Dante Aligheri’s INFERNO is the first and most famous portion of his three-part 14th Century epic poem THE DIVINE COMEDY. Relating Dante’s allegorical journey through a minutely described nine-layered hell, the INFERNO has always lent itself well to visual interpretation: William Blake illustrated several passages of the poem prior to his death in 1827, and Gustave Dore’s more extensive 1860s woodcut illustrations are nearly as revered as the text itself. Filmmakers, meanwhile, have been fascinated by the INFERNO since the earliest days of the medium.

allegorical journey through a minutely described nine-layered hell, the INFERNO has always lent itself well to visual interpretation: William Blake illustrated several passages of the poem prior to his death in 1827, and Gustave Dore’s more extensive 1860s woodcut illustrations are nearly as revered as the text itself. Filmmakers, meanwhile, have been fascinated by the INFERNO since the earliest days of the medium.

The premiere (and probably best) film adaptation of Dante’s INFERNO is 1911’s L’INFERNO, the first-ever Italian feature. Further adaptations include the in-name-only 1924 Hollywood feature DANTE’S INFERNO, the equally loose 1925 Italian adaptation MACISTE IN HELL, and the 1935 Spencer Tracey headlined remake of the former film, as well as a 2007 animated feature, a 2010 action-adventure video game version and the latter’s animated DVD spin-off.

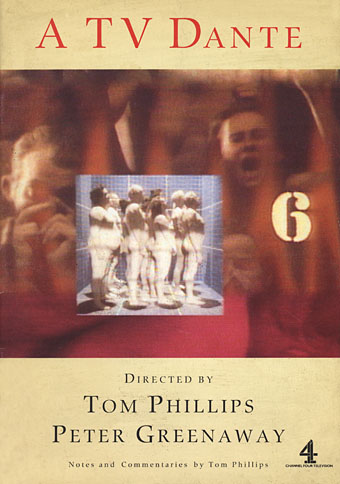

Then there was the television arena, which gave us the 1974 Hungarian TV movie POKOL-INFERNO and, more significantly, A TV DANTE: THE INFERNO. The latter was a highly ambitious undertaking by Britain’s channel four. No less than five top directors—Peter Greenaway, Raul Ruiz, Terry Gilliam, Zbigniew Rybczynski and Nagisa Oshima—were attached, each charged with adapting a block of the INFERNO’S 34 cantos. The first portion, comprising cantos 1-8, was directed by Peter Greenaway in collaboration with composer and artist Tom Phillips (whose English translation of Dante’s INFERNO was utilized) in 1989, and the second, comprising cantos 9-14, by Raul Ruiz in 1991. The remaining portions, alas, never made it to production.

Of A TV DANTE’S two parts, Greenaway and Phillips’ is by far the most significant. It was broadcast on European television in eight ten minute increments in 1990, released on VHS in the UK in ‘93, and won the Prix Italia Special Prize for the Arts. It even made it to DVD in 2011.

I feel Greenaway and Phillips’ cantos are among the most innovative, mind-expanding work ever created for television. Greenaway and Phillips give us a literal rendition of the Inferno’s horrors, together with a sub-textual thesis on Dante’s background. This is accomplished in multi-layered fashion, with the text intoned by actor Bob Peck as Dante, joined by John Gielgud as his guide Virgil and Joanne Whalley as Dante’s muse Beatrice.

Also competing for our attention are a wealth of digitally enhanced images of naked extras writhing in torment, overlaid with historical commentary from the likes of documentarian David Attenborough, classicist David Rudkin, astronomer Olaf Pederssen and Tom Phillips himself, as well as documentary footage and (then) state-of-the-art video effects in a fashion that scandalized many viewers (an imdb user whined that the program “violates cinematic grammar”).

For the rest of us, however, this 89 minute video funhouse is a wonder to behold, an exhilarating celebration of Dante’s masterpiece as well as a sly refutation of it (the historical commentators aren’t shy about criticizing Dante’s none-too-enlightened attitudes about women and unbaptized children). It’s not unlike Greenaway’s 1991 feature PROSPERO’S BOOKS, with its dense multi-layered imagery and the presence of John Gielgud in a lead role, but these cantos have a lively energy that PROSPERO lacks, being darkly comical, repellant, educational, ambiguous and never boring.

Onto the Raul Ruiz helmed cantos 9-14, which are quite different in form and style. Their reception was likewise extremely divergent from that of their justly celebrated predecessors: to date, Ruiz’s TV DANTE episodes have never been broadcast on TV or released on video in Europe or the US (although they were televised in Latin America), having been heavily criticized and claimed by some to be the primary reason the project was discontinued.

Ruiz uses Dante’s text, narrated by John Gielgud, as an ironic counterpoint to his real intent: a trenchant portrait of Chile, a country Ruiz fled in the 1970s. Thus we hear Dante’s descriptions of the fields of Hell intoned over panoramic shots of the Chilean countryside, and see Dante (Francisco Reyes) wandering through a “Hell” of Chilean villages and graveyards. The effect, unfortunately, isn’t nearly as clever or revelatory as it could have been. Ruiz admittedly made his films extremely quickly and didn’t always bother viewing their final cuts, and the wildly inconsistent, rather perfunctory filmmaking on display here evinces that sense of undue haste.

Ruiz uses Dante’s text, narrated by John Gielgud, as an ironic counterpoint to his real intent: a trenchant portrait of Chile, a country Ruiz fled in the 1970s. Thus we hear Dante’s descriptions of the fields of Hell intoned over panoramic shots of the Chilean countryside, and see Dante (Francisco Reyes) wandering through a “Hell” of Chilean villages and graveyards. The effect, unfortunately, isn’t nearly as clever or revelatory as it could have been. Ruiz admittedly made his films extremely quickly and didn’t always bother viewing their final cuts, and the wildly inconsistent, rather perfunctory filmmaking on display here evinces that sense of undue haste.

Ruiz does at least impart quite a few arrestingly gruesome and surreal images, from a man expelling liquid through a torn-up throat to a brain cordoned off by tiny flags and a pile of plucked eyeballs turned into sugary delicacies. Yet in contrast to Greenaway and Phillips’ exhilarating triumph, Raul’s episodes, intermittently striking though they may be, are a massive letdown, closing out this monumental project on a weak note. Dante, and A TV DANTE, both deserve much better.