“I don’t believe in a god, but karma, whatever that is, is out there to get me.” So claims filmmaker Terry Gilliam, a longtime hero of mine due to the whimsical brilliance and epic heft of his films, along with his near-inhuman resiliency in the face of what (as we’ll see) have been some pretty formidable obstacles. I also enjoy his outspoken demeanor, which has been as much of a hindrance to Gilliam’s career as his disaster-packed shoots.

The man has no filter, and is given to public antics like taking out a full page ad in VARIETY asking Universal President Sid Sheinberg “When are you going to release my film BRAZIL?” and burning his WGA card because he was unhappy with the allocation of screenwriting credits on FEAR AND LOATHING IN LAS VEGAS (1998). As you might guess, Gilliam hasn’t fared too well in the #MeToo era, having blithely shot off his mouth and inspired plenty of contrived outrage (fact: if you’re expecting brevity and/or sensitivity from Terry Gilliam you’re barking up the wrong tree).

FEAR AND LOATHING IN LAS VEGAS (1998) Trailer

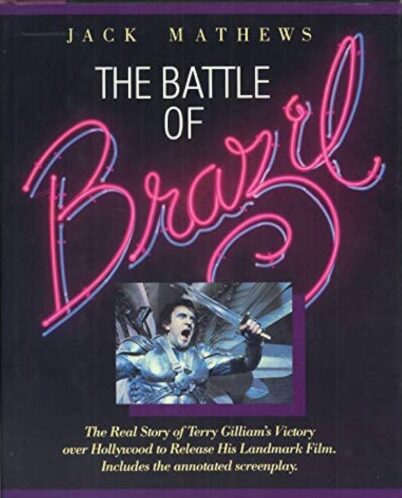

It’s no surprise that the books and films about Terry Gilliam tend to be every bit as entertaining as the films he makes. The first such example was THE BATTLE OF BRAZIL (1987) by the late LA film critic Jack Mathews (1939-2020).

BRAZIL (1985), one of Gilliam’s signature achievements, was his third solo directorial effort. It followed JABBERWOCKY (1977) and TIME BANDITS (1981), at which time Gilliam was already making enemies—note the song that plays over TIME BANDITS’ end credits, written and sung by the film’s executive producer George Harrison, who used it to air his frustrations with Gilliam (note the lyric about “The taking of time,” and another about how “All you owe is apologies”). On BRAZIL, a Universal production, Gilliam’s bridge-burning tendencies went into overdrive.

TIME BANDITS (1981) Trailer

BRAZIL (1985) Trailer

See also: GILLIAMESQUE

In THE BATTLE OF BRAZIL Mathews chronicles the conception of BRAZIL, its production and, most importantly, its aftermath. Involved was a fight between Gilliam and Sid Sheinberg, the chairman of “Hollywood’s busiest and most systematically controlled studio” (meaning it was just like the rigidly controlled world depicted in the film). Sheinberg was determined to recut the film, to which Gilliam is quoted as replying “Before that happens, I’ll burn the negative and the Black Tower” (referring to Universal’s headquarters). Employed in the battle were Gilliam’s aforementioned VARIETY add and several non-studio authorized screenings for powerful film critics, with Sheinberg giving in and releasing a Gilliam approved cut only after the film was given top awards by the Los Angeles Film Critics’ Association.

Included in THE BATTLE OF BRAZIL is BRAZIL’s screenplay, written by Gilliam, Charles McKeown, and the legendary playwright Tom Stoppard (who upon learning his work was being rewritten reportedly sent Gilliam a letter asking “Who is Charles McKeown? And what have I ever done to him?”), but the book is worth reading solely for the details on the Gilliam-Sheinberg fight. Mathews later put together a documentary for the 1999 Criterion BRAZIL DVD in which the claims made in his text are presented via interviews both new and archival, but the book is more worthy of your time. It contains a scrupulous depiction of Hollywood politicking that places it in the company of INDECENT EXPOSURE by David McClintick and OUTRAGEOUS CONDUCT by Stephen Farber and Marc Green. (There also exists a more conventional making-of doco from 1985, the 30-minute WHAT IS BRAZIL?, which is witty and informative but not especially deep or resonant.)

WHAT IS BRAZIL? (1985, Documentary)

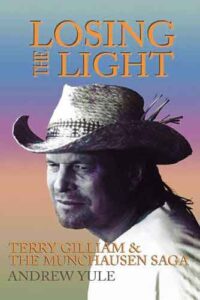

LOSING THE LIGHT (1991) by Andrew Yule chronicled the filming of Gilliam’s post-BRAZIL effort THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN (1988), a lavish fantasy whose production was downright nightmarish. Dispensing entirely with journalistic objectivity, Yule states upfront that “If Terry Gilliam’s THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN proves to be a lasting masterpiece, as some contend, it will be against all conceivable odds.”

The problems included a publicity-happy producer with whom Gilliam didn’t get along, stampeding elephants wreaking havoc, a corrupt Italian crew who all seemed to have their own side-deals and a myriad of assorted catastrophes, most notably a scene in a water tank involving explosions and a rampaging horse. The ultimate disaster, however, occurred after filming was complete, when Columbia elected to release the finished product with little-to-no publicity, resulting in one of the decade’s hoariest flops.

Yule relates this calamitous saga in a highly engaging, straightforward manner. Again, he makes no bones about the fact that MUNCHAUSEN was “the ultimate movie to avoid,” and if the revelations contained here are to be believed (and I have yet to find any reason why they shouldn’t) it was indeed the most disastrous of all Gilliam’s productions—quite a claim!

The next major example of Gilliam-centered media was the 86 minute HAMSTER FACTOR AND OTHER TALES OF THE TWELVE MONKEYS (1996), about the making of Gilliam’s 1995 film TWELVE MONKEYS. THE HAMSTER FACTOR, the first in a trilogy of Gilliam documentaries by Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe, wound up as an extra on the TWELVE MONKEYS DVD (and, later, Blu-ray) but deserves special consideration.

The film admittedly starts off like a standard “making of” promo piece, but the increasingly negative slant taken by its directors sets it apart. We’re shown a frustrated Gilliam ranting and raving (a familiar sight in Gilliam docs), arguing with star Bruce Willis and producer Charles Roven, and at one point locking himself in his trailer. We see the turmoil that erupts when the child actor cast in a pivotal role can’t hack it and Gilliam is forced to make a last minute casting change, while he crew is driven to near-madness by Gilliam’s focus on tiny details, such as a hamster in the background of one scene (hence the title).

What really sets THE HAMSTER FACTOR apart is its depiction of something I don’t believe any other movie doco has shown: the distribution process, which entails Gilliam flipping through the film’s print reviews (calling one reviewer a “bitch”) and meeting with Universal’s publicity department to look over poster designs. Most intriguing of all, we get to look in on the test screening process, where randomly recruited audiences are herded into a screening of the film and then fill out cards detailing their responses. The reactions to TWELVE MONKEYS were mostly negative, but that didn’t stop it from going on to make a great deal of money, proving the test screening process isn’t as reliable as Hollywood likes to believe.

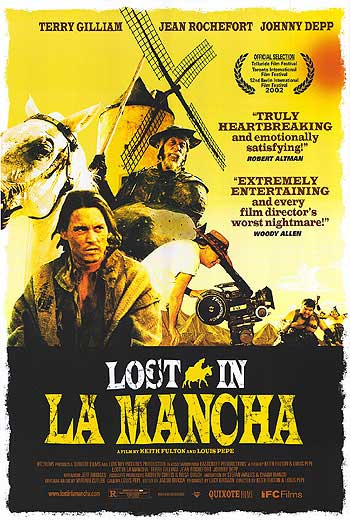

Fulton and Pepe subsequently delivered LOST IN LA MANCHA (2002), another sinfully engaging doco, this one about Gilliam’s initial attempt at making THE MAN WHO KILLED DON QUIXOTE. Johnny Depp was the star, and the veteran French thespian Jean Rochefort set to play Quixote in what appeared to be shaping as a quintessentially Gilliamesque concoction.

LOST IN LA MANCHA, decked out with animated transitions and suffused with a tartly sarcastic tone, depicts a production that was out of control from the start. The actors’ busy schedules gave Gilliam and his collaborators little-to-no latitude, and their budget was (surprise!) woefully inadequate. On location in the Spanish desert every conceivable thing that could go wrong did (cinematographer Nicola Pecorini claimed “I’ve never, never, never seen such a sum of bad luck”), with the production shut down a mere week into shooting due to a hernia suffered by Rochefort.

Gilliam did eventually make THE MAN WHO KILLED DON QUIXOTE, and Fulton and Pepe were there to document the process, but before that there was GETTING GILLIAM (2005), a documentary on the making of Gilliam’s TIDELAND (2005) by CUBE’s Vincenzo Natali. This 45-minute film, alas, turned out to be far less than one might hope for given Natali’s enormous talent and the unfettered personality of his subject.

Unlike the Fulton-Pepe films, GETTING GILLIAM feels quite perfunctory, and contains an overabundance of background info on Gilliam (which anyone even remotely familiar with the man’s work will already know). Natali also includes several animated segues that were obviously inspired by those of LOST IN LA MANCHA.

The film’s best parts show Gilliam on set, stressing out over the production, putting down director Roland Emmerich and freaking out over George W. Bush’s 2004 reelection. Equally intriguing is the DVD audio commentary by Gilliam and Natali, in which Gilliam goes into detail about his Herculean struggles to get TIDELAND into theaters, things GETTING GILLIAM doesn’t cover.

Onto HE DREAMS OF GIANTS (2019), the film that closed out Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe’s trilogy of Terry Gilliam documentaries. Whereas LOST IN LA MANCHA documented Gilliam’s doomed attempt at mounting THE MAN WHO KILLED DON QUIXOTE, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS depicts the eventual completion of that opus, helmed by a much older, wearier Gilliam than the spry fellow seen in the earlier film.

HE DREAMS OF GIANTS (2019, Documentary) Trailer

The Gilliam on display here is beset with health problems, and seems far crankier and more short-tempered than he did previously. Yet he soldiers on, and eventually completes filming, which Fulton and Pepe regard as a monumental feat. Artistically speaking, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS isn’t its makers’ most varied or stylish effort (the animated segues of their earlier work are nowhere to be found), with scenes from 8½ (1963) by Gilliam favorite Federico Fellini included to illustrate the pressures under which he labored.

Ultimately HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is compelling for reasons its makers couldn’t possibly have foreseen: it’s a true anatomy of disaster, showing that despite a director’s best efforts calamity is never far from the fore (with THE MAN WHO KILLED DON QUIXOTE being, I’m sorry to say, one of Gilliam’s worst efforts). For Gilliam calamity appears to have become the inescapable norm, meaning that at the very least more entertaining behind-the-scenes exposes will likely be forthcoming.