Nuclear war, as we all well know, has been the subject of many a movie. In the 1950s we had, among others, FIVE, ATTACK OF THE CRAB MONSTERS and ON THE BEACH. The sixties gave us PANIC IN YEAR ZERO, FAIL-SAFE and DR. STRANGELOVE. From the seventies there was A BOY AND HIS DOG, DAMNATION ALLEY and MAD MAX, while more recent years have brought the likes of THE ROAD, THE BOOK OF ELI and THE DIVIDE.

Those films are all speculative dramas that take place during the present or near future, and deal with the possibility of a nuclear holocaust in fantasy oriented terms (and often feature zombies, mutant crabs, telepathic dogs and giant scorpions). Most ignored the realities of climate change and radiation poisoning that would assuredly befall the Earth in the event of a nuclear Armageddon. In some of those movies a post-nuke world actually looked like fun, fostering a spirit of strength and individuality in those fated to live through it.

The 1980s, however, saw a different kind of nuke movie. These films often shared the speculative arc of the others but were patterned more on Peter Watkins’ infamous 1965 mock-documentary THE WAR GAME, a pitiless and unflinching portrayal of the true horrors of nuclear war.

The seven films outlined below span the years 1981-86. They’re quite varied in origin (emerging from the USA, England, France, Russia and even Australia), distribution venues (two were made for television) and format (one is animated), yet linked by their staunch reality-based outlook. In all cases this makes for profoundly depressing, shocking and traumatizing viewing. In the words of THE DAY AFTER director Nicholas Meyer, “The great and terrible paradox about the nuclear issue is that while it remains the single most important dilemma to confront the human race, it is at the same time so dreadful that no one in his right mind can bear to contemplate it.”

These films are obviously far removed from more fanciful eighties-era nuke flicks like AFTER THE FALL OF NEW YORK, MAD MAX BEYOND THUNDERDOME, Andrei Tarkovsky’s quasi-mystical THE SACRIFICE and the rollicking thrillers WAR GAMES and MIRACLE MILE. Another aspect that sets the following films apart is that nearly all of them remain alarmingly relevant today. The Cold War may be over, but the threat of nuclear devastation hasn’t gone away.

First up is MALEVIL from 1981, a French made account of life in the wake of a nuclear catastrophe that’s as bleak as can possibly be imagined. (See MALEVIL Review for video clip.) The early scenes are strong and chilling, with the mayor of a rural village finding himself trapped in the wine cellar of his home together with several farmhands as the world is nuked. Director Christian de Chalonge effectively conveys the effects of the catastrophe through an accumulation of minute details (wine corks popping, etc), while the ensuing exterior shots are equally effective in their depiction of a charred landscape afflicted by rains of ash.

How unfortunate, then, that the film degenerates completely in its second half, wherein the sky clears up and a band of fascistic assholes show up to challenge the protagonists. The ensuing conflict should be far more exciting than it is; Chalonge’s heart clearly wasn’t in the action and violence, which is fully evident in the ultra-staid climactic shoot-out and subsequent helicopter rescue.

(See MALEVIL Review for video clip.)

Next is THE DAY AFTER, the most famous of these particular films. It was an ABC TV movie broadcast in the U.S. on November 20, 1983. The showing was a major media event complete with toll-free hotlines set up to calm viewer alarm and a deliberate absence of commercials during the program’s latter half.

The setting is a small Kansas town ripped apart by nuclear war. Director Nicolas Meyer (coming off STAR TREK 2) immerses us in the lives of several of the town’s residents, including Jason Robards as a curmudgeonly doctor, Jobeth Williams as his fetching assistant, Steve Guttenberg as a kind-hearted drifter and John Lithgow as a law enforcement officer.

The scenes leading up to the nuclear blasts, pulled off with a near avant-garde juxtaposition of prosaic long shots and ultra kinetic cross cutting, are unlike anything else on American television (then or now), and very likely the finest work Nicholas Meyer has ever done as a director. The remainder of the film is laudable in its depiction of the likely outcome of a nuclear attack (excepting the ultra-primitive special effects), with its characters succumbing to radiation sickness amid soot-covered landscapes.

Unfortunately, the whole thing is obnoxiously sentimental in its approach, and more than a little sanitized. That’s due (so Meyer has claimed) to meddling by ABC’s executives, and the dictates of the TV Standards and Practices board. Yet it’s also a fact that President Ronald Reagan was moved to curb his nuclear ambitions after viewing THE DAY AFTER, so it’s not entirely without worth—even if it pales in light of the like-minded films that followed.

One of those films was TESTAMENT, released in December of 1983. The setting this time is a California suburb, where an unassuming housefrow (Jane Alexander) resides with her husband (William Devane) and three children.

It’s easy to scoff at the early scenes, with their cuddly depiction of small town Americana. Director Lynne Littman does such a thorough job setting up the ordinariness of this suburban milieu that it’s downright stunning when, about 20 minutes in, a nuclear explosion occurs nearby. The town is far enough from the blast that it comes through intact…though far from unscathed.

There’s no electricity, so everyone’s food goes bad. Worse, Alexander’s husband never returns home from work, and her children begin succumbing to radiation sickness. Alexander and her fellow townspeople desperately try to carry on with their normal routine, even going ahead with a school play (despite the fact that many of the performers are dead or on their way). Things eventually get so bad that Alexander and her surviving child decide to asphyxiate themselves in her garage. They don’t carry through with the act, but the inescapable conclusion is that they’re not long for this world whatever they do.

Jane Alexander is unforgettable in the lead role, and her gradual transformation from a strong-willed matriarch to a complete basket case, which mirrors TESTAMENT’s overall arc, is positively gut-wrenching.

Back in the eighties it was often thought that Australia would be an ideal place to be in the event of a nuclear war. The Australian made ONE NIGHT STAND, from 1984, suggests otherwise.

It’s centered on four wayward young folk, one of them an AWOL American sailor, looking to ride out an impending nuclear war in the Sydney Opera House. But following a lot of aimless chatter during which cherished memories are aired (complete with some elaborate flashbacks) the twerps are forced out, and wind up in a subway tunnel along with hundreds of anonymous refugees while the world is decimated above them.

The sense of approaching menace that suffuses these scenes, and the movie overall, is what really distinguishes ONE NIGHT STAND. Here the question isn’t if, or even when, the missiles will hit, but rather how horrendous the damage will be when they do.

Too bad the pic is otherwise misconceived and dull. Among other sins, writer-director John Duigan tries for a quirky comedic tone in the early scenes that doesn’t work at all—DR. STRANGELOVE aside, comedy and nuclear war simply don’t mix.

The same year’s THREADS, the BBC’s answer to THE DAY AFTER, is something else entirely. (See THREADS Review for video clip.) Scripted by novelist Barry Hines and directed by future Hollywood hack Mick Jackson, it may well be the most powerful—and powerfully depressing—nuke movie ever made, and also the one that comes closest to capturing the unspeakable reality of a nuclear conflict.

The setting is the British suburb Sheffield, which is affected in profoundly horrific fashion after the United Kingdom is nuked (in an admittedly tacky sequence toward which you’ll have to be forgiving). Wounded people overwhelm the hospitals, food becomes scarce and mass riots erupt. Authorities are forced to adopt fascistic measures to control the increasingly barbaric populace, and corpses are left to molder in the streets (as burying them would require too much manpower).

In contrast to the sentimentality of THE DAY AFTER, whose protagonists were largely concerned with setting things right with their loved ones, THREADS is resolutely hard-nosed and unforgiving. Its characters are consumed above all else with day-to-day survival, which poses quite a challenge in this world gone mad.

The highly expansive narrative spans thirteen years, during which Sheffield and its citizenry literally regress back to the stone age. Mick Jackson’s limited budget doesn’t entirely support such a grandiose canvas, but Jackson makes the most of his limitations in consistently inventive and resourceful fashion. The result is a masterful piece of filmmaking, though also a profoundly harsh one.

(See THREADS Review for video clip.)

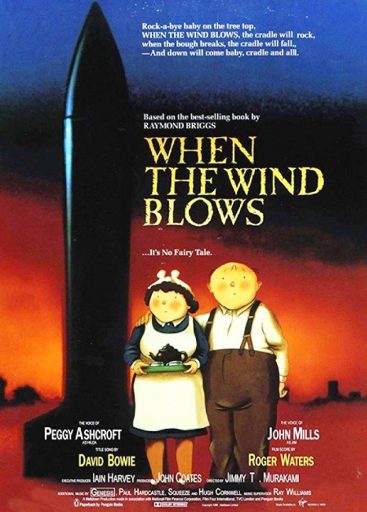

WHEN THE WIND BLOWS (1986) is another British production, and another change of pace. Directed by the late Jimmy T. Murakami (of the Roger Corman production BATTLE BEYOND THE STARS), it’s an animated drama highlighted by impressively detailed character design.

Based on a graphic novel by Raymond Briggs, it’s about Jim and Hilda Blogg, an elderly couple living out their retirement in a secluded mesa. Finding themselves unharmed after nuclear missiles decimate London (about halfway through the movie), the Bloggs, like the protagonists of the abovementioned TESTAMENT, try their damndest to get back to normal, but inexorably fall prey to starvation and radiation sickness.

Watching these loveable coots slowly deteriorate makes for profoundly disturbing and heartrending viewing. The Bloggs, superbly voiced by John Mills and Peggy Ashcroft, may be cartoons, but by the end of this film’s 80 minutes you’ll feel as if you’ve spent time with two flesh-and-blood individuals, which makes their demise all the more devastating.

The only distractions are the gratuitous psychedelic interludes (inserted, apparently, to remind us the film’s producer John Coates also worked on THE YELLOW SUBMARINE). Great music, though, by Roger Waters, Genesis and David Bowie.

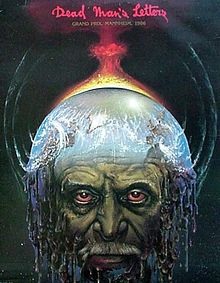

Finally we have LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN, also emerging from 1986. (See LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN Review for video clip.) It’s yet another dramatization of the aftermath of a nuclear war, this one emerging from the other side of the Cold War fence: the late Soviet Union. Yet it’s every bit as harsh and unsparing as any of its American and British forebears.

In this shattering film civilization is (again) devastated, with the shell-shocked survivors subsiding in rubble-strewn hovels. The outside world is even more horrific, marked by massive piles of rubble and dead bodies scattered everywhere. The central character is a Nobel Prize-winning professor who writes letters to his dead son while desperately trying to frame his situation in logical, easy-to-grasp terms. This he can’t do, of course, as he and his doomed companions are trapped in a perpetual nightmare of madness and despair.

Director Konstantin Lopushansky has created one of the most grimly convincing post-nuke environments I’ve ever seen in a film. It’s visualized in differing tints of black and white, a choice that gives the proceedings just the right touch of otherworldliness. The film may be grimly realistic, but it also has a highly poetic and ethereal angle: Lopushansky was a protégée of the late Andrei Tarkovsky, and the latter’s influence is evident in the long shots, measured pacing and oft-dreamlike atmosphere.

(See LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN Review for video clip.)

Obviously these films aren’t conventional entertainments—far from it—but all are important, being among the very few “message” movies whose message is truly vital. They should be required viewing for all the world’s leaders (THREADS and LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN in particular), because if anything can be expected to make them think twice about pushing the button it’s these seven mind-rending downers.

While I’m at it, I’ll mention two further films that turned up on American television around the same time THE DAY AFTER and THREADS were terrorizing unsuspecting couch potatoes. The programs described below differ from the above in their concern with the hows and whys of a nuclear exchange rather than the aftermath, but they share a propulsive sense of fact-based outrage.

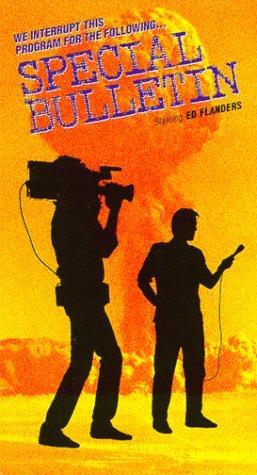

SPECIAL BULLETIN (1983), directed by the future Hollywood hotshot (and THIRTYSOMETHING creator) Ed Zwick, deserves points for audacity. Presented entirely as a series of “Special Bulletins” by a TV news crew, it tries very hard to be a WAR OF THE WORLDS-styled scare inducer, but just never feels real. (Nonetheless, NBC received hundreds of alarmed calls when it was originally broadcast from viewers who evidently thought otherwise.)

The “plot” concerns a gang of unhinged peaceniks who hijack a fishing boat and threaten to set off a nuclear bomb. The newscasters grow increasingly alarmed by the situation, and break into frequent on-air arguments about their culpability in the unfolding madness. In keeping with the grimness of the subject matter, the pic concludes on the most downbeat note imaginable.

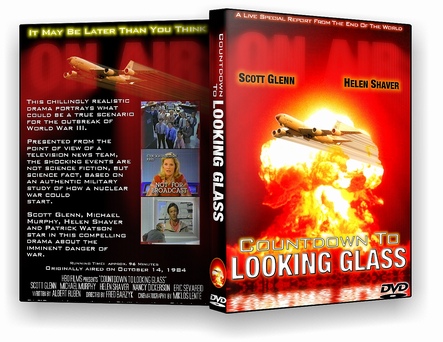

While quite compelling in its way, I’d say SPECIAL BULLETIN works best as a time capsule, effectively capturing the paranoid mood that suffused America at the height of the cold war.The Canadian-made COUNTDOWN TO LOOKING GLASS, broadcast on HBO in 1984, is quite similar in many respects to SPECIAL BULLETIN. It’s also done up as a series of fakes news alerts, and also quite dated in most respects. It still packs a wallop, however, due largely to the fact that the events it depicts—a worldwide financial meltdown leading to increased tensions in the Middle East that ultimately trigger a nuclear conflict—contain many unsettling parallels to our current situation.

The fictitious program at the film’s center is a CNN-styled cable news show whose key reporters are played by Helen Shaver and Scott Glenn. Also on hand are several actual political figures (including Senator Newt Gingrich) to make the proceedings seem more realistic.

COUNTDOWN TO LOOKING GLASS is at its best in the fake broadcasts, wherein stock news footage is cleverly re-contextualized to serve the filmmakers’ ends. Especially powerful is a climactic nuclear explosion, with a harried Glenn seen buffeted by blinding light from the blasts and his video feed cutting in and out. It’s a true nightmare-inducer, made all more forceful by the fact that it, as with most every other movie outlined herein, is one bad dream could well become our reality.