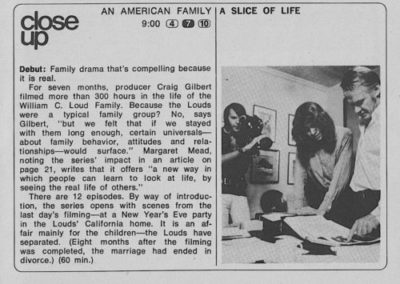

AN AMERICAN FAMILY, a 12 episode docu-series that aired on PBS in 1973, is very likely the most famous yet least seen TV program in history. Often called the first-ever reality TV show, it was accompanied by a publicity blitz that included a plethora of TV interviews, magazine spreads and a paperback tie-in by the science fiction novelist Ron Goulart, and was rerun numerous times during the eighties and early nineties. Since then, alas, the program has been tied up in licensing woes surrounding the Beatles and Rolling Stones tunes that are played throughout, and so has largely dropped out of sight (outside a two hour compilation DVD released in 2011, which I say is worthless, as one really needs to experience the full twelve hours for a full appreciation).

AN AMERICAN FAMILY, a 12 episode docu-series that aired on PBS in 1973, is very likely the most famous yet least seen TV program in history. Often called the first-ever reality TV show, it was accompanied by a publicity blitz that included a plethora of TV interviews, magazine spreads and a paperback tie-in by the science fiction novelist Ron Goulart, and was rerun numerous times during the eighties and early nineties. Since then, alas, the program has been tied up in licensing woes surrounding the Beatles and Rolling Stones tunes that are played throughout, and so has largely dropped out of sight (outside a two hour compilation DVD released in 2011, which I say is worthless, as one really needs to experience the full twelve hours for a full appreciation).

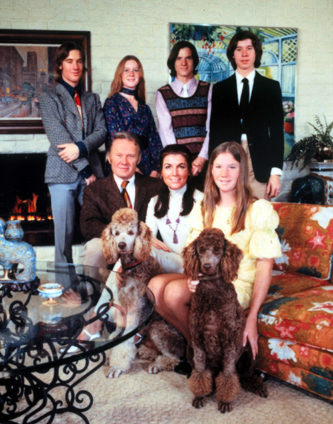

Produced by Craig Gilbert and visualized by Alan and Susan Raymond, AN AMERICAN FAMILY was filmed from May through December of 1971. Its subject was the Louds, a family residing in a scenic Santa Barbara, CA house. As Gilbert makes clear in an on-camera spiel delivered in the premiere episode, the Louds were not representative of the American family, being, rather, “an American family”—and an extremely affluent one whose existence appears impossibly placid given the unsettled era in which they were living. The Vietnam War, the draft and the mid-1971 publication of the Pentagon Papers are all left undiscussed, with the biggest outside issue facing the family being a workers’ strike that could conceivably threaten the Louds’ financial well-being.

Of this motley crew only the family patriarch, one Bill Loud, evidences any real initiative. Difficult though it might seem to believe nowadays, the Louds were able to maintain their affluent existence on a single income: Bill’s, gleaned from his employment as a mining company CEO. The overriding (and possibly unintentional) theme here would appear to be the corrosiveness of affluence.

Bill’s wife Pat, an attractive woman burdened with a retinue of hideous outfits, spends her days lounging around their house whining about the laziness of her five children. Bill, an old school republican, also bitches about his kids’ lack of motivation, although he’s not much of role model; a scene in which he and Pat attempt to cajole their seventeen year old son Grant into getting a summer job is hilarious, given that both parents are lounging around the  family swimming pool as they pontificate about the importance of hard work (a fact that clearly isn’t lost on Grant).

family swimming pool as they pontificate about the importance of hard work (a fact that clearly isn’t lost on Grant).

Another of the Loud children is the overtly gay twenty year old Lance, who as the series opens has decamped to NYC to write for an underground newspaper. The sole breakout star to emerge from AN AMERICAN FAMILY, Lance is widely alleged to have come out onscreen, although that claim (as he himself subsequently admitted) is false, as he was in fact out long before filming commenced. Pat and Bill would appear to be accepting of Lance’s sexuality, although one can’t help but read a bit more into Bill’s complaint about Lance being “the greatest con artist you ever saw” than is actually stated. As it happens, Lance is indeed something of a con artist, subsiding in NYC entirely on handouts from friends and family, and then travelling to Paris, where he runs out of money and eventually heads home, with his flamboyant presence dominating the final two episodes.

Of Lance’s siblings the aforementioned Grant, an aspiring rock ‘n’ roller, is given the most screen time. An all-around lazy fuck, he’s seen watching copious amounts of television, loafing his way through a cementing job and trashing his parents’ Volvo. There’s also the fourteen year old aspiring dancer Michelle, eighteen year old Kevin, whose primary import to the series occurs via a highly dramatic departure for Hawaii in episode seven, and sixteen year old Delilah, who likewise has little to do (outside of providing a troubled expression that makes for an unforgettable concluding freeze frame to episode seven).

What drives the series is Bill and Pat’s rocky marriage, which, as we’re informed in the opening moments of the first episode, is nearing its end. From there the series utilizes fractured chronology to track the dissolution of this thirty one year coupling. Tension is evident in scenes like the one in which Pat is ignored by Bill as he holds court at a dinner gathering, and in her anguished reactions to the news of his many “business trips.” It takes until episode six for Pat to formally file for divorce—she’s admittedly suffering from empty nest syndrome, as her children are leaving home and she finds the many resentments that have accrued over the years boiling over—although Bill’s reaction isn’t made evident until episode nine, with the filmmakers spending episodes seven and eight flashing back.

The nonlinear time frame ensures that many dramatic elements, such as a brush fire that nearly decimates the Loud home and a subsequent kitchen confrontation between Pat and Bill, are discussed early on i n the series but not actually shown until subsequent episodes. I’m not sure that this helps or hinders things appreciably, but it is one of the program’s most striking, and least remarked upon, stylistic features.

n the series but not actually shown until subsequent episodes. I’m not sure that this helps or hinders things appreciably, but it is one of the program’s most striking, and least remarked upon, stylistic features.

Also noteworthy is the stateliness of the filmmaking. Surprisingly for a series that was widely derided in its day as the epitome of trash TV, AN AMERICAN FAMILY is much closer in tone and feel to the seminal documentaries of Frederick Wiseman and Allan King than THE REAL WORLD or BIG BROTHER, being contemplative and even artful in its approach.

In the manner of the aforementioned Wiseman and King docos, the particulars of AN AMERICAN FAMILY are mostly left to speak for themselves, with narration delivered in short, terse and largely superfluous bursts (“It is a time of departures from 35 Wooddale Lane”). The filmmakers’ primary goal, it would seem, was simply to spend time with these characters, resulting in a lot of lengthy stretches in which the principals walk, drive or sit around doing nothing. The effect is quite off-putting initially, yet the series grows increasingly engrossing as it advances, with the viewer adjusting to the ultra-slow pacing as s/he gets to know these characters and emotionally invest in their various dilemmas.

One especiallyaffecting portion occurs in episode two, consisting of Pat’s visit to Lance in NYC’s fabled Chelsea Hotel. By the end of the episode the two are barely speaking, with their fundamental estrangement (possibly engendered by homophobia) laid uncomfortably bare. A similar effect is achieved in episode six when Grant picks up his father, who’s been out of town (another “business trip”), at the airport after Pat has filed for divorce; the camera focuses in on Grant’s nervously twisting hands as he chats with his father (the first, it turns out, of several wringing hand close-ups). Another noteworthy episode six moment involves a nifty shock cut from Grant listening to a Rolling Stones tune on his car radio to a plane landing, adding an appropriate note of foreboding to the portentous revelations to come.

Of course the level of “reality” here, like those of AN AMERICAN FAMILY’S reality TV offshoots, is constantly in  question. Note how oftentimes when the Louds speak on the phone the voices on the other end are fully audible on the soundtrack, and a lengthy passage allegedly depicting the Loud children as infants, which looks a bit too burnished to be fully believable as 1950s-era home movie footage (as an end credits title makes clear, the film utilized in this section was super 8mm, which didn’t exist before 1965).

question. Note how oftentimes when the Louds speak on the phone the voices on the other end are fully audible on the soundtrack, and a lengthy passage allegedly depicting the Loud children as infants, which looks a bit too burnished to be fully believable as 1950s-era home movie footage (as an end credits title makes clear, the film utilized in this section was super 8mm, which didn’t exist before 1965).

Further questions about the veracity of what we’re seeing occur in episode nine, when Pat informs Bill that she’s filed for divorce; his oddly nonchalant reaction is indicative of the widely made allegation that the marriage was in trouble long before filming began (something Bill all-but admits in a subsequent voice-over). I’ll also question the extended plug for SESAME STREET, PBS’s other major series, that occurs during a high school talent show in episode three.

Beyond that the series stands as, simply, a first-rate depiction of life in 1971—indeed, this may well be the definitive early seventies TV time capsule. Note the clothing, hairstyles and annoying granny glasses worn by seemingly all the adults, and the fact that there’s nary a computer monitor or cell phone in sight. The none-too-enlightened attitudes of the time are also laid bare, as in a bit in which the just-divorced Pat attempts to find solace with a friend, who reacts first by questioning why Pat waited twenty years to file, and then by bluntly informing her that she probably wasn’t doing enough to keep her hubbie from straying. Even the filmmaking is redolent of the era, with its sudden zooms in and out on people’s faces (which more often than not necessitate an equally jarring focus adjustment) and raggedy sound recording in which the background ambience often obscures, if not drowns out entirely, the main dialogue. Clearly, the inception of digital sound was still far in the future.

That the program was quite influential goes without saying. One need only look to our current reality TV infected media landscape to confirm that, and also the many films directly inspired by AN AMERICAN FAMILY (such as 1979’s REAL LIFE and 1994’s LOUIS THE 19th, KING OF THE AIRWAVES, which was remade as ED TV in ‘99). As to the series’ ultimate effect on its participants, it took another ten years for that information to be made public.

The hour-long mini-doco AN AMERICAN FAMILY REVISITED: THE LOUDS 10 YEARS LATER aired on HBO in 1983. Made by Alan and Susan Raymond, it contained retrospective interviews with all the Louds, who, amazingly enough, appeared to have done quite well for themselves. Bill, we learn, moved on from the divorce and got remarried while Pat claimed to have found contentment after relocating to New York City. The kids even found jobs and Lance toned down his flamboyant mannerisms.

About AN AMERICAN FAMILY the Louds are mostly positive, claiming it was great fun to film (and so rubbishing the popular claim that the filming was responsible for the break-up of Bill and Pat’s marriage). The problems, it seems, stemmed from the media intrusions that followed in the wake of the series’ enormous success, although Pat and Lance admittedly used that attention to their advantage.

About AN AMERICAN FAMILY the Louds are mostly positive, claiming it was great fun to film (and so rubbishing the popular claim that the filming was responsible for the break-up of Bill and Pat’s marriage). The problems, it seems, stemmed from the media intrusions that followed in the wake of the series’ enormous success, although Pat and Lance admittedly used that attention to their advantage.

Things came full circle in 2003, in LANCE LOUD!: A DEATH IN AN AMERICAN FAMILY. It was another hour long doco, broadcast this time on PBS. Its focus was Lance Loud, who died of aids in December 2001. Featured are extensive archival interviews with Lance and more recent ones with Pat and Bill, who both tear up when recalling their son’s life. Lance, it’s revealed, became an extremely prolific journalist in the years since AN AMERICAN FMAILY REVISITED, and also an intravenous drug user, which apparently contributed to his demise. His dying wish was for his parents to get back together and, according to a postscript, Pat and Bill did in fact commence living together after Lance’s death.

In the years since the Louds have largely kept quiet, with Bill passing away in 2018. This has occurred just as popular culture, ironically enough, has gained a newfound interest in AN AMERICAN FAMILY. An HBO movie about the making of the series, CINEMA VERITE, was broadcast in 2011, with Diane Lane as Pat Loud, Tim Robbins as Bill, Thomas Dekker as Lance and James Gandolfini as the show’s creator Craig Gilbert—who’s portrayed as a scheming manipulator who nearly destroys the family and himself in his quest for “truth.” The film isn’t bad, doing a credible job of recreating the look and feel of AN AMERICAN FAMILY while showing the behind-the-scenes drama with nearly-as-convincing results. If it ultimately left me somewhat cold it’s probably because, accomplished though CINEMA VERITE is, it simply can’t hope to match the intrigue, outrage and sheer unholy fascination of the program that inspired it.