Back in 1983 the late Lawrence Durrell predicted that the French horror writer Claude Seignolle “will draw a large audience in the United States and that his place in literature eventually will be as assured as Ambrose Bierce’s is today.” Obviously that forecast has yet to bear fruit, but Durrell’s estimation of Seignolle’s importance is, I believe, entirely correct.

At present Claude Seignolle is 95 years old. His lifelong interest in legend and superstition is on display in his many scholarly books on the subject, and also his fictional output, which is voluminous enough that when collected in 1976 it filled 23 volumes. So revered is Seignolle’s writing in his native France that in 2004 a literary prize bearing his name was established for works relating to French folklore.

In the English speaking world, alas, Seignolle is barely known. English translations of his fiction are limited to a whopping four books, all of which are quite short. Nonetheless, three of those books are must-reads, providing us with a potent taste of the work of one of the world’s foremost masters of the macabre.

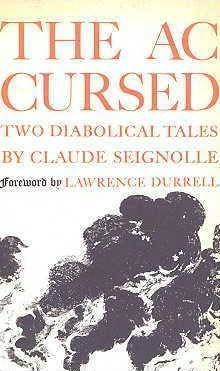

THE ACCURSED appeared in 1967 from Coward-McCann. It consists of two longish stories that, like much of Seignolle’s fiction, are situated in rural France and directly inspired by European folklore. Also in keeping with Seignolle’s oeuvre, the prose is highly poetic and often surreal in nature, yet still intellectually grounded and dramatic.

“Malvenue,” the first and longest of THE ACCURSED’S contents, concerns the sixteen year old Jeanne, a.k.a. Malvenue, who upon unearthing an ancient stone head develops an overpowering desire to commit evil acts. A lengthy flashback relates how the head was previously unearthed decades earlier by the farmer Moarc’h, and how it brought all manner of misfortune to Moarc’h and his wife Henriette—who happens to be Jeanne’s mother.

“Marie the Wolf” again concerns a naïve farm girl beset by a horrific curse. Eighteen year old Marie has an ominous wolf-like manner, bequeathed by a mysterious wolf-herder who visited her home when Marie was a little girl and placed her hand in a wolf cub’s mouth. This, the wolf-herder claimed, gave Marie the power to understand wolves and cure their bites–but only until the wolf-herder dies, at which point Marie’s powers will cease.

There’s far more to these tales than the above summaries indicate, as both are triumphs of invention and erudition, satisfying as provocative accounts of rural superstition and elegantly crafted scary stories.

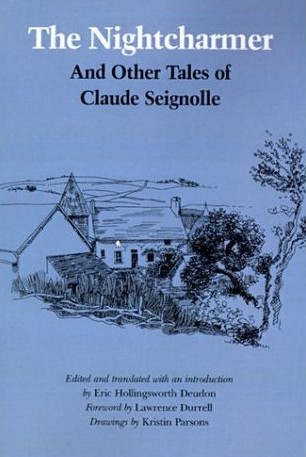

THE NIGHTCHARMER AND OTHER TALES appeared in 1983 from Texas A&M University Press. Containing just eight stories spread over 112 pages, it could have stood to be a lot longer, but is otherwise a superlative collection. Ably translated by Eric Hollingsworth Deudon, THE NIGHTCHARMER provides an excellent introduction to Seignolle’s peculiar universe, where (as in the previous book) rustic folklore and surreal terror hold sway.

The title piece is a particular standout, depicting a mythical bird who haunts the dreams of the protagonist. Also noteworthy is the wrenching “A Dog Story,” an overpowering evocation of wartime squalor centered on a desiccated dog the unwitting narrator elects to put out of its misery, with results that are horrifying and heartbreaking in equal measure. “Starfish” is a deeply confounding piece about a disfigured movie star with a death wish, while “The Last Rites” depicts a farmer driven to madness and death by the specter of a dead nun. There’s also “Hitching A Ride,” about a man’s encounter with the grim reaper who appears in the form of a sullen hitchhiker, and the book’s novella length centerpiece “The Outlander,” in which the Devil assumes the guise of a country blacksmith, and as such is unexpectedly brought down by his desire for a feeble young woman.

That last story amply demonstrates Seignolle’s audacity, and also his frank approach to sexuality, which vies with intellectual vigor and a sure grasp of supernatural apprehension.

That high point, unfortunately, was followed by 1993’s THE MAN WITH SEVEN WOLVES, the least of Seignolle’s English language books. It’s a heavily illustrated 45 page children’s book that was part of something called the “I Love to Read Collection.”

Essentially a rewrite of “Marie the Wolf” (and more likely the work of co-writer Jacqueline Kergueno than Seignolle himself), it (again) relates the story of a naïve farm girl given the power to heal wolf bites by the mysterious title character. The girl is initially outcast by her fellow villagers but, in a tacked-on and wholly unconvincing up-tempo coda, is assured by a friend that the villagers will accept her once they understand the benevolent nature of her powers. At least the copious illustrations by Philippe Fix are decent, with an appropriately quaint, minimalist hue

Claude Seignolle’s fourth and thus far final English language publication was THE BLACK CUPBOARD, which appeared in 2010 from Ex Occidente Press. It might seem like an anomaly in the Seignolle cannon with its urban setting and science fiction tinged narrative, yet, as the translator Antonio Monteiro’s learned introduction makes clear, the tale contains all of Seignolle’s trademarks: the matter-of-fact acceptance of supernatural phenomena as an integral part of everyday life, the frank (for 1958) approach to sexuality, and the classic, even mythological, themes that power the narrative. Although it’s extremely short (running a little over sixty pages), THE BLACK CUPBOARD is as rich and eventful as nearly any horror story I’ve read, juxtaposing reincarnation, a Faustian pact and a Jekyll and Hyde-like doppelganger drama.

The tale begins with the 20-year-old Philippe finding himself compelled to purchase an antique cupboard. Philippe subsequently feels the “disturbing invisible presence” of another person, and actually comes to assume the guise of a nasty old man with an identical cupboard in his house. The manner in which Seignolle alternates the two first person viewpoints, with little demarcation of any sort, is the book’s most audacious stylistic element. The old man, it seems, has sold his soul to the devil in exchange for inexhaustible sexual virility, and finds his depraved desires increasingly focused on a woman whose photo adorns his cupboard—a woman who happens to be Philippe’s girlfriend.

THE BLACK CUPBOARD is in many respects a traditional account of good and evil, yet what resonates is the overpowering air of surreal mystery. I haven’t even gone into the mysterious “other” who shadows Philippe, nor the rag-like mask found in the cupboard’s drawers, nor the perverse episode in which Philippe interacts with his cupboard in a sexually-tinged communion: “I turn off the radio and the lights…Now, in the dark, the cupboard and I have at last found again our intimacy…”

So there you have it: four books, three of them masterworks. I can only hope more English language Claude Seignolle novels and stories follow, and that this neglected genius finally assumes his rightful stature in the U.S., a recognition that is already decades overdue.