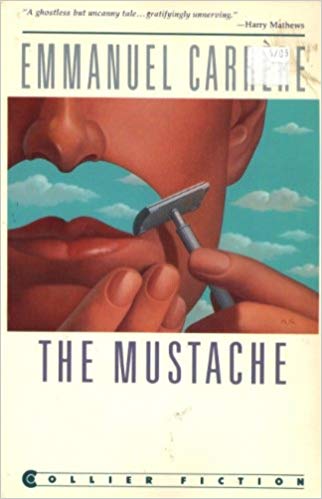

THE MUSTACHE [LA MOUSTACHE] (Collier Books; 1988) appeared first, and, despite the many critical accolades it received from the likes of John Updike  and others, is in my view the weakest of the bunch. That’s not to say it’s in any way a failure, though, being the intriguing, troubling little exercise in Kafka-esque apprehension that it is.

and others, is in my view the weakest of the bunch. That’s not to say it’s in any way a failure, though, being the intriguing, troubling little exercise in Kafka-esque apprehension that it is.

The author claims his primary inspiration for this book was not Kafka but the late Richard Matheson, and Matheson’s distinct brand of otherworldly paranoia is evident throughout this bizarre account of a man who on the advice of his wife decides to shave off his mustache. The problem is that once he’s done so his wife doesn’t seem to notice, much less remember that he ever had a mustache to begin with, and nor do his friends. Are they all playing a joke on him? Are they crazy? Is he? Such questions torment the poor guy to the point that he all-but loses his mind, dashing off to Hong Kong(!), where he becomes a drifter…and where a gruesome fate awaits.

No logical solution is offered for any of this, with a conclusion every bit as puzzling as the beginning. The novel does work, however, as a superbly unnerving look at the precarious hold we all have on our identities, and just how slippery it can become in this modern world where total insanity, it seems, is always right around the corner.

THE MUSTACHE, FYI, was made into a 2005 film written and directed by Carrere that’s now available on DVD. It’s a good adaptation, nicely capturing the book’s surreal paranoia, and even manages to improve upon the original ending—yet like the book, I ultimately found the film less than satisfying.

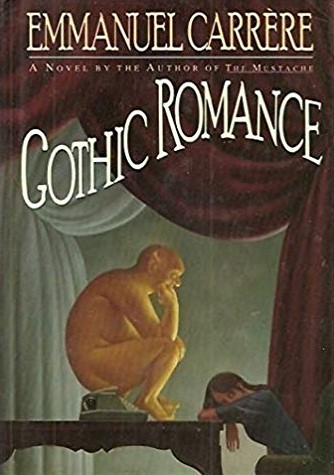

GOTHIC ROMANCE [BRAVOURE] (Scribner; 1990), published initially back in 1984 (the author’s second or third novel) and then revised for its English appearance six years later, is an even stranger work that takes a well-known historical event and twists it into a deliriously weird, sci fi-tinged concoction. It’s a literary treatment of the legendary evening in 1816 at Lake Geneva when Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and his wife Mary told ghost stories, during which the latter’s immortal FRANKENSTEIN was conceived. But Carrere’s take on the event, you can be sure, is unlike any other.

GOTHIC ROMANCE [BRAVOURE] (Scribner; 1990), published initially back in 1984 (the author’s second or third novel) and then revised for its English appearance six years later, is an even stranger work that takes a well-known historical event and twists it into a deliriously weird, sci fi-tinged concoction. It’s a literary treatment of the legendary evening in 1816 at Lake Geneva when Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and his wife Mary told ghost stories, during which the latter’s immortal FRANKENSTEIN was conceived. But Carrere’s take on the event, you can be sure, is unlike any other.

It starts off after the fact, with John Polidori, Lord Byron’s meek doctor who was inspired to write THE VAMPIRE that fateful evening, in a severely depressed state because he believes Mary Shelley stole the concept of FRANKENSTEIN from him. The point of view then shifts to Captain Walton, Polidori’s alter ego, who writes a confession in which he reveals that he’s discovered a way to bring dead folks back to life…and that Mary Shelley is one of his undead subjects. From there the narrative leaps into the modern world, where a young woman works for the mysterious Captain Walton writing hack romance novels. The woman stumbles onto what appears to be a conspiracy to overrun the world with zombies; her employer, it seems, is part of a movement begun by John Polidori that’s dedicated to resisting the conspiracy. But then the narrative shifts yet again for a final sequence told from the point of view of Mary Shelley, who recalls the fateful night her masterpiece was created and gives vent to quite a few scattered neuroses in the process.

What exactly is the point of this time-tripping phantasmagoria? Is it all meant to be a dream? A hallucination? Or is the science ficitonish mid-section the “real” part? The book never quite reveals its hand, but for the most part makes for fascinating historical speculation tinged with old-fashioned pulp thrills. (Interested parties might also want to check out THE MERCIFUL WOMEN by Spanish author Federico Andahazi, a similarly whacked-out treatment of the same events that posits Shelley and Polidori’s writings were actually cranked out by a vampire hag who required male semen to stay alive!)

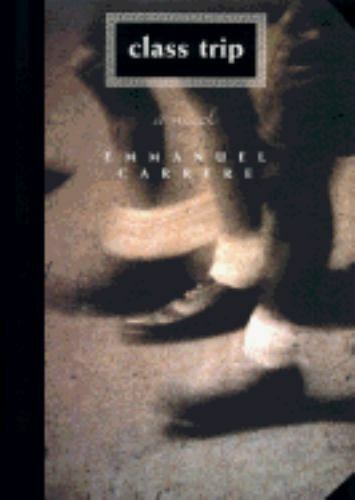

CLASS TRIP [LA CLASSE DE NEIGE] (Henry Holt; 1997) is another unique exercise in unrest. A short (162-page) novel, it’s not perfect, but is in my view  Carrere’s strongest work of fiction, a subtly unnerving, impressively concentrated peek into the unquiet mind of Nicolas, a profoundly shy, almost too-sensitive-for-this-world tyke whose world unravels during a ski outing with his teachers and schoolmates.

Carrere’s strongest work of fiction, a subtly unnerving, impressively concentrated peek into the unquiet mind of Nicolas, a profoundly shy, almost too-sensitive-for-this-world tyke whose world unravels during a ski outing with his teachers and schoolmates.

Things start off on the wrong foot when Nicolas’ dad refuses to allow him to ride the bus with the other kids, insisting on driving Nicolas to the ski lodge himself. There he dumps Nicolas and promptly drives off, forgetting to unpack his son’s suitcase. Everybody waits for Nicolas’ father to show up with his things but nothing is heard from him, and Nicolas, already retreating into a fantasy world weaned on books, TV and the wild yarns spun by his dad, imagines that his father has been killed. The truth, of course, is far worse, and made manifest when a kid from a nearby town is found murdered.

The book has a powerfully macabre air, and its depiction of a disturbed child’s private universe is entirely convincing. Of course, I didn’t find that child especially sympathetic, being as he is maladjusted and self-absorbed to a near-insane degree, but it’s a testament to the author’s skills that Nicolas’ foibles register with such unnerving vividness.

The nonfiction THE ADVERSARY [L’ADVERSAIRE] (Metropolitan Books; 2000) followed, and may well be Carrere’s masterpiece. It’s certainly one of the most shattering books I’ve ever read, an account of criminality with profoundly disturbing real-life implications, especially for us non-criminals.

The nonfiction THE ADVERSARY [L’ADVERSAIRE] (Metropolitan Books; 2000) followed, and may well be Carrere’s masterpiece. It’s certainly one of the most shattering books I’ve ever read, an account of criminality with profoundly disturbing real-life implications, especially for us non-criminals.

Jean-Claude Romand is the subject, a Frenchman who for nearly two decades convinced his friends and family that he was a successful doctor when in fact he was unemployed and siphoning money from them in the guise of shadowy “investments”. When his façade was threatened Romand methodically killed his wife, children and parents and then unsuccessfully tried to take his own life.

Carrere began corresponding with Romand shortly thereafter, and pieced together the details of his life through personal correspondence and Romand’s court testimony. What emerges is not the amoral psychopath you might expect but a kind-hearted (if extremely weak) man who back in the seventies lied about taking a college entrance exam and then found the resulting deceptions and half-truths escalating until they literally consumed his life. Carrere, in deceptively quiet fashion, puts us in firmly in Romand’s shoes as his invented life spins out of control; eventually he’s driven mad by the pressures of maintaining his façade and becomes a jittery wreck—and a murderer.

What makes the book so effective is the way Carrere forces us into an uncomfortable empathy with his tragic subject. Who among us, after all, hasn’t told a “white lie” at least once in his/her life and then tried like Hell to cover it up? The title, incidentally, refers to the Devil, who Carrere suggests was whispering in Romand’s ear throughout his life…just as He does with the rest of us.

I AM ALIVE AND YOU ARE DEAD: A JOURNEY INTO THE MIND OF PHILIP K. DICK [JE SUIS VIVANT ET VOUS ETES MORTS] (Metropolitan Books;  2004) is one of the latest Emmanuel Carrere books to appear on these shores. It proves to me that Carrere, while known primarily as a writer of fiction, is actually at his best with biographical portraits of real folks, as demonstrated by the above book and this unforgettable portrait of the one and only Philip K. Dick. Initially published in 1993, it’s something of a dream for weird book buffs like me.

2004) is one of the latest Emmanuel Carrere books to appear on these shores. It proves to me that Carrere, while known primarily as a writer of fiction, is actually at his best with biographical portraits of real folks, as demonstrated by the above book and this unforgettable portrait of the one and only Philip K. Dick. Initially published in 1993, it’s something of a dream for weird book buffs like me.

It has, however, proven quite controversial among PKD fanatics, many of whom resent Carrere’s take on one of science fiction’s all-around masters, a man who stood out from the pack by virtue of the fact that he actually believed in many of the bizarre scenarios he wrote about. As a die-in-the-wool “Dickhead” I’ll concede that many of Carrere’s conclusions about his subject are questionable, including his over-insistence on using Dick’s fiction to detail the facts of his life, when in fact the two were more often than not poles apart (see Laurence Sutin’s DIVINE INVASIONS, still the definitive biography of PKD). That said I find Carrere’s book an indispensable resource, a wildly unorthodox yet compulsively readable experiment in subjective biography.

Dispensing with the usual biographical implements of quotes and an unbiased point of view, Carrere delves deeply into PKD’s disturbed psyche, relating his many visions and delusions with hallucinatory vividness. Dick, as you probably know, cranked out thirty or so sci fi novels that he increasingly came to believe represented the true reality, in whose shadow our day-to-day existence is but a façade. Over the course of his life Dick suffered from a series of failed relationships and a far too-copious drug intake, and during the seventies experienced a plethora of hallucinations that only increased his inborn paranoia and misanthropy, culminating in a near-indescribable mystical encounter related in his novel VALIS.

Carrere does what he can to render Dick’s visionary experiences coherent, and mostly succeeds. The author also details and critiques a number of Dick’s novels, including CLANS OF THE ALPINE MOON, THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRICH and UBIK, all of which, Carrere argues, are indispensable to an understanding of PKD’s life. Again, I don’t entirely agree with that claim, but do admire the skill and audacity with which Carrere pulled this wildly off-kilter book together.

And so ends my too-brief overview of the books of Emmanuel Carrere. As stated above, these five books represent only half of Carrere’s total output. Thankfully all but one (GOTHIC ROMANCE) are still in print—let’s hope the author’s other works follow!