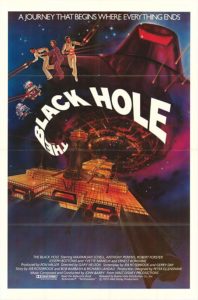

The following was inspired by the 2016 publication 70s MONSTER MEMORIES, consisting of nostalgic celebrations of 1970s-era genre films. I was in single digits during the seventies, and so remember very little of the decade or its movies (I have no memory of seeing STAR WARS a first, or even second, time) but for one isolated example: THE BLACK HOLE, a Walt Disney production released in December of 1979.

The following was inspired by the 2016 publication 70s MONSTER MEMORIES, consisting of nostalgic celebrations of 1970s-era genre films. I was in single digits during the seventies, and so remember very little of the decade or its movies (I have no memory of seeing STAR WARS a first, or even second, time) but for one isolated example: THE BLACK HOLE, a Walt Disney production released in December of 1979.

For me THE BLACK HOLE was a pivotal film. I retain vivid memories of my initial viewing in December of ‘79, and of catching up with it on HBO a year or two later. It can be pinpointed as the first of my innumerable pop culture obsessions, even though the movie itself is a negligible product at best.

In fact, THE BLACK HOLE was something of an anomaly amid the flood of STAR WARS rip-offs that proliferated at the end of the 1970s, being a philosophically-minded product with more talk than action. It began life in 1974, as a screenplay entitled SPACE STATION-ONE that was subjected to the soul-crushing grind that is the Hollywood development process. Initially set to be directed by John Hough, SPACE STATION-ONE’s initial drafts were black hole-less. At some point a black hole was added, and by the time the film went into production in 1978, under the direction of FREAKY FRIDAY’S Gary Nelson, said hole has grown to dominate the narrative and the title.

As it turned out, the black hole was the most interesting element of the finished film, which is essentially an outer space variant on TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA. Standing in for Captain Nemo is Hans Reinhardt (played by a slumming Maximillian Schell), a brilliant scientist who’s residing in the Cygnus, a massive spaceship manned by emotionless robots—actually zombified humans—that’s stationed at the edge of a black hole. Real black holes are invisible, but the one depicted here is a swirling multicolored whirlpool (no wonder astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson dubbed THE BLACK HOLE “the least scientifically accurate movie of all time”).

Also turning up are Robert Forster, Anthony Perkins, Joe Bottoms, Ernest Borgnine and Yvette Mimieux as cosmonauts aboard the Palomino space  cruiser, which happens upon the Cygnus. Mimieux has a special interest in the ship, as her father disappeared in connection with it years earlier, but that plot strand is quickly dropped. Far more attention is lavished on Vincent, a cute floating robot, and Old Bob, a much older, beaten-up version of Vincent, as well as Maximillian, a scary blood-red ‘bot who accompanies Reinhardt—and also the special effects, which were quite elaborate and ground-breaking for their day.

cruiser, which happens upon the Cygnus. Mimieux has a special interest in the ship, as her father disappeared in connection with it years earlier, but that plot strand is quickly dropped. Far more attention is lavished on Vincent, a cute floating robot, and Old Bob, a much older, beaten-up version of Vincent, as well as Maximillian, a scary blood-red ‘bot who accompanies Reinhardt—and also the special effects, which were quite elaborate and ground-breaking for their day.

Budgeted at $20 million (an extremely pricey sum back in ‘79; STAR WARS cost roughly half that), THE BLACK HOLE was the most expensive film in Disney’s history. It was the premiere attempt by Disney at navigating a new, more adult-oriented course, being its first-ever PG rated movie. This reportedly resulted in a deluge of hate mail (and resulted in the second PG rated Disney flick, the 1980 comedy MIDNIGHT MADNESS, being released without the Disney logo, and the formation of Touchstone Pictures five years later).

That PG rating was due, apparently, to a few instances of bad language (example: “What the Hell are you made of?”) and the “intensity” that occurs in the final twenty minutes. Those final scenes are, in true 1970s-era Disney fashion, taken up with action, specifically a lot of shooting and explosions (in place of the lackluster car chases that concluded FREAKY FRIDAY and THE MILLION DOLLAR DUCK)—albeit scored by John Barry’s slow and magisterial theme music, which doesn’t exactly jibe with all the smoke and laser beams.

The trippy ending, in which everybody finally makes their way into the black hole, was very evidently inspired by the star gate sequence of 2001. I think it goes without saying that THE BLACK HOLE’s star gate is a far lesser achievement, although the scene depicting Reinhardt and Maximillian in Hell is a striking one (particularly in a Disney movie!). The crew of the Palomino, meanwhile, travel through an angelic hallway—a white hole, apparently—and wind up heading toward an especially bright star. Precisely what happens here I don’t know, and neither, evidently, did anyone else on THE BLACK HOLE’S crew.

Just check out the divergent endings of THE BLACK HOLE novelization, which concludes with the Palomino’s crew becoming a single conjoined entity after their physical bodies are dissolved, and the read-long audio version, in which said crew is faced with “whole planets and stars that had been swallowed by the black hole,” thus offering them a wide range of potential habitations. Yet another conclusion is provided by the BLACK HOLE pop-up book, which ends with the protagonists entering the “swirling unknown of” the black hole.

That latter point brings up a most important element of the BLACK HOLE saga: the merchandising, upon which Disney went all out. One of George Lucas’s smartest moves in making STAR WARS was retaining the merchandising rights, which was considered an odd choice back in 1977. Disney made sure to follow his lead by putting out a plethora of toys and tie-in material, of which I long believed I owned every conceivable permutation. As it turns out, I barely scratched the surface.

Among my collection were the BLACK HOLE action figures from Mego, which included Vincent, Old Bob and Maximillian figurines, all of which were quite cool (the human figures not so much). Ditto the BLACK HOLE pop-up book, consisting of painted recreations (for which no artist is credited) of the film’s imagery, enhanced by pull tabs and pop-up displays.

Among my collection were the BLACK HOLE action figures from Mego, which included Vincent, Old Bob and Maximillian figurines, all of which were quite cool (the human figures not so much). Ditto the BLACK HOLE pop-up book, consisting of painted recreations (for which no artist is credited) of the film’s imagery, enhanced by pull tabs and pop-up displays.

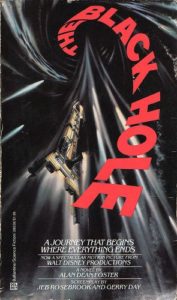

Other BLACK HOLE ephemera I owned included the aforementioned read-long version, consisting of a booklet and a record that narrates the story together with dialogue and sound effects from the film; of it there’s little to be said outside the alternate ending mentioned above (and the fact that I got a royal ass-chewing from my first grade teacher for listening to it during class). THE BLACK HOLE STORYBOOK is about on the same level, being a perfunctory recounting of the events of the film accompanied by a generous selection of stills. Then there’s the Alan Dean Foster novelization, which deserves a more in-depth examination.

As with most Alan Dean Foster movie novels (Foster ghost wrote most if not all of the bestselling STAR WARS novelization) his rendering of THE  BLACK HOLE is far classier than the material deserves. Foster never succeeds in overcoming the thinness of the narrative, but he does attempt to add some character shading and scientific detail. This unfortunately has the effect of rendering a boring story even more so (it takes sixty pages, for instance, for the crew of the Palomino to make their way onto the Cygnus). Another problem is with the fact that the film’s visual design evidently wasn’t complete when Foster wrote this book, resulting in some cut-rate descriptions. This tendency is most noticeable in the detailing of Vincent, Old Bob and Maximillian, who are never described in much depth. The final pages, at least, conveying what happens when the Palomino’s crew makes its inevitable way into the black hole and out the other side (see above), are genuinely trippy, reading like excerpts from BAREFOOT IN THE HEAD.

BLACK HOLE is far classier than the material deserves. Foster never succeeds in overcoming the thinness of the narrative, but he does attempt to add some character shading and scientific detail. This unfortunately has the effect of rendering a boring story even more so (it takes sixty pages, for instance, for the crew of the Palomino to make their way onto the Cygnus). Another problem is with the fact that the film’s visual design evidently wasn’t complete when Foster wrote this book, resulting in some cut-rate descriptions. This tendency is most noticeable in the detailing of Vincent, Old Bob and Maximillian, who are never described in much depth. The final pages, at least, conveying what happens when the Palomino’s crew makes its inevitable way into the black hole and out the other side (see above), are genuinely trippy, reading like excerpts from BAREFOOT IN THE HEAD.

Other BLACK HOLE merchandise, which I didn’t own, included a limited edition comic book series called BEYOND THE BLACK HOLE, frame tray and jigsaw puzzles, lego sets, board games, activity books, “colorforms” sets (in which cut-out figures were provided to be pasted onto backgrounds from the movie), hand-cranked movie viewers, calendars, pencil holders, lunch boxes, trading cards and model kits that now go for triple digit figures on eBay.

Today, of course, I no longer own much of anything that’s BLACK HOLE associated. It seems the obsession that gripped my younger self has finally and definitively worn off, and I can see THE BLACK HOLE for what it is: a bad movie in whose place you’d be much better off watching STAR WARS again.