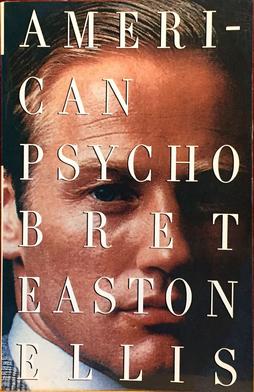

If you were a reader back in 1991, as I was, then you probably recall, as I do, the furor that accompanied the publication of AMERICAN PSYCHO. It was bounced by its original publisher Simon & Schuster after outraged feminist groups leaked many of the book’s most gruesome passages, despite the prestige of its author Bret Easton Ellis, who became a literary darling after publishing the eighties mainstay LESS THAN ZERO.

If you were a reader back in 1991, as I was, then you probably recall, as I do, the furor that accompanied the publication of AMERICAN PSYCHO. It was bounced by its original publisher Simon & Schuster after outraged feminist groups leaked many of the book’s most gruesome passages, despite the prestige of its author Bret Easton Ellis, who became a literary darling after publishing the eighties mainstay LESS THAN ZERO.

AMERICAN PSYCHO, Ellis’s third novel, ended up debuting as a Vintage trade paperback, to an astonishing amount of controversy. The only comparable recent example I can think of, in the publishing world at least, was the appearance of THE SATANIC VERSES a couple years earlier, which incited a veritable media storm after the life of its author Salman Rushdie was threatened by Muslim extremists. Of course, in that instance critics rushed to Rushdie’s defense, while the reaction to AMERICAN PSYCHO was diametrically opposite (as exemplified by a venomous review entitled “Snuff This Book!”). It also inspired a number of withering critiques from many established horror writers, who, in the words of author Poppy Z. Brite, viewed Ellis’ foray into the genre as “upstart yuppie scum invading ‘their’ territory”. The genre scribes Ramsey Campbell and James M. Kisner both savaged AMERICAN PSYCHO in print (predictably, much of their criticism centered around Ellis’s $300,000 advance, with Kisner pointedly asking “does that mean you have to pander to mankind’s bases feelings to make any real money in this business?”) and Stephen King publicly derided it by dubbing Rex Miller’s SLOB “twice the book”.

AMERICAN PSYCHO, Ellis’s third novel, ended up debuting as a Vintage trade paperback, to an astonishing amount of controversy.

Fifteen years later the furor has obviously died down. Recent editions of AMERICAN PSYCHO contain critical blurbs from the likes of Gore Vidal and Katherine Dunn (whereas back in ’91 it was difficult to find anyone willing to say anything even remotely positive about it) and a watered-down film version was released in 2000 to critical raves. Even the horror community appears to have made peace with it, judging by the book’s inclusion in the 2005 anthology HORROR: ANOTHER 100 BEST BOOKS.

The irony is that AMERICAN PSYCHO remains every bit as relevant and shocking now, if not more so, than it was back in 1991. I read it when it first hit the scene, as a teenager, and as I recall my reaction was much the same upon rereading it as a grown up. Despite the plethora of “topical” references—to things like Spuds Mackenzie, LES MISERABLES, Huey Lewis and the News, VHS videos and Evian water—Ellis’s central targets are racism, hypocrisy, violence and rampant materialism, all of which are still very much with us. Perhaps this is why the book remains readily available today, even as Ellis’s five or six other novels have largely vanished from the public eye, if not from print altogether. Quite simply, AMERICAN PSYCHO refuses to die.

The irony is that AMERICAN PSYCHO remains every bit as relevant and shocking now, if not more so, than it was back in 1991.

AMERICAN PSYCHO, for those who don’t know, is the first person account of Patrick Bateman, a twenty-six-year-old yuppie living in Manhattan during the latter 1980s, a world Ellis, being a longtime NYC resident, clearly knows inside and out. Employment-wise Bateman, in his creator’s own words, makes “enormous amounts of money for doing basically nothing.” As a narrator Bateman is a bit—okay, very—exasperating; he tends to drone on and on about his grooming habits, choice of attire, favored restaurants and what his equally materialistic companions are wearing. He’s quite fastidious in the latter aspect: nearly every character in the book is introduced via an exhaustive appraisal of who designed their every item of clothing and footwear, followed by equally exhaustive descriptions of the boring conversations they have, making for long stretches of, essentially, nothing.

Such, however, is the author’s intention—this is, as Ellis has admitted, “a very annoying book.” That tendency carries over into minutely described passages of sex and mutilation, in which Bateman, in much the same way he describes his daytime lifestyle, regales his penchant for cold-blooded murder. His favored victims are bums (usually of the African-American persuasion, or, Bateman’s preferred term, niggers) and women he’s just screwed (or had bang other women while he watched), whom he dispatches via knife, nail gun, chainsaw and a rat that, in the book’s most notorious passage, Bateman releases into a woman’s vagina. Even though they don’t occur until over a hundred pages in, the nasty bits are some of the most intense I’ve encountered in any book, rivaling those of down-and-dirty authors like Sean Hutson and Edward Lee. That’s in addition to numerous sex scenes that wouldn’t feel out of place in the most fervid pornography.

Ellis’s central targets are racism, hypocrisy, violence and rampant materialism, all of which are still very much with us.

In spite of such excesses, though (or perhaps because of them), Ellis never loses his satiric edge. After many of the more graphic passages Bateman offers pithy essays on his favorite pop artists, which if you read closely offer a number of revealing insights into the character’s psyche—particularly telling is his dissertation on Huey Lewis and News, in which Bateman touts “the pleasures of conformity and the importance of trends.”

The joke, of course, is that Bateman, being the emotionless serial killer he is, fits in perfectly with America’s elite, whose ingrained racism and shallowness are traits shared by most mass murderers. The book’s critics have argued, not without some justification, that Ellis belabors the point with his insanely drawn-out descriptions and bloated 399 page length. Again, though, it was the author’s stated intention to rub our noses in Bateman’s excesses.

The film version by director Mary Harron (replacing David Cronenberg and Oliver Stone, both at various times slated to direct) is overtly satirical and one-dimensional, toning down the sex and violence considerably. This was apparently enough for squeamish critics, who were far nicer to the movie than they were the book. In my view, however, Harron’s approach tarnishes the power of the book, which is in fact a far more insightful, multi-faceted work than it’s generally given credit for. I myself, having read AMERICAN PSYCHO twice, find it alternately obnoxious, repellant, boring, offensive…and undeniably fascinating. In spite of its annoyances, it’s a curiously compelling tome whose insights haven’t dimmed with age.

Patrick Bateman may be a creature of the eighties, but he definitely sounds like he’d thrive in our present-day landscape—indeed, based on the above quote, he’d probably be elected president.

Consider: in modern America the divide between the haves and have-nots has widened substantially, while nearly every decision our current president makes seems designed to benefit the fortunes of the top five percent. Patrick Bateman would definitely be proud. He’d also be pleased, I’m sure, to see that Donald Trump, who’s referenced throughout AMERICAN PSYCHO, not only remains in the news but is now a network TV star.

In one particularly revealing passage of AMERICAN PSYCHO, Bateman, in an introspective mood, observes that “there wasn’t a clear, identifiable emotion within me, except for greed and, possibly, total disgust. I had all the characteristics of a human being—flesh, blood, skin, hair—but my depersonalization was so intense, had gone so deep, that the normal ability to feel compassion had been eradicated, the victim of a slow, purposeful erasure.” Patrick Bateman may be a creature of the eighties, but he definitely sounds like he’d thrive in our present-day landscape—indeed, based on the above quote, he’d probably be elected president.

See Also: American Psycho, the Film