The early nineties saw a veritable explosion of films directed and headlined by minorities. African Americans directors led the charge with MO’ BETTER BLUES, TO SLEEP WITH ANGER, HOUSE PARTY, STRAIGHT OUT OF BROOKLYN, A RAGE IN HARLEM, UP AGAINST THE WALL, NEW JACK CITY, DAUGHTERS OF THE DUST, HANGIN’ WITH THE HOMEBOYS, BOYZ IN THE HOOD, JUNGLE FEVER, JUICE, BEBE’S KIDS, POSSE, JUST ANOTHER GIRL ON THE I.R.T., CLASS ACT, BOOMERANG, MALCOLM X, POETIC JUSTICE, DEEP COVER, MENACE II SOCIETY, THE FIVE HEARTBEATS, CROOKLYN, ONE FALSE MOVE, CB4, FEAR OF A BLACK HAT, THE INKWELL and I LIKE IT LIKE THAT, in addition to white people-directed “black” films like SOUTH CENTRAL, MO’ MONEY, WHO’S THE MAN? and FRESH. Of course by the end of the decade that deluge had become a trickle, but the achievement remains.

Latino filmmaking of the same era may not have been as prominent, but it was present—in a fashion. Hollywood had already undergone a mini-Hispanic boom in late 1980s, with films like LA BAMBA, BORN IN EAST LA and STAND AND DELIVER, and the ascendance of performers like Edward James Olmos, Sonia Braga and Maria Conchita Alonso. The early 1990s brought THE MAMBO KINGS and MI VIDA LOCA, Latino-headlined movies made by blanquitos, as well as THE HOUSE OF THE SPIRITS and THE PEREZ FAMILY, which despite being populated by Hispanics featured very few before or behind the camera.

Latino filmmaking of the same era may not have been as prominent, but it was present—in a fashion. Hollywood had already undergone a mini-Hispanic boom in late 1980s, with films like LA BAMBA, BORN IN EAST LA and STAND AND DELIVER, and the ascendance of performers like Edward James Olmos, Sonia Braga and Maria Conchita Alonso. The early 1990s brought THE MAMBO KINGS and MI VIDA LOCA, Latino-headlined movies made by blanquitos, as well as THE HOUSE OF THE SPIRITS and THE PEREZ FAMILY, which despite being populated by Hispanics featured very few before or behind the camera.

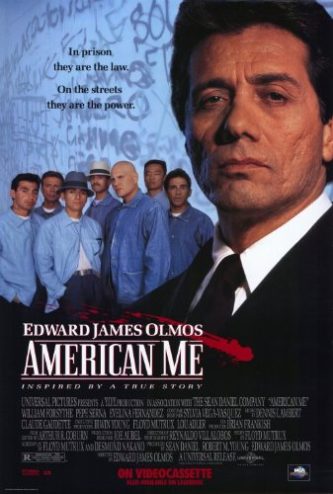

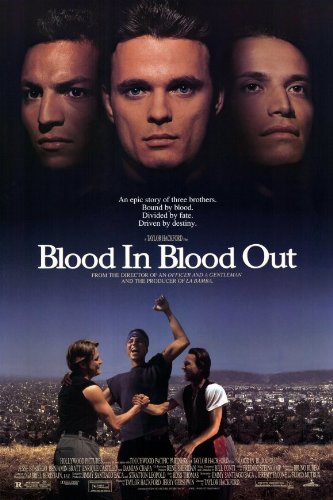

Then there was AMERICAN ME, a 1992 Universal release, and the following year’s BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT, from Disney’s Hollywood Pictures division. The two films are quite similar in conception, and were lensed virtually simultaneously. They share a direct connection in the form of actor Danny Trejo, who was sought for both. He only appeared, however, in BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT, shunning AMERICAN ME for its departure from the facts.

American Me

The facts are these: AMERICAN ME was based on the life of Rodolfo Cadena (1943- 1972), one of the founders of the notorious Mexican prison gang La eMe. The director/star Edward James Olmos plays him onscreen, alongside William Forsythe in a role closely patterned on Cadena’s mentor Joe Morgan (1929-1993). The latter and his fellow La eMe cohorts were upset by the film, most notably its depiction of the Cadena stand-in, here named Montoya Santana, getting raped as a child. According to Trejo, “no person who’d ever been violated in that way could ever rise to the top of a prison gang. They could be killers and bad motherfuckers, but they’d never run a gang. It wouldn’t happen. More importantly, it didn’t happen.”

1972), one of the founders of the notorious Mexican prison gang La eMe. The director/star Edward James Olmos plays him onscreen, alongside William Forsythe in a role closely patterned on Cadena’s mentor Joe Morgan (1929-1993). The latter and his fellow La eMe cohorts were upset by the film, most notably its depiction of the Cadena stand-in, here named Montoya Santana, getting raped as a child. According to Trejo, “no person who’d ever been violated in that way could ever rise to the top of a prison gang. They could be killers and bad motherfuckers, but they’d never run a gang. It wouldn’t happen. More importantly, it didn’t happen.”

Trejo further likens Olmos to “a kid playing with a grenade, thinking the whole time it was a sparkler.” His film, well intentioned though it was, resulted in the killings of three of AMERICAN ME’s technical advisors and, apparently, several more that occurred behind bars.

Yet AMERICAN ME, whatever its deviations from reality, is damn good. Olmos delivers one of his finest-ever performances as the near-insanely stoic Montoya Santana, a small time East LA thief who rises to power while incarcerated. The prison scenes, filmed on location in Folsom, are among the most brutal and realistic I’ve seen in any movie, providing an up close and uncomfortably personal look at underworld economics and their life-and-death implications.

Yet AMERICAN ME, whatever its deviations from reality, is damn good. Olmos delivers one of his finest-ever performances as the near-insanely stoic Montoya Santana, a small time East LA thief who rises to power while incarcerated. The prison scenes, filmed on location in Folsom, are among the most brutal and realistic I’ve seen in any movie, providing an up close and uncomfortably personal look at underworld economics and their life-and-death implications.

It’s that sense of unblinking reality that elevates AMERICAN ME above most other nineties gangster movies, and also the complete absence of any sort of romanticism (something that can’t be said for GOODFELLAS or KING OF NEW YORK). It does admittedly get a bit preachy in the final half hour, in which Santana starts to question his criminal proclivities after a lecture by his girlfriend (Evalina Fernandez), leading to him being killed by his own followers (another departure from the facts) and a coda that’s as relentless as can be imagined.

Olmos goes out of his way not to glamorize the mayhem, but that doesn’t appear to have entirely registered with his intended audience. I vividly recall a Chicano coworker back in ‘92 raving about AMERICAN ME, a “dope” movie with gangsters and violence (the fact that the film actually decried those things appeared to sail clear over his head), and it reportedly elevated public awareness of La eMe appreciably, serving as an unofficial recruitment PSA for the gang.

The film, for all that, wasn’t much of a success. Universal could conceivably have used the underworld activity surrounding the release to enhance its profile, but didn’t, resulting in what seemed to most prospective viewers like good-for-you Oscar bait. Its box office haul: an unimpressive $13,086,430 against a $15,000,000 budget.

Blood In Blood Out

Onto BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT, which Joe Morgan reportedly dubbed “The cute one.” In contrast to the former film, this one is jazzy, melodramatic and free of preachiness. The director was Taylor Hackford, who appears to have encouraged his performers to emote as histrionically as possible. Subtlety is nowhere to be found, with Hackford never missing a chance to heighten the melodrama. Such an approach is in keeping with Hispanic culture, which tends to favor grand emotions and overheated drama; Hackford may be a Hollywood-minded gringo (with a filmography that includes AN OFFICER AND A GENTLEMAN, DOLORES CLAIBORNE and THE DEVIL’S ADVOCATE), but he’s turned out an epic film that feels very Hispanic.

Inspired by the life story of poet Jimmy Santiago Baca, who co-wrote the screenplay, it centers on three Latino friends living in East L.A. (Jesse Borrego, Benjamin Bratt and Damien Chapa) whose lives take very different paths after a tangle with police. One of them (Chapa) goes to prison, another (Bratt) becomes a cop, and the third (Borrego) manages to elude the law and become an acclaimed artist. Over the course of a three hour plus stretch Chapa becomes a big shot in prison while Bratt zeroes in on his former amigos, and in so doing finds himself in a moral quandary.

The film is fast moving and entertaining despite its inflated running time. As with AMERICAN ME, the prison scenes, filmed on location in San Quentin, constitute the film’s most powerful moments (with Mr. Trejo appearing as one of the inmates); I wouldn’t call those scenes authentic (authenticity isn’t a term I’d associate with this film), but they have a queasy brutality that feels appropriate to the setting. The final half hour, alas, gets a bit messy from a storytelling standpoint, and the subdued L.A. reservoir set ending isn’t entirely satisfying. Overall, though, the film is a success, and more satisfying, in my view, than Edward James Olmos’s skilled but self-important predecessor.

The film is fast moving and entertaining despite its inflated running time. As with AMERICAN ME, the prison scenes, filmed on location in San Quentin, constitute the film’s most powerful moments (with Mr. Trejo appearing as one of the inmates); I wouldn’t call those scenes authentic (authenticity isn’t a term I’d associate with this film), but they have a queasy brutality that feels appropriate to the setting. The final half hour, alas, gets a bit messy from a storytelling standpoint, and the subdued L.A. reservoir set ending isn’t entirely satisfying. Overall, though, the film is a success, and more satisfying, in my view, than Edward James Olmos’s skilled but self-important predecessor.

BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT didn’t receive any of the underworld attention that greeted AMERICAN ME (with the fictional gang portrayed in BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT called “La Onda”), but its release was not without controversy. Disney, influenced by the disappointing showing of AMERICAN ME and the LA riots of spring 1992, shelved the film for over a year, and changed the title to the more generic BOUND BY HONOR. Its gross was even worse than that of AMERICAN ME: $4,496,583 against a $35,000,000 budget.

$35,000,000 budget.

Over the years, however, the film’s profile rose. Hackford convinced Disney to release it on VHS as BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT–BOUND BY HONOR, and it attracted a cult following that came to dwarf that of AMERICAN ME. Yet in April 2021 the latter film, upon its debut on Netflix, pulled back ahead, quickly claiming the #2 spot on that service. Of course, BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT is not streaming on Netflix, nor Amazon Prime, with its sole availability right now being the VHS and DVD releases (the latter a Director’s Cut that restores ten minutes shorn from the BOUND BY HONOR version). This means the battle isn’t over by any means, and if and when BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT does finally appear on streaming services I fully expect it to take its rightful place at the top of the list.