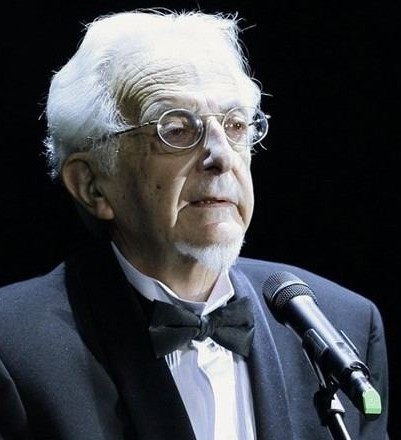

Here (for once) is a commentary about a director whose work doesn’t particularly excite me: Mexico’s late Rafael Corkidi (1930-2013).

Here (for once) is a commentary about a director whose work doesn’t particularly excite me: Mexico’s late Rafael Corkidi (1930-2013).

Corkidi, of course, was best known as a cinematographer, and I’ll be the first to admit his prodigious talent for lighting and composition bordered on genius. It’s appropriate, then, that Corkidi remains best known for four films he photographed but didn’t direct. Regarding the features he did helm, the best I can say about them is that all are extremely well visualized.

Corkidi’s photography was the main asset of the experimental ANTICLIMAX (1969), the first and only feature by the famed poet/artist Gelson Gas. While ANTICLIMAX’S overall sensibility belongs to Gas, it was Corkidi who provided the impressively textured black-and-white imagery (women’s bare legs crossing and uncrossing aboard a bus, the protagonist going nuts in a supermarket, etc.) that’s so vital to the film’s kaleidoscopic depiction of 1960s-era Mexico.

The Alexandro Jodorowsky films EL TOPO (1970) and THE HOLY MOUNTAIN (1973) and Juan Lopez Moctezuma’s MANSION OF MADNESS (1973) likewise benefited immeasurably from Corkidi’s visuals. The desert-set EL TOPO in particular bears Corkidi’s fingerprints in its impeccably visualized surreal set pieces that directly foreshadow his self-directed features. Corkidi’s work on THE HOLY MOUNTAIN, alas, was apparently marred by friction with Jodorowsky, who claims that Corkidi “was a nice person when we made EL TOPO…then when we made THE HOLY MOUNTAIN he was very difficult to control,” and alleges Corkidi even tried to “sabotage” the film. As for THE MANSION OF MADNESS, Corkidi’s bold cinematography was integral to that film’s overpowering aura of surreal insanity.

Of Corkidi’s self-directed features, Jodorowsky has claimed they were all directly inspired by EL TOPO and dismissed them as “boring.” I’m not entirely sure I agree with the first statement, as Corkidi clearly had a style and point of view that were very much his own (although at least one of his films does owe a sizeable debt to Jodorowsky), yet on the second Jodorowsky is entirely correct, as boring is something the following films indisputably are.

ANGELS AND CHERUBS (ANGELES Y QUERUBINES; 1972) was the first and most famous feature directed by Mr. Corkidi. It begins with a hallucinatory take on Adam and Eve featuring two naked children frolicking in a beachfront Eden. From there the action switches to the interior of a dark castle where a young man falls in love with an alluring gal who comes from a staunchly middle-class family living nearby, which leads to disillusionment, death and vampirism.

Quite simply, the film is a bore. Virtually every scene is allowed to drag on far longer than is necessary, regardless of how uneventful those scenes may be (watching a servant woman endlessly circle a dinner table doling out soup is about as interesting as it sounds), and there’s little in the way of a cogent narrative to hold it all together. The film is crammed with striking surreal touches (telepathic puppets, an elaborate religious procession in the middle of a parched desert), but they feel gratuitous. Yet the cinematography, accomplished by Corkidi himself, is stunning.

ANGELS AND CHERUBS was followed by ONE WHO CAME FROM HEAVEN (AUANDAR ANAPU; 1974), a religious allegory about a saintly man wandering through a desert landscape, breaking up fights, fucking women and getting in trouble with the authorities. The proceedings are notable for the fact that the characters all have a tendency to break into music numbers in which they lip-synch to old Spanish tunes.

Corkidi evidently had EL TOPO in mind, even though the film was allegedly based on a Mexican folk tale. Also, the surrealism usually so integral to Corkidi’s style was toned down, leaving us with an impressively photographed but quite tedious effort.

PAFNUCIO SANTO (1977) features a young boy in a football jersey wandering through a(nother) surreal desert landscape, where he encounters several famous individuals, among them Frieda Kahlo, Hernando Cortez, Patty Hearst and Emilio Zapata (in the guise of an attractive woman), all of whom (as in the previous film) frequently lip synch to  famous operas. Once again, the visuals are damned impressive, but the film is a half-baked, uneventful snooze.

famous operas. Once again, the visuals are damned impressive, but the film is a half-baked, uneventful snooze.

Finally, we have DESEOS (1978) which treads the same ground as the previous three entries. As in ANGELS AND CHERUBS, the setting is a desert manor that houses a singularly freaky band of eccentrics; as in PAFNUCIO SANTO, all the characters periodically break into song, lip syncing to old Mexican tunes regardless of gender; as in ONE WHO CAME FROM HEAVEN, there’s a heavy religious subtext, with a constantly masturbating nun and a plethora of crucifixion imagery. Corkidi’s visuals, as always, are eye-popping, consisting of a succession of impeccably lit and composed wide shots, but in all other aspects the film, in what had become an all-too-common aspect of Corkidi’s work, is a pretentious dirge.

Most of the remainder of Corkidi’s filmography consisted of TV documentaries and a handful of little-seen features (including 1984’s long-banned FIGURAS DE LA PASION, 1992’s RULFO AETERNUM and 2010’s EL MAESTRO PRODIGIOSO). Corkidi can unquestionably be viewed as one the greatest cinematographers Mexico produced; his skills as a director, alas, were not in the same league.