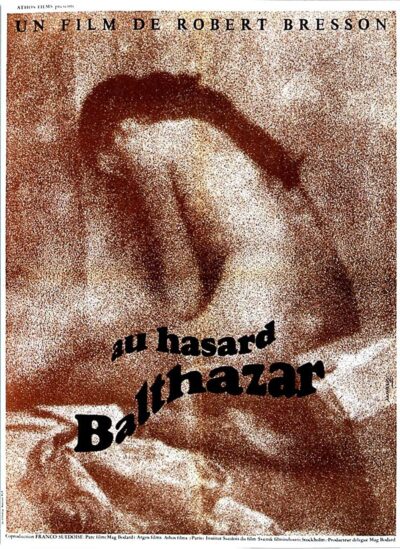

AU HASARD BALTHAZAR (1966) is one of the most fascinating films made by France’s brilliant and maddening Robert Bresson (1901-1999). The very definition of an ascetic filmmaker, Bresson was famous for the limitations he placed on himself, his collaborators and his audience. That’s an appropriate state of affairs in AU HASARD BALTHAZAR, which foregrounds a donkey, and so required an unorthodox filming approach.

AU HASARD BALTHAZAR (1966) is one of the most fascinating films made by France’s brilliant and maddening Robert Bresson (1901-1999). The very definition of an ascetic filmmaker, Bresson was famous for the limitations he placed on himself, his collaborators and his audience. That’s an appropriate state of affairs in AU HASARD BALTHAZAR, which foregrounds a donkey, and so required an unorthodox filming approach.

The animal, residing in a rural French village (actually the Guyancourt commune bordering Paris), is named Balthazar, a moniker whose Biblical roots (Saint Balthazar being one of the Magi who visited baby Jesus) are fully intentional. This soulful-eyed critter is, as stated by one of the human characters, a saint, whose purity and innocence contrast mightily with the unsaintly demeanor of the surrounding humans.

Those humans behave in the standard Bressonian manner. This means they all act oddly stilted and detached, gleaned by Bresson’s method of deliberately over-rehearsing the non-professional “models” (his word for actors) until they lost all trace of actory pretention, thus allowing him to manipulate them as he pleased.

In spite—or possibly because—of Bresson’s methods the late Anne Wiazemsky delivers an extremely moving turn as Balthazar’s primary owner Marie, a troubled young woman who can’t tear herself away from her punk boyfriend Gérard (François Lafarge). The latter is constantly in trouble, although Bresson doesn’t fill us in on the reasons for that, and nor is it ever made too clear why Marie is so insistent on staying with him.

The untrained donkey who plays the title role delivers the most emphatic performance, taking to Bresson’s minimalist style disarmingly well. I don’t think I need to inform you that the critter’s ultimate fate, set to a Schubert sonata, is a bleak one. That’s in keeping with animal films ranging from OLD YELLER to HACHI: A DOG’S TALE, which all seem to conclude with their non-human protagonists dying.

Yet dark endings were very much a Bresson mainstay, as proven by his follow up film MOUCHETTE (1967). It was adapted from a novel by the very Catholic-minded Georges Bernanos (father of Michel), who also provided the source material for DIARY OF A COUNTRY PRIEST/Journal d’un cure de campagne (1951), Bresson’s most famous film (although 1959’s PICKPOCKET has been steadily gaining in popularity). In Bresson’s hands the material becomes an donkey-less redo of AU HASARD BALTHAZAR, with the title character, a put-upon young girl (Nadine Nortier) so desperate for human connection she cozies up to two of the many scumbags who populate her village, existing as a combination of Balthazar and Marie. Her fate is even hairier than that of the donkey, although the “Transcendental Style” (as termed by Paul Schrader) is nearly identical to that of the former film, and indeed much of Bresson’s filmography: he only ever used a 50mm lens (the so-called “normal lens”), was quite sparing in his use of music, utilized ultra-spare black-and-white imagery (his first color film wasn’t until 1969) and relied heavily on close-ups (rather than dialogue or emoting) to advance the narrative and convey emotion.

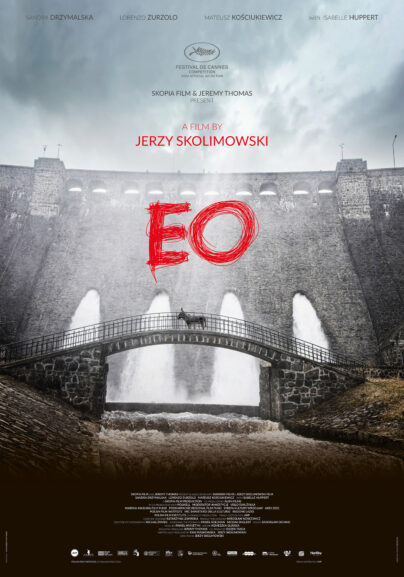

Poland’s Jerzy Skolimowski, who claims the only time he ever cried in a movie was while viewing AU HASARD BALTHAZAR, had no such ascetic tendencies. Skolimowski emerged from the Polish New Wave cinema movement of the 1950s and 60s, which turned out luminaries like Andrzej Wajda, Wojciech Has and Skolimowski’s longtime colleague Roman Polanski (with whom Skolimowski co-scripted 1962’s KNIFE IN THE WATER/Nóz w wodzie). Over the decades Skolimowski has followed his own highly mercurial muse through various countries, with his latest film EO (2022) returning this 84 year old auteur to his native land, and his avant-garde roots.

1960s releases like WALKOVER and RYSOPIS (both 1965) got the young Skolimowski dubbed one of the “world’s greatest directors” by Jean-Luc Godard. Unfortunately Skolimowski’s subsequent reputation has been affected by the fact that he’s been inextricably bound with the aforementioned Roman Polanski. Certainly the two men’s respective filmographies have been complimentary, as both favor contained psychodramas in which voyeurism and perversity take center stage, with Skolimowski’s DEEP END (1970) and MOONLIGHTING (1982) playing remarkably like Roman Polanski projects (and there are also real world parallels; on March 10, 1977, for instance, Polanski was arrested for sexually abusing 13-year-old Samantha Gailey in Jack Nicholson’s Hollywood pool house, just as Skolimowski was on his way to meet with Nicholson at the latter’s vacation home in Aspen).

EO is one Skolimowski project that won’t ever be confused with Polanski. Executive produced by Jeremy Thomas (who also did the honors on Skolimowski’s previous films THE SHOUT, ESSENTIAL KILLING and 11 MINUTES), it’s an original vision whose links to AU HASARD BALTHAZAR are undeniable. Once again we follow a donkey whose purity and innocence put it directly at odds with mankind, albeit in full color, and with a notably humanistic viewpoint, decreed by an end credits claim that “This film was made out of our love for animals and nature.” EO also has political concerns that set it apart from Bresson’s Catholic-infused viewpoint, with Skolimowski providing a deeply corrosive portrait of modern Europe.

Eo, named after the sound a donkey makes (in Polish at least), is first seen performing in a Polish carnival. He’s cared for by a young woman (Sandra Drzymalska) whose relationship with the animal might possibly go beyond the bounds of propriety. When financial issues shutter the carnival Eo embarks on an aimless odyssey through Europe, where he’s caged, abused, made witness to all manner of violence, and eventually meets a dark (but not unexpected) fate.

Skolimowski presents Eo’s journey in a visually rapturous and oft-impressionistic manner. This donkey is prone to visions and hallucinations, constantly flashing back to his time in the carnival and at one point imagining himself a robot. In this sense EO recalls Jean-Jacques Annaud’s THE BEAR/L’ours (1988), a film that, although little remembered today, was considered a breakthrough, with painstakingly achieved animal footage that was unprecedented in its drama and intimacy. As EO did with its donkey protagonist, THE BEAR followed a bear cub through various trials and tribulations, with occasional peeks inside the critter’s head to show its dreams.

What gives EO its distinction is, unlike THE BEAR but very much like AU HASARD BALTHAZAR, the immersive portrayal of its non-animal characters. Unfortunately it’s here that Skolimowski falters, with a dull bit in which Eo is taken in by an Isabelle Huppert led family of rich eccentrics being especially interminable. So long as Skolimowski foregrounds his inert but quite soulful non-human protagonist, played by a donkey named “Tako” and five doubles, the film registers as a unique, and uniquely touching, piece of work. But it doesn’t approach Bresson, he having gotten there first and done it best.