On December 19, 1978 the so-called “Blood Letter from Nanhai” made its bow in the Taiwanese Central Daily News. Taking the form of an article by Zhu Gui, a Northern Taiwan based college professor, it related the finding of a blood letter, so named because it was written in blood on the insides of seashells, by a fisherman on a coral reef in the South China Sea. The story in the letter (allegedly translated from Vietnamese to Taiwanese by Gui) was told by a Vietnamese man identified as Yuan Tien Chiou who was fleeing the chaos during the Fall of Saigon.

On December 19, 1978 the so-called “Blood Letter from Nanhai” made its bow in the Taiwanese Central Daily News. Taking the form of an article by Zhu Gui, a Northern Taiwan based college professor, it related the finding of a blood letter, so named because it was written in blood on the insides of seashells, by a fisherman on a coral reef in the South China Sea. The story in the letter (allegedly translated from Vietnamese to Taiwanese by Gui) was told by a Vietnamese man identified as Yuan Tien Chiou who was fleeing the chaos during the Fall of Saigon.

The story in the letter (allegedly translated from Vietnamese to Taiwanese by Gui) was told by a Vietnamese man who was identified as Yuan Tien Chiou, fleeing the chaos during the Fall of Saigon.

Referring to the April 1975 capture of the capitol of South Vietnam by the Viet Cong, and the departure of virtually all the American military personnel that remained in the wake of the Vietnam War, the Fall of Saigon was, according to Chiou, “downhearted and mournful,” with most of his eleven family members killed. The rest were finished off on the coral reef, where they ended up facing starvation and resorting to cannibalism (“Who wants to drift to an isolated island and eat the flesh of his own son?”), with Chiou the lone survivor, lamenting his fate and raging against the “Great Ally” (the United States) responsible for plunging his country into chaos.

“Who wants to drift to an isolated island and eat the flesh of his own son?”

That, at least, is the story that was told. In the years since the end of the Cold War the Nanhai Blood Letter has been written off as a fiction created by Zhu Gui, something a careful reading should make clear (the writing is remarkably erudite for a supposedly starving man using his own blood as ink). That didn’t stop it from being widely taught in Taiwan schools and used as propaganda by the authoritarian KMT (Kuomintang) government, who were looking to whip up anti-American and anti-communist sentiment by exploiting the very real plight of the so-called “boat people” fleeing Vietnam. “Be an anti-communist fighter today or become a refugee at sea tomorrow” was the slogan concocted by the KMT. In 1979 the letter was even translated into English so that “the deplorable story will be heard not only in the Orient but also in the Occident.”

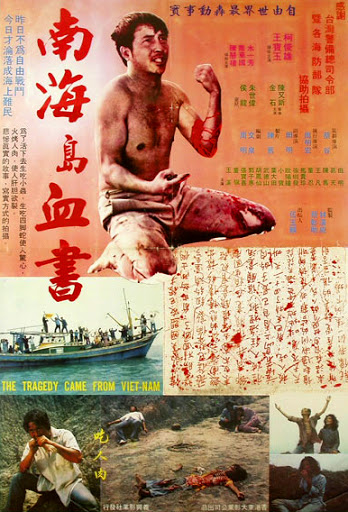

The Nanhai blood letter was also, needless to add, co-opted by the media. A Chinese language novel based on the letter, QING NIAN ZHAN SHI BAO (roughly: BLOOD AND TEARS IN THE SOUTH SEA) by Li Yuanping, was published in 1979, and a Taiwanese movie appeared that same year. NAN HAI DAO XUE SHU, the film in question, has two official English titles, THE TRAGEDY CAME FROM VIETNAM and SOUTH SEA BLOOD LETTER (which has created some confusion on the part of the imdb, which incorrectly identifies these titles as separate movies), even though it’s all-but unknown in the English speaking world. Nor, for that matter, does the film appear to have made much of an impact in its native land.

…it related the finding of a blood letter, so named because it was written in blood on the insides of seashells…

“Blood Letter from Nanhai” is largely political in nature, but the film definitely isn’t. It may contain political overtones,  as evinced by the opening scenes in which the contents of the blood letter are superimposed over documentary footage of the Vietnam War, but the majority of its attention is lavished on more exploitable elements.

as evinced by the opening scenes in which the contents of the blood letter are superimposed over documentary footage of the Vietnam War, but the majority of its attention is lavished on more exploitable elements.

The early Vietnam set scenes, marked by unflinching carnage, are among the least offensive. Things get nastier once the protagonist and his fellow refugees board the boat promising to take them to freedom, upon which they’re forced to drink their own urine to survive. The boat’s corrupt captain, meanwhile, hoards food and water, and forces the women refugees to provide sexual favors in exchange for partaking in his stash. Things degenerate entirely once the boat crashes on the coral reef, a desolate landscape where the specter of starvation quickly becomes apparent, and the protagonist’s young son provides the desired sustenance.

This is all quite powerful in a primal, gut-level manner, with impossible-to-forget images of the desperate protagonists attempting to lap up a puddle at the bottom of a hole and the stripped-clean corpse of a cannibalized young boy (featured, charmingly enough, on the poster). The film is also, alas, a bit too shrill for its own good. This is to say that the material is dramatic enough to begin with, and so doesn’t need the insistent music cues and portentous close-ups to which the directors Ku Tsai and Ming Hung Chou continually subject it.

The film’s suffocating grimness probably explains why it never got much in the way of a viewership. It certainly appeared at the right time, i.e. in the early years of the Italian cannibal movie cycle (which had turned out THE MAN FROM DEEP RIVER and JUNGLE HOLOCAUST, and a year later would reach its apotheosis with CANNIBAL HOLOCAUST), and shortly after the Mexican-made Andes crash inspired trash-fest SURVIVE! (1976).

The film’s suffocating grimness probably explains why it never got much in the way of a viewership.

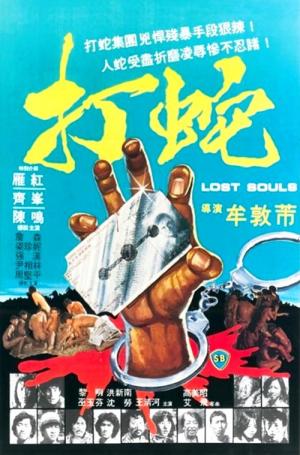

More pertinently, NAN HAI DAO XUE SHU spearheaded an East Asian refugee film craze centered in Hong Kong that capitalized on uncertainty about the 1997 Chinese takeover. As with the Taiwanese, the specter of communism was a source of great anxiety for the citizens of Hong Kong, as evinced by the 1980 Shaw Brothers production LOST SOULS/DA SE.

Its particulars may differ from those of NAN HAI DAO XUE SHU, but LOST SOULS’ style and overall tone are virtually identical, down to the newspaper clippings that open the film (in place of the blood letter text shown in NAN HAI DAO XUE SHU) and exploitation based narrative that eschews overt politics in favor of category III (i.e. adults only) outrage. The refugee protagonists of LOST SOULS aren’t Vietnamese boat people (they’re actually from China, and aren’t fleeing political oppression), and they don’t resort to cannibalism, although what they do have to contend with—beatings, burning, sexual exploitation, hanging—is just as awful.

Its particulars may differ from those of NAN HAI DAO XUE SHU, but LOST SOULS’ style and overall tone are virtually identical, down to the newspaper clippings that open the film (in place of the blood letter text shown in NAN HAI DAO XUE SHU) and exploitation based narrative that eschews overt politics in favor of category III (i.e. adults only) outrage. The refugee protagonists of LOST SOULS aren’t Vietnamese boat people (they’re actually from China, and aren’t fleeing political oppression), and they don’t resort to cannibalism, although what they do have to contend with—beatings, burning, sexual exploitation, hanging—is just as awful.

It was followed by director Ann Hui’s one-two punch of GOD OF KILLERS/THE STORY OF WOO VIET/WOO YUET DIK GOO SI in 1981 and BOAT PEOPLE/TAU BAN NO HOI in ’82. They comprise the second and third entries in Hui’s Hong Kong trilogy (with the first being the 1978 A BOY FROM VIETNAM, taken from an episode of the TV docu-series BELOW THE LION ROCK/SI JI SAN HA) that was allegedly based on stories Hui heard from actual Vietnam refugees.

GOD OF KILLERS and BOAT PEOPLE were pioneering entries in the Hong Kong Cinema New Wave, with the former marking an early starring role for the iconic Chow Yun Fat. Those familiar with Chow’s later roles in A BETTER TOMORROW, HARD BOILED et al will probably find GOD OF KILLERS slow going, as will viewers of NAN HAI DAO XUE and LOST SOULS, whose brand of fact-based exploitation was jettisoned (or at least lessened) in favor of Hui’s more thoughtful and relevant explorations of the boat people’s travails. Yes, GOD OF KILLERS and BOAT PEOPLE are Message Movies, and paved the way for later films on the subject like REFUGEE’S MELODY/TIENG SAO LY HUONG (1998) and GREEN DRAGON (2001).

Regarding the Blood Letter that spearheads this essay, it’s now a historical curiosity. NAN HAI DAO XUE, for its part, found some popularity in the 1990s greymarket VHS circuit—the Just for the Hell of It catalogue described it thusly: “A group of refugees lost and drifting in the ocean resort to urine-drinking and soon cannibalism in this bleak and unsettling Asian film,” while the Deep Red Collection stated that “boat people drink each other’s blood and urine before snarfing one another in an orgy or mondomania”—although the TRAGEDY CAME FROM VIETNAM/SOUTH SEA BLOOD LETTER title confusion was never resolved.

The 1997 Chinese handover of Hong Kong, as we all know, occurred, and, as we all know, hasn’t been without conflict. The Vietnamese boat people have had a similarly fraught history, although a few of them have gone onto greener pastures (such as the late Hiep Thi Le, a Vietnamese refugee who went on to star in Oliver Stone’s HEAVEN AND EARTH and operate two successful LA restaurants), just as NAN HAI DAO XUE has all-but completely faded from view.