The decline of print media is a subject that in the post-Coronavirus era has taken on a new relevance. Libraries have been disproportionately affected, as it seems ebooks are destined to be the major library check-out items. This would appear to be accelerating a process that began some time ago, with the ascension of a format that had existed for some time but only really got going (so history tells us) in 2003, when libraries began offering downloadable ebooks. From there, as they say, it’s all been downhill as far as print media is concerned.

The decline of print media is a subject that in the post-Coronavirus era has taken on a new relevance. Libraries have been disproportionately affected, as it seems ebooks are destined to be the major library check-out items. This would appear to be accelerating a process that began some time ago, with the ascension of a format that had existed for some time but only really got going (so history tells us) in 2003, when libraries began offering downloadable ebooks. From there, as they say, it’s all been downhill as far as print media is concerned.

See OUT OF PRINT (2013), a 50 minute made-for-Italian television documentary about how ebooks have transformed the literary landscape. The information doled out here, by the likes of PRESUMED INNOCENT author Scott Turow, Jeff Bezos, a New York Times columnist and several other learned folk, is nothing I didn’t already know, but the pic’s conclusions are depressingly accurate. In essence, it claims that e-books are here to stay, for better or (more likely) worse. Also covered are the detrimental effects of digital media on developing minds, with children apparently no longer able to absorb large blocks of information, or even utilize the library system.

By now, of course, a large percentage of the world’s printed matter is digitally available, and, like it or not, seems destined to be preserved in that format—but there are some outliers. An example would be THE ASTROLOGER, a long out of  print 1972 novel by JOHN CAMERON that as of 2020 has yet to be digitized (about which I haven’t heard too many complaints).

print 1972 novel by JOHN CAMERON that as of 2020 has yet to be digitized (about which I haven’t heard too many complaints).

The novel was adapted for film in 1975, in the form of James Glickenhaus’ SUICIDE CULT (Glickenhaus, for the record, was dating John Cameron’s daughter, and is credited with the author photo in THE ASTROLOGER’S hardcover edition). That film is legendarily bad, but the book, it turns out, is a pretty dull affair—albeit with some intriguing concepts. It’s about a brilliant astrologer, Alexei Abernel, who founds a CIA funded organization that gathers data on everyone in the world to ascertain their “Zodiacal Potential.” This is to say that Abernel and co. can accurately predict one’s destiny by the position of the stars at his/her birth, combined with the environmental factors surrounding said birth.

This is a far more complicated concept than it might seem, as it takes the author nearly half the book to fully explain it. Much of the rest is taken up with a scheme to take down a ruthless Indian tyrant whose Zodiacal Potential is deeply unsettling, and an attempt by Abernel to figure out if his wife is the reincarnation of the Virgin Mary. Interesting, but none of it is particularly exciting, as the book consists mostly of talk. The ending is also a letdown, intimating that Abernel’s wife may have already birthed the messiah and given Him up for adoption—but alas, nobody can seem to find the kid.

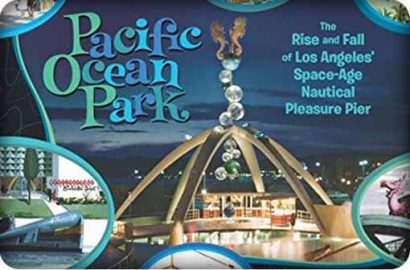

Speaking of things unfound: the late Pacific Ocean Park was a nautical themed, Santa Monica based amusement park  that’s now long gone. Speaking as a longtime Southern California resident, I found the 2014 coffee table book PACIFIC OCEAN PARK by CHRISTOPHER MERRITT and DOMENIC PRIORE, which presents an admirably thorough accounting of the park with extensive photographic illustrations, a most welcome and enjoyable history lesson.

that’s now long gone. Speaking as a longtime Southern California resident, I found the 2014 coffee table book PACIFIC OCEAN PARK by CHRISTOPHER MERRITT and DOMENIC PRIORE, which presents an admirably thorough accounting of the park with extensive photographic illustrations, a most welcome and enjoyable history lesson.

Utilizing historical records and the firsthand recollections of people who experienced the place in its prime, PACIFIC OCEAN PARK relates how POP came about as a beachfront rival to Disneyland, a gaudily designed pleasure pier containing rides and themed restaurants. POP’s 1958 opening was apparently quite a big deal but its fortunes went steadily downhill, affected by corrosive ocean air, disapproving Santa Monica city officials and widespread public disinterest. This was despite the fact that POP was a favored setting in sixties-era television (it was prominently featured in THE TWILIGHT ZONE, GET SMART and THE FUGITIVE), and also played host to a popular teenybopper variety show.

Pacific Ocean Park was shuttered in 1967, leaving behind a moldering ruin that became a haven for transients and daredevil surfers eager to sample the waves created by its presence. Eventually the structure was torn down entirely, and nowadays nary a trace of the POP’s existence remains. As its final owner Jack Roberts is quoted as stating, “with dreams, you do your best to keep them going, but finally the executioner comes stomping in with an ax…”

Not that an ex is needed for that particular job, or even an executioner. All consuming love, it seems, can do that just as  well. In 1973’s THE LESBIAN BODY by France’s late MONIQUE WITTIG (translated by David Le Vay), affection takes the place of sentencing and cannibalism that of execution.

well. In 1973’s THE LESBIAN BODY by France’s late MONIQUE WITTIG (translated by David Le Vay), affection takes the place of sentencing and cannibalism that of execution.

The novel is a quasi-sequel to its author’s 1969 tome LES GUERILLERES, a popular feminist text about lesbians overthrowing the male order and retiring to a vast forest. In THE LESBIAN BODY the women have settled into this apparent paradise, where they perform elaborate sex rituals that more often than not involve the participants literally devouring each other. The many cannibalistic descriptions were likely intended to be metaphoric, but in this English translation are a bit too literal (“I succeed thus in making your eyeball topple out…I take it between my lips, I squeeze it, I make it roll entire within my mouth…I suckle at it, I swallow it”).

Another translation issue I have is with Le Vey’s rendering of one Wittig’s most prominent linguistic quirks: the use of slashes between the letters of Je, which means I in French. The author’s aim was to break down gender designations (which in the French language are quite rigidly adhered to, extending even to inanimate objects), but it doesn’t register in English, in which we’re given “m/y” and “m/e,” which don’t have the intended effect.

Then there’s the jumbled non-narrative, consisting entirely of disjointed sexual encounters, each related in the form of an ecstatic address to an unidentified lesbian lover. I found it annoying, although taken purely as a curiosity this book has some value.

Curiosity? That accurately describes PINOCCHIO IN OUTER SPACE (1964), a French-made, English dubbed kiddie kartoon that’s pretty worthless overall, but far weirder than I expected. It’s an ersatz sequel to PINOCCHIO in which that character, having been turned from a wooden puppet into a real boy, gets changed back after he goofs off and causes trouble. A Space Turtle then lands in his backyard and whisks him away to take on Astro the Space Whale, but this entails a detour to Mars, and a stairway that leads underground, home to giant crabs, whales and even a few dinosaurs. Later Pinocchio and the Space Turtle manage to hypnotize Astro by flying their spaceship in a circle, but that only sends him hurtling toward the earth.

Curiosity? That accurately describes PINOCCHIO IN OUTER SPACE (1964), a French-made, English dubbed kiddie kartoon that’s pretty worthless overall, but far weirder than I expected. It’s an ersatz sequel to PINOCCHIO in which that character, having been turned from a wooden puppet into a real boy, gets changed back after he goofs off and causes trouble. A Space Turtle then lands in his backyard and whisks him away to take on Astro the Space Whale, but this entails a detour to Mars, and a stairway that leads underground, home to giant crabs, whales and even a few dinosaurs. Later Pinocchio and the Space Turtle manage to hypnotize Astro by flying their spaceship in a circle, but that only sends him hurtling toward the earth.

There’s enough invention here to almost make me believe that the film’s creators might have actually given a damn about what they were doing, but the clunky pacing, listless animation and lousy music numbers disabused me of that ridiculous notion. The latter point, incidentally, is one that has long irritated me about kid movies: the need to insert gratuitous songs into ‘em whether the material calls for it or not. This tendency, of course, isn’t limited to family fare. The experimental provocation NICE TO MEET YOU, PLEASE DON’T RAPE ME! is far from kid-friendly, yet contains music numbers that are just as dopey and out-of-place as those of PINOCCHIO IN OUTER SPACE.

NICE TO MEET YOU… is a statement of sorts on the rape culture of South Africa by the South African bred, Netherlands based experimental filmmaker Aryan Kaganof. It follows a trio of scumbag males who break into houses and periodic song and dance numbers, attend a class of sorts taught by a radical feminist and eventually turn on each other. The subject in all cases is rape, the particulars of which are sung about, discussed at length and eventually enacted by the protagonists (on each other).

There’s no story to speak of, and without a thorough knowledge of the culture of South Africa it will all seem pretty incomprehensible. But the film is attention getting, with a fair amount of graphic nudity and sex. Another plus is that in 2009 Kaganof reedited this 1995 film (made back when he was known as Ian Kerkhof) from its initial 70 minute runtime to half that length, so at least nobody can say it’s too long.

It’s a shame the same treatment can’t be applied to American paperback originals of the 1980s, which by and large tend to be vastly overlong, overwritten and overwrought. 1981’s THE BURIED  by DANIEL HELFGOTT is a textbook example of those things. In fairness, it’s decent enough for what it is, but what it is really isn’t much.

by DANIEL HELFGOTT is a textbook example of those things. In fairness, it’s decent enough for what it is, but what it is really isn’t much.

It’s a thriller in which a burly American man is drawn into a hunt for Incan treasure in the Amazon rain forest, making for a suitably old-fashioned adventure—albeit one with a fair amount of very up-to-date sex and violence. This adventure also entails the protagonist getting back together with his ex-wife, who joins the jungle hunt, only to be separated from her ex once again when Incan descended natives attack. The guy ends up becoming part of the tribe and getting amorously involved with one of its more hot-to-trot female members, but has to contend with rival natives and fellow Caucasian treasure hunters. It concludes with lots of Hollywood-friendly fire power and a big explosion (suggesting that the story may have been conceived with a movie sale in mind).

THE BURIED is reasonably well written and knowledgeable about the subject matter it presents, but it could—and should—have been much livelier, suffering as it does from a shockingly slow pace, an uneventful narrative that could have done with some twists and an overly expansive page length. Pulp fiction tends to work best in short bursts, whereas this very pulpy novel insists on taking its sweet time.

The inverse of pulp is of course prestige. Every medium has its prestigious, award caliber realm, even Germany in the  silent film era. Back then nobody was more esteemed than director Fritz Lang and his then wife and collaborator Thea von Harbou, who gave us classics like DR. MABUSE THE GAMBLER (1922), DIE NIBELUNGEN (1924), METROPOLIS (1927) and M (1931). Von Harbou was also the scripter of THE CHRONICLES OF THE GREY HOUSE (ZUR CHRONIK VON GRIESHUUS), a prestige item hailing from 1925.

silent film era. Back then nobody was more esteemed than director Fritz Lang and his then wife and collaborator Thea von Harbou, who gave us classics like DR. MABUSE THE GAMBLER (1922), DIE NIBELUNGEN (1924), METROPOLIS (1927) and M (1931). Von Harbou was also the scripter of THE CHRONICLES OF THE GREY HOUSE (ZUR CHRONIK VON GRIESHUUS), a prestige item hailing from 1925.

The film has been widely renowned for its visuals, and yes, from a pictorial standpoint it is indeed impressive. Depicted is a fully realized medieval mini-universe, specifically a rural kingdom in which the son of a landowner falls in love with the daughter of a serf, leading to all sorts of trouble.

Narratively the film is a jumble, being quite diffuse and difficult to follow. Perhaps the problem is that (as an imdb user has opined) the material isn’t suited to the silent medium, or (more likely) that director Arthur von Gerlach was vastly out of his depth helming what should have been a Fritz Lang production.

Wrongfully chosen directors have ruined many a film over the decades. One of the pluses of reality television, at least from a producer’s standpoint, is that it’s not dependent on directorial prowess. This is evident in what is perhaps the most famous reality TV program of them all: SURVIVOR, which has had a run of twenty years and 40 seasons. To see how this phenomenon got started, check out 2000’s SURVIVOR: THE OFFICIAL COMPANION BOOK by the show’s executive producer MARK BURNETT and MARTIN DUGARD, which chronicles the very first season.

Back then SURVIVOR, difficult though it might seem to believe now, seemed fresh and interesting (and not a little  terrifying). This book details the frustrations and schemings of its sixteen civilian castaways, one of whom stood to win a million dollars, stranded on a deserted island in Borneo with a camera crew recording their every move. It’s clear that Burnett was just as curious about the castaways’ activities as the rest of us, and he goes into great detail about their backgrounds.

terrifying). This book details the frustrations and schemings of its sixteen civilian castaways, one of whom stood to win a million dollars, stranded on a deserted island in Borneo with a camera crew recording their every move. It’s clear that Burnett was just as curious about the castaways’ activities as the rest of us, and he goes into great detail about their backgrounds.

The book contains a great deal of information that didn’t make it into the program, such as the fact that contestant Greg Buis came onto the eventual winner “Gay Rich” Hatch in order to curry favor, and that the seemingly-unflappable host Jeff Probst was somewhat temperamental (storming off the set after being embarrassed at a tribal council, fuming “I never want that to happen again!”). Burnett also details behind-the-scenes drama that, with equipment-destroying rains and a near-fatal boat accident, was almost as arduous as what we saw onscreen. This is an interesting read if you’re a SURVIVOR fan, or even if you’re not (I myself gave up on the show after the second season).

And, to bring this rambling article full circle, as of 2020 neither this book nor its 2001 follow-up SURVIVOR II: THE FIELD GUIDE (likewise co-authored by Burnett) are available in ebook format—and what that might (or might not) say about modern-day technology I really don’t know.