The following may well be the most contentious piece I ever write. The subject is the late, great Andrei Tarkovsky, and what I believe was his preference for the “lower” genres, including (yes) horror. I realize that to many of you this won’t mean much, but to others it will be equivalent to wiping boogers on a crucifix.

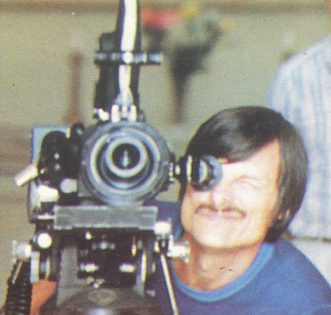

If you’re a film buff you more than likely know the work of Russia’s Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-1986). His films—THE STEAMROLLER AND THE VIOLIN, IVAN’S CHILDHOOD, ANDREI ROUBLEV, SOLARIS, MIRROR, STALKER, NOSTALGIA and THE SACRIFICE—are hermetic, arty and quite brilliant in their way. They’re also worshipped by movie mavens the world over.

Tarkovsky fans are among the most passionate and obsessive in existence. God help those who malign Tarkovsky’s films online or in print, or, worst of all, misbehave during screenings. During an L.A. revival of NOSTALGIA I witnessed a snickering man get punched in the face (by a woman!). Another example of obsessive Tarkovsky fandom is this internet post regarding the 2002 SOLARIS redo: “I hope everyone involved in this remake dies a slow, miserable death from a combination of every painful disease known to man.” Furthermore, when Ruscico put out STALKER on DVD with remixed stereo sound in place of the original mono track, fan outrage was so intense the company was forced to re-release the film with its proper soundtrack.

Tarkovsky fans are among the most passionate and obsessive in existence.

Tarkovsky fanaticism is a subject I know something about, as up until about a decade ago I myself was a massive Andrei Tarkovsky buff. Back in my college days I made sure to catch every Tarkovsky film screening I possibly could, read whatever was available on his work, and once chastised some friends for daring to sit out a retrospective of his films. Nor was I shy about broadcasting my knowledge of and passion for Tarkovsky’s cinema: a college term paper I wrote on the subject received an unheard-of 105 percent.

These days I still admire Tarkovsky’s work but am no longer as fanatical as I once was. It’s my contention that the Tarkovsky mentored Russian filmmakers Konstantin Lopushanksy (LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN), Alexander Sokurov (MOTHER AND SON) and Sergei Bodrov (MONGOL) have all surpassed their master in techniques he pioneered. There’s also the fact that my feelings regarding Tarkovsky and his attitudes have changed. Like most Tarkovsky fans, I once had an unwavering belief that he was far, far above such petty genres as horror or science fiction. One prominent critic, in an essay on Tarkovsky’s oeuvre, blithely dismissed his science fiction dramas SOLARIS (below) and STALKER as, simply, “lesser films.”

Years ago I’d have concurred, but now I beg to differ—in fact, I feel STALKER is very likely Tarkovsky’s finest work.

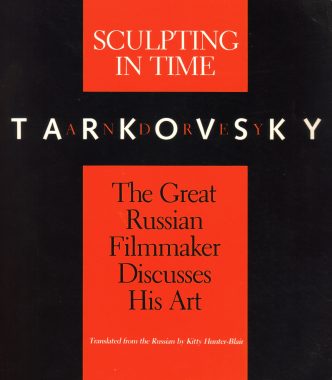

Tarkovsky elucidated his feelings about art and filmmaking in his 1986 book SCULPTING IN TIME, a stern, hectoring screed about, variously, the primacy of personal expression over commercial considerations, the importance of serious art/cinema over mere entertainment, and the complete banishment of anything fun from one’s movie making/viewing palette. Among the book’s conclusions (as translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair): “Cinema should be a means of exploring the most complex problems of our time, as vital as those which for centuries have been the subject of literature, music and painting”…“The true cinema image is built upon the destruction of genre, upon conflict with it”…“We now have a situation where audiences very often prefer commercial trash to Bergman’s WILD STRAWBERRIES or Antonioni’s ECLIPSE.”

Tarkovsky elucidated his feelings about art and filmmaking in his 1986 book SCULPTING IN TIME, a stern, hectoring screed about, variously, the primacy of personal expression over commercial considerations, the importance of serious art/cinema over mere entertainment, and the complete banishment of anything fun from one’s movie making/viewing palette. Among the book’s conclusions (as translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair): “Cinema should be a means of exploring the most complex problems of our time, as vital as those which for centuries have been the subject of literature, music and painting”…“The true cinema image is built upon the destruction of genre, upon conflict with it”…“We now have a situation where audiences very often prefer commercial trash to Bergman’s WILD STRAWBERRIES or Antonioni’s ECLIPSE.”

These days I still admire Tarkovsky’s work but am no longer as fanatical as I once was.

Imagine that! Imagine, also, someone choosing to view James Glickenhaus’s infamous DEATH WISH rip-off THE EXTERMINATOR (below) over Alain Resnais’ far more artistic MON ONCLE D’AMERIQUE, as the latter was apparently “too mechanical” (TARKOVKSY, p. xiv). Or dismissing the artistic cinema of Stan Brakhage because it “hurts the eyes” (as recalled by J. Hoberman in VULGAR MODERNISM) and the films of Hungary’s Miklos Jancso as “Monstrous rubbish” (TIME WITHIN TIME, p. 235). Or branding Bernardo Bertolucci’s LUNA as “Monstrous, cheap, vulgar rubbish” and Luis Bunuel’s TRISTANA a “very bad film” (TIME WITHIN TIME, ps. 22, 205).

Who would say such things? Try Mr. Andrei Tarkovsky, to whom the above quotes directly refer.

Who would say such things? Try Mr. Andrei Tarkovsky, to whom the above quotes directly refer.

Further evidence abounds that Tarkovsky wasn’t quite as pedantic about “artistic” cinema as he let on. In SCULPTING IN TIME he names his closest cinematic peer as the aforementioned Luis Bunuel, who in addition to the “very bad” TRISTANA is most famous for the outrageous surreal shock fests UN CHIEN ANDALOU and L’AGE D’OR. Tarkovsky’s posthumously published diaries (collected in the volume TIME WITHIN TIME) reveal that among the films he chose to see were Andrzej Zulawski’s crazed exploitation freak-out POSSESSION, Lucio Fulci’s notorious trash-fest ZOMBI 2 and Peter Weir’s horrific THE LAST WAVE. Also, in a 1997 Sight and Sound article Tarkovsky colleague Layla Alexander Garrett reveals that he “could talk for hours” about THE TERMINATOR.

Tarkovsky supporters have been careful to make excuses for their hero’s excursions into pulp: in her 1989 book TARKOVSKY, Maya Turovskaya claimed that Tarkovsky only viewed such fare because he was trying to keep up with popular trends. Also, in nearly every case Tarkovsky was careful to denounce those errant films for their lack of artistry, not unlike a smack addict who warns his friends against taking drugs.

Tarkovsky supporters have been careful to make excuses for their hero’s excursions into pulp: in her 1989 book TARKOVSKY, Maya Turovskaya claimed that Tarkovsky only viewed such fare because he was trying to keep up with popular trends. Also, in nearly every case Tarkovsky was careful to denounce those errant films for their lack of artistry, not unlike a smack addict who warns his friends against taking drugs.

After admitting to seeing THE EXTERMINATOR, for instance, Tarkovsky counseled an interviewer that “there can be no talk of art in relation to films like THE EXTERMINATOR” (really?), just as he privately railed against the “unspeakably revolting” POSSESSION and dismissed ZOMBIE 2 as “repulsive trash.” Why then did he continue to see such films? Did he really expect artistic refinement from movies entitled THE EXTERMINATOR or ZOMBIE 2?

See Also: SHADOWS OF FORGOTTEN ANCESTORS

It’s my contention that Tarkovsky knew exactly what he was getting into when he purchased tickets to those films, and possibly even enjoyed the experience. Mind you, I’m not suggesting he was in any way insincere in his anti-populist stance, just that, like most of us, he held diametrically opposed yet equally sincere ideals he was loath to admit to. He may not have been a horrormeister, but it’s my belief that Tarkovsky had a liking for the lower genres, and demonstrated it in his films.

Regarding those films, they’re slow, enigmatic and oriented around expansive visual design; in short, very nearly the epitome of what we’ve come to think of as Art Films. Yet they contain such genre staples as ghosts (MIRROR and NOSTALGIA), witchcraft (ANDREI ROUBLEV and THE SACRIFICE), zombies (SOLARIS), alien invasion (STALKER), space travel (SOLARIS again) and nuclear Armageddon (THE SACRIFICE).

You can argue that Tarkovsky was simply using those elements as a means to an end in the manner of fellow art film maestro Ingmar Bergman, who often utilized genre elements. The difference between the two is that Tarkovsky lived and worked in an extremely repressive regime that vigorously stressed the tenants of “Soviet Naturalism” above all else. Science fiction was tolerated in this climate but the supernatural not at all; it’s no accident that the number of Soviet horror movies made during the sixties and seventies, Tarkovsky’s most fertile period, can be counted on one hand.

Thus Tarkovsky’s artistic predilictions were downright subversive in communist Russia. His ideals got him in no small amount of trouble with communist authorities, and resulted in his leaving the country in 1980. This means Tarkovsky’s incorporation of genre elements in such a repressive environment could only have emerged from a deep-seated conviction, and were not a mere means to an end.

Of course the other extreme of Tarkovsky’s attitudes (as exemplified by SCULPTING IN TIME) is also on display in his films, particularly SOLARIS and STALKER, the most overtly genre-centered of them all. Both conclude with their respective protagonists engaging in lengthy philosophical reveries that offset the fantastic and horrific elements. Here we get a glimpse of the Tarkovsky who chose to see THE EXTERMINATOR and POSSESSION only to vigorously denounce them afterward, as concluding SOLARIS and STALKER with heavy-handed chatter in place of proper endings seems an extension of that same impulse. Tarkovsky evidently didn’t feel the need to do that in ANDREI ROUBLEV, MIRROR or NOSTALGIA!

Of course the other extreme of Tarkovsky’s attitudes (as exemplified by SCULPTING IN TIME) is also on display in his films, particularly SOLARIS and STALKER…

Yet interestingly enough, projects Tarkovsky had in the works (but never got around to actually making) include adaptations of FAUST, Carlos Castaneda’s mystical text THE TEACHINGS OF DON JUAN and Mikhail Bulgakov’s fantastic satire THE MASTER AND MARGARITA. An even more intriguing possibility was breached by actress Natalaya Bonderchuck (the space babe of SOLARIS), who in an interview on the Criterion SOLARIS DVD hinted that Tarkovsky tried to find work in Hollywood in the late seventies. This would appear to be confirmed by filmmaker Ken Russell, who in his 1991 autobiography reveals that Tarkovsky was once under consideration to direct ALTERED STATES (1980).

Tarkovsky working in Hollywood? That seems a pretty outrageous idea, though maybe not entirely out of the realm of possibility. Tarkovsky’s onetime colleague Andrei Konchalovsy (co-writer of THE STREAMROLLER AND THE VIOLIN and ANDREI ROUBLEV) relocated to the U.S. in the 1980s, and even thrived for a time, helming RUNAWAY TRAIN, SHY PEOPLE, TANGO AND CASH and the miniseries version of THE ODYSSEY.

An Andrei Tarkovsky directed film of ALTERED STATES doesn’t seem that farfetched given his evident interest in  horror and science fiction. As for the action cinema so integral to Hollywood, I find it a little harder to picture how Tarkovsky might have fared, although Konchalovsky’s example gives some indication—I believe the mystically-tinged final scenes of RUNAWAY TRAIN (1985) provide a tantalizing suggestion of how a Tarkovsky directed action movie might have played.

horror and science fiction. As for the action cinema so integral to Hollywood, I find it a little harder to picture how Tarkovsky might have fared, although Konchalovsky’s example gives some indication—I believe the mystically-tinged final scenes of RUNAWAY TRAIN (1985) provide a tantalizing suggestion of how a Tarkovsky directed action movie might have played.

My conclusion? That had Andrei Tarkovsky’s fortunes been different, his career may well have taken a decidedly less artistic direction. Lars von Trier’s 2009 sex-and-gore opus ANTICHRIST concludes with a dedication to Tarkovsky; that seemed a perverse gesture to many, but it may actually be more appropriate than we know.