Three decades ago, Jeffrey Katzenberg, head of the Walt Disney Company’s motion picture division, made a startling but not entirely unexpected decree: that Disney executives would generate movie concepts themselves. As stated in the now-legendary January 11, 1991 Katzenberg Memo that was circulated throughout the company (and, inevitably, Hollywood), “it is hard to understand how the amounts being paid for spec scripts can be justified,” and that “Creative studio executives should be in the business of developing ideas, not buying them.”

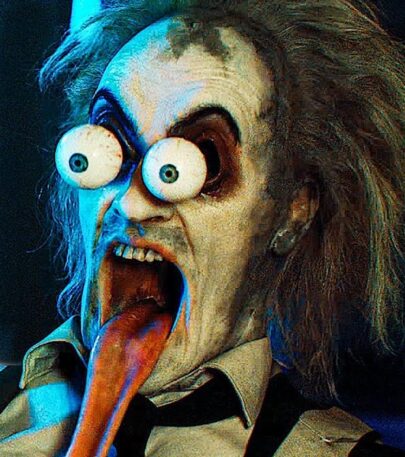

BEETLEJUICE BEETLEJUICE Trailer

To this end Katzenberg demanded that all his fellow executives come up with movie ideas, the results of which weren’t too promising. Allegedly, the best these non-writers were able to conceive was an idea about a Three Stooges-like trio of funny fellows, with characteristics and incidents to be determined. Still, the idea of Hollywood execs generating their own concepts struck (having been satirically breached in the 1992 Robert Altman film THE PLAYER), although it took until the Writer’s Guild Strike of 2007-08 to really come to fruition, and, in the words of producer Lynda Obst, “propel the new business model in the direction it was already going, just more quickly and drastically.”

It was then that, with writers sidelined, Hollywood studio execs “must have said to themselves, ‘We can generate our own material. Why not? We already know what we want’” (Obst). As we’ve already established, Hollywood suits aren’t writers, and in the post-2008 “New Abnormal” set about greenlighting what they were able to conceive: new versions of old fairy tales (SNOW WHITE AND THE HUNTSMAN, JACK THE GIANT SLAYER, HANSEL AND GRETEL: WITCH HUNTERS, MALEFICENT, etc.), remakes—sorry: reboots—and, of course, sequels. Gen-X nostalgia become Hollywood’s major driving force in the 2010s and ‘20s, which marked the rise of the legacy sequel as long-aborted follow-ups to eighties hits like TRON, BLADE RUNNER and TOP GUN saw their development paths cleared.

BEETLEJUICE (1988) marks the latest eighties favorite to get a decades-after-the-fact sequel (36 years, to be exact, the same amount of time that passed between TOP GUN and TOP GUN: MAVERICK). BEETLEJUICE BEETLEJUICE delivers most everything we’ve come to expect from a legacy sequel, bringing back much of the creative team from the original film and replicating most of the things that made it memorable, while aggressively courting younger viewers in the form of one or more up-and-coming stars.

A refresher: BEETLEJUICE was very much a product of the Old Abnormal, originating via a spec script (meaning a screenplay written without guarantee of payment) by the late Michael McDowell. Its young director Tim Burton heavily retooled the POLTERGEIST-inspired script to fit his own comedically-inclined sensibilities, and was given the latitude to do so by The Geffen Company (which also turned out eccentric releases like LOST IN AMERICA, AFTER HOURS and JOE’S APARTMENT), albeit on a modest-by-Hollywood-standards $15 million budget (equivalent to $40 million in today’s dollars).

The film transcended its limited resources through style, inspiration, a playfully macabre Danny Elfman score, a superb integration of the Harry Belafonte tunes “Day-O” and “Jump in The Line (Shake Señora)” and a design aesthetic that embraced tackiness. The sets and special effects, in other words, were supposed to look kitschy and unreal, which accorded with the budgetary limitations and audience sensibilities (as the unreality took the edge off imagery that would have probably seemed pretty disturbing). BEETLEJUICE was further illuminated by a teenaged Winona Ryder as the screen’s premiere “annoying goth girl” Lydia Deetz and Michael Keaton ad-libbing his way through the role of the troublemaking “Ghost with the Most” Betelgeuse, who had a whopping 17 minutes of screen time.

The Warner Bros. backed BEETLEJUICE BEETLEJUICE, bearing a healthy $100 million budget, brought back Burton, Elfman and several BEETLEJUICE cast members, including Keaton (who again appears for only 17 minutes), Ryder and Catherine O’Hara as Lydia’s pretentious artist mom Delia. Gone are Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis as the previous film’s ghost protagonists (because ghosts don’t age, which Baldwin and Davis most certainly have), and Jeffrey Jones as Lydia’s father Charles (because of this), who’s killed off in a plane accident early on in BEETLEJUICE BEETLEJUICE and, as with all the ghost characters herein, fully displays his means of death—meaning he spends the remainder of the film headless.

New to the franchise is Hollywood’s current It Girl (and star of the Burton-produced Netflix series WEDNESDAY) Jenna Ortega as Lydia’s daughter Astrid. It’s she who powers the narrative, with Astrid unknowingly lured into the afterlife by a wily ghost boy (Arthur Conti) looking to swap places with her, inspiring a Betelgeuse summoning by a desperate Lydia. Other newly minted cast members include Willem Dafoe as an actor-turned-afterlife detective with an exposed brain, Justin Theroux as Lydia’s shady earthbound suitor (a role that frankly isn’t necessary) and Burton’s current squeeze Monica Bellucci as Betelgeuse’s former wife, who ended up dismembered by her not-yet-deceased Hubbie.

In contrast to a previous attempt at a BEETLEJUICE sequel, whose setting was indicated by its title BEETLEJUICE GOES HAWAIIAN, BEETLEJUICE BEETLEJUICE is situated in the same mock-gothic house of the original film. Its cartoony look and tone were replicated with reasonable fidelity, as was the politically incorrect sense of humor (although in contrast to what some have been claiming, I found the supposed “envelope pushing comedy” pretty tame). Artistically, however, BEETLEJUICE BEETLEJUICE is considerably less satisfying than its predecessor.

It’s an interesting paradox of modern Hollywood that executives have asserted control over their product like never before, yet grant a remarkable amount of creative freedom to directors willing to follow the franchise dictum “The same, but different.” Burton, whose past battles with the suits are well known, followed that dictum to the letter, and experienced what he calls a creative resurgence after recent big studio disappointments like MISS PEREGRINE’S HOME FOR PECULIAR CHILDREN (2016) and DUMBO (2019). I’m glad Burton had a good time making BEETLEJUICE BEETLEJUICE, but let’s not forget Orson Welles’ claim that “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.”

Where the initial film was concise and tightly structured, this sequel feels bloated and meandering. Burton indulged himself to the fullest, revelling in elaborate stylistic flourishes (with a pivotal sequence presented in Claymation form and another in Mario Bava inspired black-and-white with Italian subtitles) and a far denser presentation of the afterlife, which in addition to the waiting room and sandworm packed desert of BEETLEJUICE includes a “soul train” that embodies its name in every respect, an office setting where Betelgeuse hangs out and quite a few cavernous rooms and hallways. The script, credited to WEDNESDAY staff writers Alfred Gough and Miles Millar and PRIDE & PREJUDICE & ZOMBIES’s Seth Grahame-Smith, follows Burton’s indulgent lead, cramming in an overabundance of subplots, superfluous characters and gratuitous shout-outs to the former film (a “Day-O” chorus at Charles’ funeral is a fun idea but makes absolutely no logical sense, even in a kitschy context).

This more-is-more approach has the unfortunate effect of spotlighting the narrative inconsistencies endemic to the material, things that weren’t too bothersome in the economical BEETLEJUICE but are impossible to ignore here. What precisely is the scope of Betelgeuse’s powers? How is it that he can possess an entire convent full of wedding guests yet can’t stop Lydia from banishing him from the mortal plain by saying his name three times? And why is he presented with a normal sized cranium when, you’ll recall, his head was shrunk down to tangerine size at the end of the previous film? The crummy CARRIE-inspired dream-shock ending is a further liability, pointing up the fact that Burton nearly always has trouble concluding his films (BEETLEJUICE, keep in mind, didn’t have a particularly satisfying fade-out, either).

Another problem: BEETLEJUICE’s participants have changed considerably in temperament and outlook. There’s Winona Ryder, who back in 1988 underplayed her role quite effectively but went the opposite route in 2024, with exaggerated facial expressions, it seems, now an integral component of her on (and off) screen shtick. Danny Elfman, in keeping with the film’s overall aesthetic, greatly extended his iconic theme, which I feel worked fine in its initial form. As for Burton, his staging is far more antic than it formerly was, and he repeats a mistake he made in BATMAN (1989) by diluting Elfman’s score with lame pop songs. The only participant who can be said to truly replicate his work in the former film is Keaton, who once again ad-libbed most of, if not all, his lines—although the character has been updated, with an impish chumminess inspired, evidently, by DEADPOOL.

Ortega is strong as Astrid, although she doesn’t resemble her “Alleged Mom” Winona Ryder in the slightest (and nor does she look at all like an Astrid). Bellucci fares equally well as Betelgeuse’s dismembered Italian-accented ex; the sight of her reattaching her severed body parts with a staple gun is one of the film’s most striking, and authentically Burtonesque, portions (it’s just too bad about the blah disco tune played over the scene).

Other striking images include Burton regular Danny DeVito as a ghost janitor getting shrunk into oblivion, peoples’ faces sucked into cell phones and Betelgeuse literally spilling his guts. There’s nothing, however, to equal the early car crash of BEETLEJUICE, in which the vehicle in question is plunged into a river after being counterweighted by a tiny dog on a wooden beam, or its climactic depiction of levitating ghosts decaying in midair.

Not that such things mattered to the greedy executives who oversaw BEETLEJUICE BEETLEJUICE. It’s a hit (in its opening weekend, at least), suggesting that the legacy sequel model is a lucrative one. Tim Burton may be experiencing a creative resurgence, but the true beneficiaries of this success are the suits who greenlit the film, proving that in many respects the situation in 1988 versus that of today is indeed the same, but different.