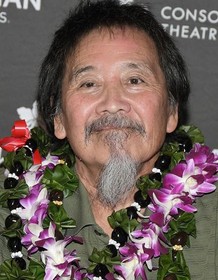

This week we bid farewell to one of America’s most unique filmmakers. There was simply no one else like the Hawaiian-bred Albert Pyun, one of the most irrepressible directors working in any genre. He wasn’t particularly well respected, and his final days were sad ones (with a hospitalized Pyun begging his fans for validation), but he left a sizeable mark on the American film scene.

This week we bid farewell to one of America’s most unique filmmakers. There was simply no one else like the Hawaiian-bred Albert Pyun, one of the most irrepressible directors working in any genre. He wasn’t particularly well respected, and his final days were sad ones (with a hospitalized Pyun begging his fans for validation), but he left a sizeable mark on the American film scene.

The only legitimate Pyun comparisons I can think of are Italy’s Jess Franco (1930-2013) and Germany’s Ulli Lommel (1944-2017), two filmmakers who boasted famous mentors—Orson Welles in Franco’s case and Rainer Werner Fassbinder in Lommel’s—and, after wowing the world with early features—Franco with THE AWFUL DR. ORLOFF/ Gritos en la noche (1962) and Lommel with TENDERNESS OF THE WOLVES/ Die Zärtlichkeit der Wölfe (1973)—settled into steady careers in the trash movie sphere. Both men, it’s widely believed, were fully capable of holding their own with the big boys, yet Franco and Lommel seemed more comfortable ensconced in the industry’s skuzzier regions.

As with those guys, Albert Pyun burst onto the scene with a buzzy film, 1983’s SWORD AND THE SORCEROR, yet spent the majority of his career in the grade-Z sphere. Also like Messrs. Franco and Lommel, Pyun was mentored by a world-renowned master, in this case Akira Kurosawa—albeit only briefly, as the teenaged Pyun was summoned to Japan in the early 1970s by Toshiro Mifune, who was set to headline Kurosawa’s DERSU UZALA (1975). When Mifune’s involvement in that film was nixed Pyun went to work at Mifune Productions, where he assisted the legendary cinematographer Takao Saito—about which Pyun later admitted “I was a bit lost initially. Some would say I still am!”

Back in the US, Pyun wasted no time establishing himself as the King of the B’s. He worked with many of the big names in the exploitation sphere of the late eighties and nineties, including Menahem Golan (who Pyun described as “Fun. Crazy. And LOUD!”) and Charles Band (“we never saw eye to eye on the films…He wants them to adhere to his specific concept of brand and style. But I was never one to adhere to anything”).

I’ve long believed Pyun would have thrived in the independent film revolution of the nineties, much like Canada’s Rafal Zielinski. He, like Pyun, was a well-trained art film aficionado who throughout the 1980s found himself stuck making exploiters, such as SCREWBALLS (1983) and VALET GIRLS (1986); but then in 1994 Zielinski did what so many other mid-nineties indie auteurs were doing, and put together a no-budget art film. That film, called FUN, afforded its underappreciated director some welcome critical attention and a brief theatrical run, although it didn’t bring in much (if any) money.

The fiscal uncertainty of independent filmmaking explains, in part, why Pyun spurned arthouse fare in favor straight-to-video programmers like the New Moon production DOLLMAN (1991), the Rutger Hauer vehicle OMEGA DOOM (1996) and the “Charles” Sheen thriller POSTMORTEM (1998): he had a full awareness of the financial realities of the film business. Pyun made sure never to overspend on his films, and always stuck to commercially proven genres—although it certainly helped matters that his favored categories were science fiction and action, and that (again like Messrs. Franco and Lommel) he evidently prized quantity over quality.

DOLLMAN (1991), the Rutger Hauer vehicle OMEGA DOOM (1996) and the “Charles” Sheen thriller POSTMORTEM (1998): he had a full awareness of the financial realities of the film business. Pyun made sure never to overspend on his films, and always stuck to commercially proven genres—although it certainly helped matters that his favored categories were science fiction and action, and that (again like Messrs. Franco and Lommel) he evidently prized quantity over quality.

Reviewing Pyun’s filmography, I find THE SWORD AND THE SORCERER, involving a magic sword, an undead necromancer and an evil king, a standout. It suffers from poor storytelling (a frequent Pyun movie complaint) and production values that often evidence the low budget all too clearly, but overall it’s a worthy entry* in the sword and sorcery movie craze of the early 1980s, and holds up better than most of the others (SORCERESS, THE BEASTMASTER, CONQUEST, DEATHSTALKER, etc.). I’m also partial to Pyun’s second feature RADIOACTIVE DREAMS (1984), a punk-fueled post-apocalyptic actioner that set the tone for what was to come from this consistently unpredictable auteur.

Pyun’s Cannon production DANGEROUSLY CLOSE (1986), an eighties-centric MASSACRE AT CENTRAL HIGH wannabe, was uninspired, and the Jean Claude Van Damme vehicle CYBORG (1989), which was thrown together after a proposed MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE sequel was shuttered, wasn’t much better in my view (although it is beloved by Pyun aficionados). Pyun, incidentally, put out a CYBORG director’s cut DVD in later years that was packaged in typical Pyun fashion: as a crudely Xeroxed copy of the official MGM DVD release with a handwritten “Director’s Cut” moniker scrawled across the top.

Of the 1990 CAPTAIN AMERICA, Pyun himself has dismissed it as “a train wreck right from the start,” it being a film whose only saving grace is that it wasn’t quite as horrendous as the decade’s other major comic book low budgeter (yes, back then that was the form comic book adaptations tended to take), the Roger Corman produced FANTASTIC FOUR (1994). Far superior is NEMESIS (1992), a sleek and stylish take on themes from THE TERMINATOR (1984) and ROBOCOP (1987) that was strong enough to score a (brief) theatrical release.

Following the turn of the millennium Pyun’s films took on an increasingly gonzo air. Created with the help of his screenwriter wife Cynthia Curran, those post-2000 films were by and large digitally lensed, with no funds to speak of (2010’s BULLETFACE was shot in a reported five days on a $100 thousand budget), and often made on a whim. ROAD TO HELL (2008), for instance, came about due to an argument between Pyun and Curran about Walter Hill’s “Rock ‘n’ Roll Fable” STREETS OF FIRE (1984), the ending of which Pyun found deeply romantic. Curran disagreed, leading her to write the film, an uncredited sequel (that proclaimed itself “Still a Rock ‘n’ Roll Fable”) to Hill’s film that Pyun stocked with its original cast members Michael Pare and Deborah Van Valkenburgh. Note also ROAD TO HELL’s end credits, which make sure to inform us that it’s “Albert Pyun’s 50th Movie” (something that appears to have inspired Quentin Tarantino).

Following the turn of the millennium Pyun’s films took on an increasingly gonzo air. Created with the help of his screenwriter wife Cynthia Curran, those post-2000 films were by and large digitally lensed, with no funds to speak of (2010’s BULLETFACE was shot in a reported five days on a $100 thousand budget), and often made on a whim. ROAD TO HELL (2008), for instance, came about due to an argument between Pyun and Curran about Walter Hill’s “Rock ‘n’ Roll Fable” STREETS OF FIRE (1984), the ending of which Pyun found deeply romantic. Curran disagreed, leading her to write the film, an uncredited sequel (that proclaimed itself “Still a Rock ‘n’ Roll Fable”) to Hill’s film that Pyun stocked with its original cast members Michael Pare and Deborah Van Valkenburgh. Note also ROAD TO HELL’s end credits, which make sure to inform us that it’s “Albert Pyun’s 50th Movie” (something that appears to have inspired Quentin Tarantino).

Unfortunately the disjointedness of Pyun’s filmmaking didn’t improve with this new direction—just the opposite, in fact. In INFECTION (2005) it seems as if Pyun was more interested in the idea of a continuous take than he was in telling a coherent story, and in the H.P. Lovecraft adaptation COOL AIR (2006) he appeared plain disinterested. Pyun was known to have been suffering from dementia for some time prior to his demise, and these films would appear to offer solid proof that not all was well with this much-missed iconoclast, about whom a detailed biography is long overdue.