Continuing with my “Essentials” horror surveys (see here, here, here and here for the others) we arrive at the Netherlands, which isn’t exactly a hotbed for horror fare. The 1969 German co-production OBSSESSIONS, co-scripted by a young Martin Scorsese and directed by Pim de la Parra, is among the best known Dutch horror films, which is the only positive designation that lackluster effort gets from me (although I do recommend Parra’s terrifically bizarre 1985 film PAUL CHEVROLET AND THE ULTIMATE HALLUCINATION/PAUL CHEVROLET EN DE ULTIEME HALLUCINATIE).

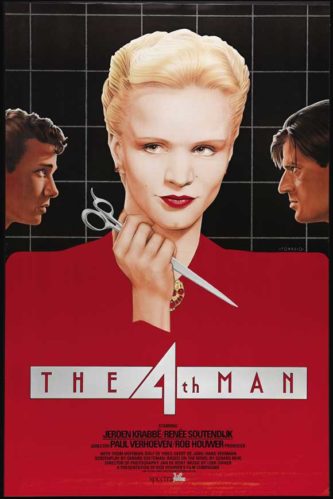

Nonetheless, there are a handful of quality horror films to be found in the Netherlands, starting with 1983’s THE 4th MAN (DE VIERDE MAN). Its maker was Paul Verhoeven, who prior to decamping for Hollywood in the late 1980s was the Netherlands’ top filmmaker. Anyone familiar with BASIC INSTINCT, Verhoeven’s biggest hit, will note a distinctive sensibility, as for that matter will viewers of his earlier films. THE 4th MAN’S stars Jeroen Krabbe and Renee Soutendijk were Verhoeven regulars, from SOLDIER OF ORANGE/SOLDAAT VAN ORANJE (1977) and SPETTERS (1980), respectively, as was screenwriter Gerard Soeteman, the writer of all Verhoeven’s previous films (and many of his subsequent ones).

Nonetheless, there are a handful of quality horror films to be found in the Netherlands, starting with 1983’s THE 4th MAN (DE VIERDE MAN). Its maker was Paul Verhoeven, who prior to decamping for Hollywood in the late 1980s was the Netherlands’ top filmmaker. Anyone familiar with BASIC INSTINCT, Verhoeven’s biggest hit, will note a distinctive sensibility, as for that matter will viewers of his earlier films. THE 4th MAN’S stars Jeroen Krabbe and Renee Soutendijk were Verhoeven regulars, from SOLDIER OF ORANGE/SOLDAAT VAN ORANJE (1977) and SPETTERS (1980), respectively, as was screenwriter Gerard Soeteman, the writer of all Verhoeven’s previous films (and many of his subsequent ones).

Adapted from a semi-autobiographical novel by Gerard Reve, the film features Krabbe as, appropriately enough, Gerard Reve, a gay alcoholic writer who finds himself beset by grotesque (and possibly prophetic) hallucinations, which kick into overdrive when he meets the sexy Christine (Soutendijk). Attracted by her androgynous looks, Gerard is drawn into a sexual relationship with her. As the relationship progresses Gerard discovers that Christine has had three previous husbands, all of whom died under mysterious circumstances. Did she in fact murder them? And if so, is Gerard to be the fourth victim? His continuing hallucinations, which seem to be bleeding more and more into reality, certainly point to that possibility.

Verhoeven’s kinetic, fast-moving style fits the subject matter well. His trademarked roving camerawork is even more jittery than usual, giving us a pitch-perfect visual representation of the main character’s increasingly fractured mental state. In contrast to the stark naturalism of Verhoeven’s previous films, THE 4TH MAN is, like his subsequent Hollywood pictures, heavily stylized and deliberately artificial. It’s also, in keeping with ALL Verhoeven’s work, utterly unsparing in its depiction of extreme sex and violence (full front male and female nudity are constant).

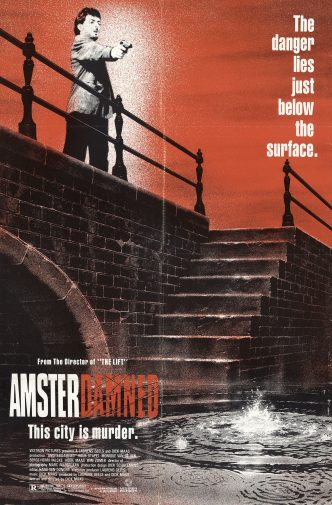

No list of Dutch horror movies would be complete without at least one by Dick Maas, who after Verhoeven is Holland’s  most important purveyor of genre fare. Maas’s first major success was 1983’s inexplicably well received THE LIFT/DER LIFE, a film whose allure I’ve never been able to fathom. His 1988 follow-up AMSTERDAMNED is much better, a three-in-one blast of horror, mystery and action that also functions as a cockeyed Amsterdam travelogue.

most important purveyor of genre fare. Maas’s first major success was 1983’s inexplicably well received THE LIFT/DER LIFE, a film whose allure I’ve never been able to fathom. His 1988 follow-up AMSTERDAMNED is much better, a three-in-one blast of horror, mystery and action that also functions as a cockeyed Amsterdam travelogue.

Huub Stapel stars as a police detective investigating a series of killings around the canals of Amsterdam that appear to have been committed by a sea monster. In fact the murders, as is revealed early on, are the work of a deranged diver who periodically surfaces in search of fresh victims. This entails a number of creative killings and an inspired bit of grotesquerie, in which a bloody corpse hanging from a bridge is dragged over a boat’s glass top. Also featured is a brilliantly staged car-motorcycle chase around the canals and an even stronger motorboat pursuit through those canals.

The double twist ending is admittedly a bit of a let-down, but the film overall registers as, simply, a damn good time. It’s certainly far removed from the stuffy art film aesthetic of most eighties-era Dutch films, and in this case that turned out to be a very good thing indeed.

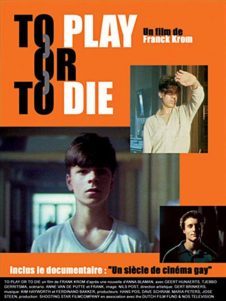

The 1990s marked something of a watershed for Dutch horror, giving us Rudolph van den Berg’s THE JOHNSONS (1992) and the hour long mini-feature NECROPHOBIA (1995). Neither, I’d argue, added up to much (although both films have their defenders), yet there was one highly unique Netherlands horror-fest that had plenty to offer: 1990’s TO PLAY OR TO DIE [SPELEN OF STERVEN], a pungent portrayal of thwarted romance made by Frank Krom, a former assistant to Mr. Verhoeven. Running just 48 minutes (not an uncommon runtime for Dutch genre films of the late eighties and early nineties), it admittedly starts off like a typical adolescent whine fest of the type that pack the Sundance Film Festival each year, but ultimately resolves itself into something far darker and more intriguing.

The 1990s marked something of a watershed for Dutch horror, giving us Rudolph van den Berg’s THE JOHNSONS (1992) and the hour long mini-feature NECROPHOBIA (1995). Neither, I’d argue, added up to much (although both films have their defenders), yet there was one highly unique Netherlands horror-fest that had plenty to offer: 1990’s TO PLAY OR TO DIE [SPELEN OF STERVEN], a pungent portrayal of thwarted romance made by Frank Krom, a former assistant to Mr. Verhoeven. Running just 48 minutes (not an uncommon runtime for Dutch genre films of the late eighties and early nineties), it admittedly starts off like a typical adolescent whine fest of the type that pack the Sundance Film Festival each year, but ultimately resolves itself into something far darker and more intriguing.

After getting humiliated in his school gym for being gay, the young Gees (Geert Hunaerts) invites one of the tormentors to his house after his parents leave town. Kees is hoping to exact revenge, and some sex, but gets far more than he bargained for when his would-be victim turns out to be smarter than expected.

So far so standard, but then in the final reel the film takes an unexpected dive into Kees’ disturbed psyche, with an increasingly surreal veneer that calls into question the reality of all that came before. It all adds up to a troubling yet compelling concoction that’s harsh, intelligent and thoroughly unpredictable.

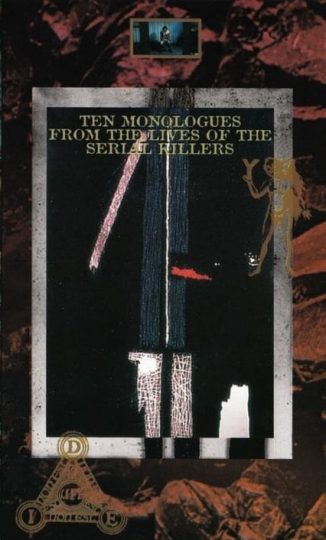

TEN MONOLOGUES FROM THE LIVES OF THE SERIAL KILLERS hails from the South African born, Netherlands  based underground filmmaker Aryan Kaganof, back when he was known as Ian Kerkhof. It’s a 1994 “documentary” about serial killers that mixes actual confessions by Ed Kemper, Ted Bundy and Kenneth Bianchi with fictional texts by J.G. Ballard and Roberta Lannes, as well as a diary entry by Henry Rollins and a monologue by Charles Manson. The confessions are presented in the form of mini-movies, with imagery that includes grainy home movie footage, videotaped confessions and a bizarre bit in which Kaganof/Kerkhof himself is seen stark naked, masturbating ecstatically while images of a bound woman are projected on his body.

based underground filmmaker Aryan Kaganof, back when he was known as Ian Kerkhof. It’s a 1994 “documentary” about serial killers that mixes actual confessions by Ed Kemper, Ted Bundy and Kenneth Bianchi with fictional texts by J.G. Ballard and Roberta Lannes, as well as a diary entry by Henry Rollins and a monologue by Charles Manson. The confessions are presented in the form of mini-movies, with imagery that includes grainy home movie footage, videotaped confessions and a bizarre bit in which Kaganof/Kerkhof himself is seen stark naked, masturbating ecstatically while images of a bound woman are projected on his body.

As a study of mass murder the film, contrary to its title, doesn’t offer much in the way of insight or methodology. Killing is only mentioned in a few of the monologues—which, for that matter, aren’t always monologues, as one of them consists of snippets from an interview, one is a diary entry and one is a rap song. Yet it all comes together into a highly singular depiction of dissociation and psychosis that does a far better job of illuminating the mindsets of those individuals who commit horrific acts than any number of more conventional serial killer dramas (of which in the 1990s there were quite a few).

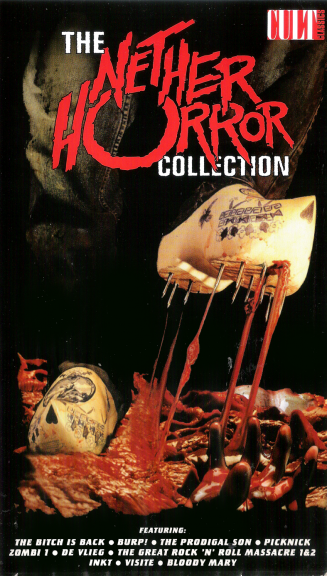

We’ll conclude this survey not with a feature but an anthology: THE NETHER HORROR COLLECTION, a two hour compilation of horror-themed shorts emerging from the Dutch underground. Released on VHS in 1996 (and now something of a collector’s item), it’s not perfect, but contains enough good stuff to warrant a solid recommendation.

One standout short is the first, 1995’s black humored “The Bitch is Back,” about a sex doll that comes to life and attacks its lay-about owner while quoting lines from famous movies. 1986’s “Burp!” is notable for some striking images, including a phone transforming into a huge mouth with rows of sharp teeth. I also appreciated 1985’s “De Vlieg,” a minimalistic depiction of a fly that won’t die, and 1992’s “Bloody Mary,” which dramatizes the twisted dynamic between a scary dude in a bar and the mousey woman bartender, a dynamic that ultimately reverses itself mightily.

One standout short is the first, 1995’s black humored “The Bitch is Back,” about a sex doll that comes to life and attacks its lay-about owner while quoting lines from famous movies. 1986’s “Burp!” is notable for some striking images, including a phone transforming into a huge mouth with rows of sharp teeth. I also appreciated 1985’s “De Vlieg,” a minimalistic depiction of a fly that won’t die, and 1992’s “Bloody Mary,” which dramatizes the twisted dynamic between a scary dude in a bar and the mousey woman bartender, a dynamic that ultimately reverses itself mightily.

I’ll be nice and refrain from discussing those shorts I didn’t care for (such as the overlong “Prodigal Son” from 1995 and the Dick Maas directed “Picknick” from ‘77). Luckily this collection, being extant on VHS (and now YouTube), can be fast-forwarded at will.

Further Dutch horror films have been made in the years since the release of the NETHER HORROR COLLECTION, including several from Dick Maas: THE SHAFT (remade from THE LIFT), SINT and PREY. None, however, have come close to replicating the impact of the preceding five titles, which may not be perfect, but are essential.