For true horror movie fans, horror moviemakers are as venerated as the films they make. And no wonder: the lives and personalities of genre auteurs like John Carpenter, George Romero, Brian DePalma, Dario Argento and others are pretty much inseparable from their art. Just check out some of the books about our horror heroes. Sure, you can log onto their respective websites, but most of those are fan run and lack the personal slant the following books—the good ones, at least—provide.

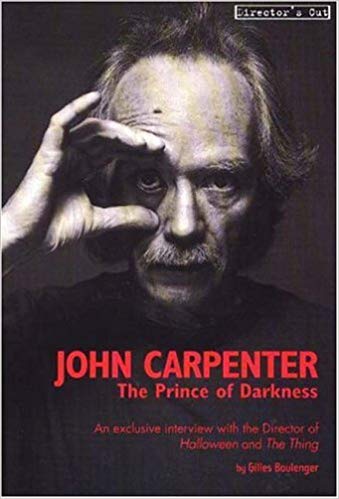

Case in point: JOHN CARPENTER, THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS, edited by Gilles Boulenger (Silman-James Press, 2003). This tome consists of a book-length interview with John Carpenter, who speaks candidly about his experiences making classics like HALLOWEEN, THE FOG, ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK and my personal favorite THE THING—whose failure at the box office nearly derailed his career. He also talks at length about growing up in the grip of the bible belt, his interest in quantum physics, and furthermore isn’t shy about discussing recent bummers like ESCAPE FROM L.A. and GHOSTS OF MARS. Carpenter comes off as a witty and intelligent man throughout and the book is compact and endlessly quotable—definitely required reading for all Carpenter fans. It’s like one of those Faber & Faber “___ on ___” interview books; editor Gilles Boulenger has compiled a number of Faber titles, and the overall layout is nearly identical.

Case in point: JOHN CARPENTER, THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS, edited by Gilles Boulenger (Silman-James Press, 2003). This tome consists of a book-length interview with John Carpenter, who speaks candidly about his experiences making classics like HALLOWEEN, THE FOG, ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK and my personal favorite THE THING—whose failure at the box office nearly derailed his career. He also talks at length about growing up in the grip of the bible belt, his interest in quantum physics, and furthermore isn’t shy about discussing recent bummers like ESCAPE FROM L.A. and GHOSTS OF MARS. Carpenter comes off as a witty and intelligent man throughout and the book is compact and endlessly quotable—definitely required reading for all Carpenter fans. It’s like one of those Faber & Faber “___ on ___” interview books; editor Gilles Boulenger has compiled a number of Faber titles, and the overall layout is nearly identical.

Speaking of Faber & Faber titles, that publisher’s LYNCH ON LYNCH (1999), which profiles David Lynch, is also a must read. Ditto Faber’s CRONENBERG ON CRONENBERG (1992), GILLIAM ON GILLIAM (1999) and BURTON ON BURTON (1995). LYNCH ON LYNCH has a great subject, obviously, who isn’t afraid to speak candidly about his obsessions…like dissecting dead fish and labeling their organs! He also discusses his films up to 1996’s LOST HIGHWAY (his apparent “comeback film” after the failure of TWIN PEAKS: FIRE WALK WITH ME); what he doesn’t talk about is how the baby from ERASERHEAD was created or his daughter Jennifer’s noxious BOXING HELENA. But my real beef is with the book’s interviewer/editor Chris Rodley, who at one point has the audacity to suggest to Lynch that the sadomasochistic relationship at the heart of BLUE VELVET should somehow be “different” so it doesn’t “reinforce those (stereotypical) images.”

What an ass. Chris, you see, is very concerned with cinematic representations of the fairer sex, and claims the response by special interest groups who protested the film “isn’t necessarily a call for censorship, but a criticism of the treatment of women in films.” Sorry Chris, but your arrogant request for “something different” does indeed smack of a “call for censorship” to me, and an extremely bone-headed one (the men in BLUE VELVET don’t exactly receive preferential treatment themselves). I commend David Lynch for restraining himself from smacking this twit upside the head (as it is, Lynch tells him to simply “Relax!”).

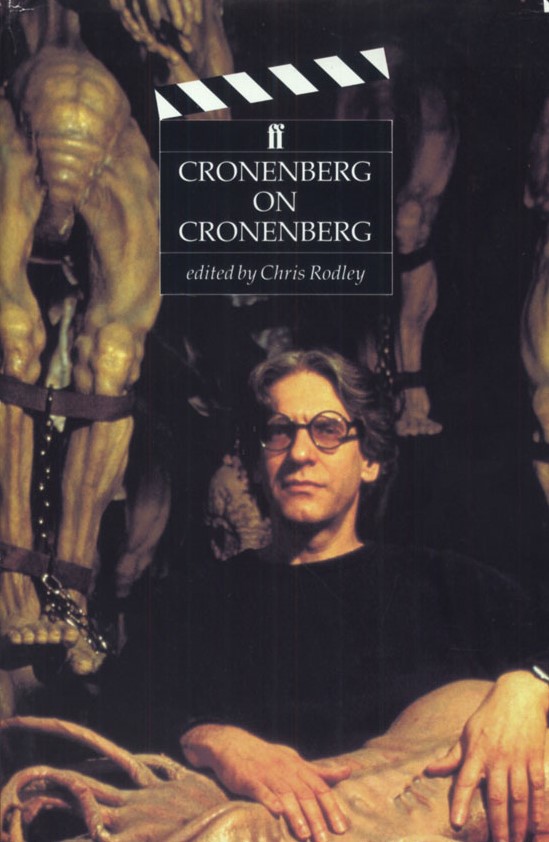

CRONENBERG ON CRONENBERG was also edited by Chris Rodley, who thankfully keeps his imbecilic views to himself this time around. The  result is the most interesting of all the Faber tomes, with “Dave Deprave” detailing his obsessions with death, disease and other fun stuff, along with his one-of-a-kind films. Unfortunately, the book only goes up to M.BUTTERFLY (my least favorite of Cronenberg’s films) and so misses out on subsequent flicks like CRASH and SPIDER, both among Cronenberg’s best work IMO. Also recommended is THE SHAPE OF RAGE: THE FILMS OF DAVID CRONENBERG, edited by Piers Handling (The Academy of Canadian Cinema; 1983). This anthology book is obviously quite dated (not to mention out of print and extremely difficult to find), but remains a vital resource for Cronenberg-philes; it includes a lengthy interview, an essay by Cronenberg dissenter Robin Wood and an interesting account of the making of VIDEODROME by Video Watchdog’s Tim Lucas.

result is the most interesting of all the Faber tomes, with “Dave Deprave” detailing his obsessions with death, disease and other fun stuff, along with his one-of-a-kind films. Unfortunately, the book only goes up to M.BUTTERFLY (my least favorite of Cronenberg’s films) and so misses out on subsequent flicks like CRASH and SPIDER, both among Cronenberg’s best work IMO. Also recommended is THE SHAPE OF RAGE: THE FILMS OF DAVID CRONENBERG, edited by Piers Handling (The Academy of Canadian Cinema; 1983). This anthology book is obviously quite dated (not to mention out of print and extremely difficult to find), but remains a vital resource for Cronenberg-philes; it includes a lengthy interview, an essay by Cronenberg dissenter Robin Wood and an interesting account of the making of VIDEODROME by Video Watchdog’s Tim Lucas.

Continuing with the Faber titles, GILLIAM ON GILLIAM, edited by Ian Christie, is another must-read, distinguished by its subject’s fearlessness. Gilliam, unlike the majority of his contemporaries, isn’t afraid to speak candidly about folks in and out of his industry, and offers some extremely frank opinions on the likes of Martin Scorsese, Gloria Steinham, Sid Sheinberg (the Universal exec who tried to recut BRAZIL) and Alex Cox (from whom Gilliam took over the production of FEAR AND LOATHING IN LAS VEGAS). Marvelously entertaining stuff.

BURTON ON BURTON, edited by Mark Salisbury, is the last of the Faber titles of direct interest to us. The subject is of course the one and only Tim Burton, of BEETLEJUICE, BATMAN and SLEEPY HOLLOW fame. Burton is—or was, at least—one of the most individual of all big studio filmmakers, and in this book he speaks bluntly about the tortured, lonely adolescence that fuelled his unique films. I’m sure quite a few of you out there can identify with him in that respect, no?

Faber books are fun, without question: lively, heavily illustrated and, best of all, none of them take more than a couple days to read. The only drawback is a crack made by filmmaker Martin Scorsese, who claimed his comments in SCORSESE ON SCORSESE (1989) were “all lies.” If that’s true then I’m hoping those “lies” were the exception and not the rule!

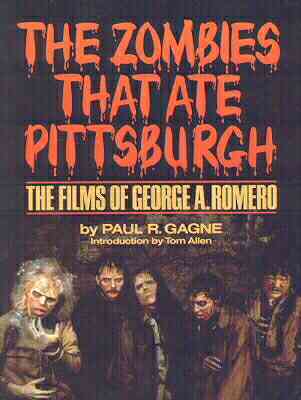

No true horror fan is entirely ignorant of the films of George Romero, and Paul Gagne’s THE ZOMBIES THAT ATE PITTSBURGH (Dodd, Mead; 1987) is an indispensable resource. A large-format paperback with in-depth chapters on all Romero’s films up to DAY OF THE DEAD (which is fine because, frankly, none of Romero’s subsequent films are worth the space), it’s heavily illustrated and quite readable. Unfortunately, it’s also long out of print.

No true horror fan is entirely ignorant of the films of George Romero, and Paul Gagne’s THE ZOMBIES THAT ATE PITTSBURGH (Dodd, Mead; 1987) is an indispensable resource. A large-format paperback with in-depth chapters on all Romero’s films up to DAY OF THE DEAD (which is fine because, frankly, none of Romero’s subsequent films are worth the space), it’s heavily illustrated and quite readable. Unfortunately, it’s also long out of print.

Another out of print book you need is THE DePALMA CUT by Laurent Bouzereau (Dembner Books; 1988). The author is obviously a Brian DePalma fanatic, and spends much of the book defending his idol against the many charges—misogyny, plagiarism, etc.—that have haunted him over the years. In all frankness, the book isn’t terribly well written, as Bouzereau’s real talents clearly lie elsewhere; he now compiles supplementary DVD material for the likes of Steven Spielberg and, of course, Brian DePalma. In any event, THE DePALMA CUT is still a must-have, as, aside from Julie Salamon’s infamous THE DEVIL’S CANDY (about the unmaking of THE BONFIRE OF THE VANITIES), it’s the only worthwhile book on its subject. This means you should skip Susan Dworkin’s DOUBLE DePALMA (Newmarket Press; 1984), a perfunctory account of the production of BODY DOUBLE. There are a few interesting behind-the-scenes tidbits, but Dworkin lets her radical feminist leanings and obvious dislike of DePalma overwhelm her book.

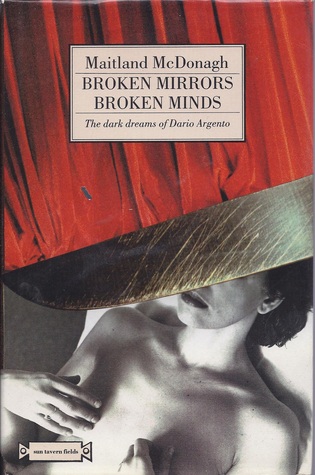

Look folks: if you’re concerned about political correctness then you’re probably better off not viewing horror movies, much less writing about ‘em.  Thankfully, Maitland McDonagh, author of BROKEN MIRRORS, BROKEN MINDS: THE DARK DREAMS OF DARIO ARGENTO (Sun Tavern Fields; 1991), has no such agenda. Argento’s films, after all, are unapologetically violent, with women getting the brunt of the abuse. This doesn’t deter McDonagh from analyzing Argento’s work in a serious, refreshingly non-PC light; I don’t agree with all her views (she claims SUSPERIA and INFERNO, my favorite Argento films, “operate on a far shallower level than the films that couch them…they are simply dark magical mystery tours…”), but I do admire the way in which they’re presented. This is, FYI, probably the most collectible of all the books mentioned herein. Seriously: used copies on Bookfinder.com sell for around two to three hundred bucks apiece…so if you ever get a chance to own this book, I’d advise jumping on it ASAP! McDonagh is also the author of FILMMAKING ON THE FRINGE: THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE DEVIANT DIRECTORS (Carol Publishing Group; 1994), a book of decent interviews with filmmakers like Stuart Gordon, Charles Band, Sam Raimi and Joe Dante.

Thankfully, Maitland McDonagh, author of BROKEN MIRRORS, BROKEN MINDS: THE DARK DREAMS OF DARIO ARGENTO (Sun Tavern Fields; 1991), has no such agenda. Argento’s films, after all, are unapologetically violent, with women getting the brunt of the abuse. This doesn’t deter McDonagh from analyzing Argento’s work in a serious, refreshingly non-PC light; I don’t agree with all her views (she claims SUSPERIA and INFERNO, my favorite Argento films, “operate on a far shallower level than the films that couch them…they are simply dark magical mystery tours…”), but I do admire the way in which they’re presented. This is, FYI, probably the most collectible of all the books mentioned herein. Seriously: used copies on Bookfinder.com sell for around two to three hundred bucks apiece…so if you ever get a chance to own this book, I’d advise jumping on it ASAP! McDonagh is also the author of FILMMAKING ON THE FRINGE: THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE DEVIANT DIRECTORS (Carol Publishing Group; 1994), a book of decent interviews with filmmakers like Stuart Gordon, Charles Band, Sam Raimi and Joe Dante.

Director William Friedkin may be best known for more-or-less mainstream thrillers like THE FRENCH CONNECTION and THE RULES OF ENGAGMENT, but he also made THE EXORCIST, one of the most potent horror movies of all time, as well as THE GUARDIAN, which falls at the opposite end of the genre spectrum. About this madman, who in his heyday apparently made Oliver Stone look like Pat Robertson, I recommend two books: the biographical HURRICANE BILLY by Nat Segaloff (Morrow/Avon; 1990) and the more scholarly WILLIAM FRIEDKIN: FILMS OF ABERRATION, OBSESSION AND REALITY by Thomas D. Clagett (Silman-James Press; 2003).

Of the two, Segaloff’s book is the more accessible. Segaloff writes about Friedkin’s work with an irrepressible fanboyish enthusiasm, yet isn’t shy in confronting his subject’s oft-outrageous antics. Clagett’s textbook-like tome, on the other hand, is much heavier going (in its updated second edition, at least); it’s over 400 pages of densely worded, highly academic prose. It is, however, worth perusing for serious Friedkin buffs (like myself), as the author has quite a few insights into his subject’s work.

Speaking of madmen, I think everyone should read at least one book on Roman Polanski, one of the world’s foremost cinematic provocateurs (onscreen and off), who’s led a wide-ranging, event-filled life that’s every bit as interesting as his films. I’ve read four books on the man, of varying quality. Thomas Kieran’s ROMAN POLANSKI STORY (Grove Press; 1980) is pure sleaze, having been penned shortly after Polanski’s 1976 arrest for molesting a thirteen-year-old girl in Jack Nicholson’s hot tub and subsequent flight from justice. Kieran’s sensationalistic, poorly written account is filled with salacious details, and not a few outright lies. Barbara Leaming’s more thoughtful and psychoanalytic POLANSKI: THE FILMMAKER AS VOYEUR (Simon and Schuster; 1983) is too short to do its subject justice, although it’s definitely preferable to the former book. Polanski’s 1983 autobiography ROMAN (William Morrow; 1984) is likewise pretty disappointing, being a heavily ghosted account that goes out of its way to whitewash Polanski’s many outrages and make him seem like a decent guy; the result is compelling, but also whiny, affected and rather dull.

Speaking of madmen, I think everyone should read at least one book on Roman Polanski, one of the world’s foremost cinematic provocateurs (onscreen and off), who’s led a wide-ranging, event-filled life that’s every bit as interesting as his films. I’ve read four books on the man, of varying quality. Thomas Kieran’s ROMAN POLANSKI STORY (Grove Press; 1980) is pure sleaze, having been penned shortly after Polanski’s 1976 arrest for molesting a thirteen-year-old girl in Jack Nicholson’s hot tub and subsequent flight from justice. Kieran’s sensationalistic, poorly written account is filled with salacious details, and not a few outright lies. Barbara Leaming’s more thoughtful and psychoanalytic POLANSKI: THE FILMMAKER AS VOYEUR (Simon and Schuster; 1983) is too short to do its subject justice, although it’s definitely preferable to the former book. Polanski’s 1983 autobiography ROMAN (William Morrow; 1984) is likewise pretty disappointing, being a heavily ghosted account that goes out of its way to whitewash Polanski’s many outrages and make him seem like a decent guy; the result is compelling, but also whiny, affected and rather dull.

This leaves John Parker’s POLANSKI (Victor Gollancz; 1992), by far the best and most up-to-date (even if it is eleven years old now) of the Polanski bios. Parker unflinchingly details RP’s frequently repulsive behavior, but what ultimately emerges is a compelling portrait of an extremely complex individual who continues to thrive, despite having grown up amidst the horrors of Nazi rule in his native Poland, having had his first wife and unborn child brutally slaughtered by Charles Manson’s “family” in 1969, getting exiled permanently from the US for the above-mentioned sexual escapade and alienating nearly every producer he’s ever worked for (along with quite a few actors) with his irascible personality. In other words, Parker can’t help but admire Polanski’s refusal to give up, even in the face of an untiring, implacable enemy: himself.

Rob Van Scheers’ PAUL VERHOEVEN (Faber & Faber; 1997) is a solid look at another foreign immigrant who’s caused more than his share of trouble on American movie screens. Verhoeven made a number of outrageous films in his native Holland (TURKISH DELIGHT, SPETTERS, THE FOURTH MAN) and continued in that vein after relocating to Hollywood (with ROBOCOP, BASIC INSTINCT and STARSHIP TROOPERS). Van Scheers thoughtfully examines all Verhoeven’s films (even the bad ones), drawing upon extensive interviews with Verhoeven and his cohorts. If nothing else, this book warrants mention as the only print resource I know of to contain a serious, non-ironic defense of SHOWGIRLS!

One filmmaker whose works I’ve long admired is Nicolas Roeg, the iconoclastic genius behind WALKABOUT, DON’T LOOK NOW and BAD  TIMING, among many others. His films are so bizarre and complex I’m sure many books could be written on them. So far, however, only two slim volumes exist that I know of: THE FILMS OF NICOLAS ROEG by Neil Sinyard (Charles Letts; 1991) and FRAGILE GEOMETRY: THE FILMS, PHILOSOPHIES AND MISADVENTURES OF NICOLAS ROEG by Joseph Lanza (PAJ; 1989).

TIMING, among many others. His films are so bizarre and complex I’m sure many books could be written on them. So far, however, only two slim volumes exist that I know of: THE FILMS OF NICOLAS ROEG by Neil Sinyard (Charles Letts; 1991) and FRAGILE GEOMETRY: THE FILMS, PHILOSOPHIES AND MISADVENTURES OF NICOLAS ROEG by Joseph Lanza (PAJ; 1989).

Sinyard’s book is okay, with chapters analyzing each of Roeg’s films from PERFORMANCE (1970) to THE WITCHES (1990). The author’s observations are intelligent for the most part, although I find his viewpoint too conservative overall to do Roeg’s work justice. Lanza’s wildly eccentric study seems more appropriate to Nicolas Roeg’s loopy universe. In FRAGILE GEOMETRY present tense observations about Roeg’s films alternate with interviews with Roeg and his screenwriters Paul Mayersberg and Alan Scott, as well as a chapter comparing Roeg’s work—favorably—to that of Ed Wood! According to Lanza: “No other two directors have so ingeniously mastered the art of ambivalent intention by refusing to reveal whether we are really laughing at them or they at us.”

In fact, there is another director to whom the above declaration applies, perhaps even more fittingly than either Nicolas Roeg or Ed Wood. It’s Ken Russell, the British cinema’s official “wild man,” known for loopy masterpieces like THE DEVILS, TOMMY, THE LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM and GOTHIC. Like Roeg’s work, Russell’s films deserve better than they’ve been given, in print at least. The anthology KEN RUSSELL, edited by Thomas R. Atkins (Monarch Press; 1976) is a scrappy collection that’s more a pamphlet than a book. KEN RUSSELL: THE ADAPTOR AS CREATOR by Joseph Gomez (Frederick Muller Ltd.; 1976) is better: a highly literate account containing an introduction by the man himself (who calls it “the best thing ever written about me and my work and likely to remain so”). The problem is that these 27-year-old books are just too damn old, with many of Russell’s most interesting films IMO having been made in the years since their respective publications. Russell fans are probably best off reading his spirited 1989 autobiography A BRITSH PICTURE (ALTERED STATES in the US) or, better yet, listening to his peerlessly entertaining DVD commentaries.

German filmmaker Jorg Buttgereit is the demented genius behind perverted classics like NEKROMANTIK and SCHRAMM. David Kerekes’ appropriately titled SEX MURDER ART: THE FILMS OF JORG BUTTGEREIT (Headpress; 1994) is a good resource for folks interested in this unique filmmaker. Much like the aforementioned George Romero book, it’s copiously illustrated and user-friendly, with much pertinent info on the banning of NEKROMANTIK 2 in Germany. Needless to say, the book, like the films it describes, is extremely hard-core stuff and NOT for all tastes!

German filmmaker Jorg Buttgereit is the demented genius behind perverted classics like NEKROMANTIK and SCHRAMM. David Kerekes’ appropriately titled SEX MURDER ART: THE FILMS OF JORG BUTTGEREIT (Headpress; 1994) is a good resource for folks interested in this unique filmmaker. Much like the aforementioned George Romero book, it’s copiously illustrated and user-friendly, with much pertinent info on the banning of NEKROMANTIK 2 in Germany. Needless to say, the book, like the films it describes, is extremely hard-core stuff and NOT for all tastes!

Lucio Fulci is another filmmaker whose films—ZOMBIE, THE BEYOND, CITY OF THE LIVING DEAD—tend to elicit decidedly strong reactions. Chas. Balun’s LUCIO FULCI: BEYOND THE GATES (Blackest Heart Books; 1996) is hardly the definitive book on its subject, but it is a fun 76-page booklet in which Deep Red‘s Balun airs his oft-hilarious views on Fulci’s films (on THE NEW YORK RIPPER, with its quacking killer: “Why a fuckin’ duck?”). It also features a good intro by Fulci’s daughter Antonella, who writes candidly of her father’s mercurial personality (“If you wanted to live with Dad, you had to stop trying to understand him. You just had to accept him”).

Last but definitely least, we come to the infamous Ed Wood, the supposed worst filmmaker who ever lived. I can think of worse moviemakers than he, but will concede that Wood’s films, which include GLEN OR GLENDA and PLAN NINE FROM OUTER SPACE, are pretty stinky (and often damn funny!). Rudolph Grey’s A NIGHTMARE OF ECSTASY: THE LIFE AND ART OF EDWARD D. WOOD, JR. (Feral House; 1992) was the basis of Tim Burton’s 1994 EW biopic, and consists of quotations from many of Wood’s associates. That’s right, the whole book is made up of quotations, arranged in chronological order. Thus Grey can’t be accused of falsification or even bad writing: he literally lets his subjects speak for themselves. The result is a satisfying look at Wood’s unique life and films, including his final descent into alcoholism and untimely death that Tim Burton’s film ignored.

There are more such books, of course. Unfortunately, many are so rare and/or expensive as to be beyond even my grasp (Tim Lucas and Peter Blumenstock’s OBSESSION: THE FILMS OF JESS FRANCO is a tantalizing title I have yet to track down), while others I’ve simply never gotten around to reading (Stephen Thrower’s BEYOND TERROR: THE FILMS OF LUCIO FULCI falls into this category, but it is near the top of my list). Hopefully I’ll be able to update this piece before too long.

Coming soon: short reviews of single-film “making of” tomes (i.e. THE NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD FILMBOOK, THE MAKING OF THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT, etc.), autobiographies (including Lloyd Kaufman’s ALL I NEED TO KNOW I LEARNED FROM THE TOXIC AVENGER and William Castle’s essential STEP RIGHT UP: I’M GONNA SCARE THE PANTS OFF AMERICA!) and horror movie guides. Stay tuned!