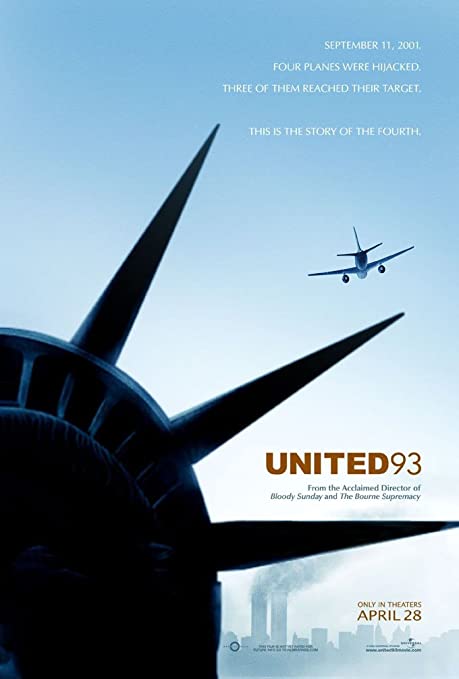

“Too soon!” As you may recall, that was the oft-quoted April 2006 refrain shouted by irate movie theater patrons upon viewing teaser trailers for UNITED 93. The film was a dramatization of the events of September 11, 2001, when two planes, hijacked shortly after takeoff by Islamic terrorists under the direction of Osama Bin Laden, flew into and destroyed the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, while a third hit the Pentagon and a fourth (the subject of UNITED 93) crashed in a Pennsylvania field. Interpretations of the event, artistic and otherwise, were inevitable, and by 2006, contrary to what the above-mentioned moviegoers seemed to believe, the media landscape was positively saturated with September 11 themed movies, books, television and music.

“Too soon!” As you may recall, that was the oft-quoted April 2006 refrain shouted by irate movie theater patrons upon viewing teaser trailers for UNITED 93. The film was a dramatization of the events of September 11, 2001, when two planes, hijacked shortly after takeoff by Islamic terrorists under the direction of Osama Bin Laden, flew into and destroyed the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, while a third hit the Pentagon and a fourth (the subject of UNITED 93) crashed in a Pennsylvania field. Interpretations of the event, artistic and otherwise, were inevitable, and by 2006, contrary to what the above-mentioned moviegoers seemed to believe, the media landscape was positively saturated with September 11 themed movies, books, television and music.

The media-centric nature of the event and its aftermath is evident in all the new and/or renamed terminology that entered the lexicon, including “Ground Zero” and “9/11” (a set of digits which after that date meant something very different than they did before). Note also a crack made by Howard Stern about how previous generations reacted to attacks on their country by joining the military, whereas when 9/11 happened people “ran into their basements” to record crappy songs. Those songs, naively patriotic affairs, were lampooned quite adroitly in the 2004 flick TEAM AMERICA (whose soundtrack included the immortal lyric “America, fuck yeah!”).

Hollywood’s initial response was to obfuscate any and all references to the World Trade Center, the Pentagon or just about anything that might recall the events of 9/11 (hence the title of a 2002 article I wrote for Gauntlet magazine: “September 11: A Great Day for Censors”). Scenes from SPIDERMAN showing the Twin Towers were edited out, a terrorist subplot was removed from the Arnold Schwarzenegger actioner COLLATERAL DAMAGE, the WTC set climax of the MEN IN BLACK II script was rewritten, and writer-director Francis Ford Coppola’s planned filming of his long gestating dream project MEGALOPOLIS was cancelled due to the fact that the script contained scenes of NYC menaced by falling moon rocks. Those were but a few examples of what the French author Frédéric Beigbeder proclaimed “a spontaneous omertà, a media blackout unprecedented since the first Gulf War.” This was Hollywood’s idea of responsibility, although a more accurate (and up-to-date) term would be virtue signaling.

Among the bolder Hollywoodians were Martin Scorsese, who ended his 2002 film GANGS OF NEW YORK with a shot of the still-standing Twin Towers, and Spike Lee, who in THE 25th HOUR (also from ‘02) included extensive footage of the Tribute of Light (twin spotlights shown upward where the WTC towers previously stood). Such flourishes might not seem especially daring or courageous, but given the climate of time I’d say they were.

In many respects the early oughts were a direct precursor to the “woke” era in the unprecedented suppression exercised by media gatekeepers. Old movies were given renewed scrutiny (such as 1970’s LOVING, which showed the WTC being built, and the 1976 KING KONG, whose climax took place atop the Twin Towers) and harsh punishments were dealt out to those who didn’t treat 9/11 with the utmost solemnity, with self-appointed online enforcers tasked with keeping us all in line. The media’s rightward political leaning was obviously quite different than that of today, but the repressive atmosphere was much the same.

Among the anti-9/11 transgressors was Robert De Niro, who was widely criticized for appearing in a Martin Scorsese directed American Express commercial that contained footage of Ground Zero—which was dubbed exploitive in the context of a shill for AmEx (a major sponsor of De Niro’s Tribeca Film Festival). De Niro, however, fared far better than Bill Maher, who on the September 17, 2001 episode of his ABC program POLITICALLY INCORRECT (one of whose scheduled guests, the late political commentator Barbara Olson, was aboard the hijacked plane flown into the Pentagon)  made the mistake of proclaiming the 9/11 hijackers courageous; the program, following advertising boycotts and mass condemnation, was cancelled in June of ‘02, forcing Maher back to where POLITICALLY INCORRECT began: cable TV.

made the mistake of proclaiming the 9/11 hijackers courageous; the program, following advertising boycotts and mass condemnation, was cancelled in June of ‘02, forcing Maher back to where POLITICALLY INCORRECT began: cable TV.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was the French who, as enumerated in a September 2003 The New York Times article, were the first to deal with 9/11 head-on. Free from the restrictions placed on American media, Francophone attitudes toward the tragedy, as you might guess, were complex.

By 2003 no less than five 9/11-themed French language books had appeared. They included the novel THE DAY I RETURNED TO EARTH by Didier Goupil, the nonfiction screed 11 SEPTEMBER, MON AMOUR by Luc Lang, the children’s book NINE ELEVEN by Jean-Jacques Grief, the graphic novel TRIBECA SUNSET by Henrik Rehr, and WINDOWS ON THE WORLD, a quasi-fictional rumination by Frédéric Beigbeder. Only the latter two were translated into English, with TRIBECA SUNSET emerging as one half of an effective book.

This is to say that TRIBECA SUNSET’s first half, depicting the actual 9/11 experiences of its author/illustrator, who lived across the street from the WTC, is riveting. This portion was published by itself in its original 2002 French language version (entitled MARDI 11 SEPTEMBRE), and that’s how it should have been packaged in English. Depicted is the chaotic evacuation process that took place in NYC, with Rehr, separated from his wife and son, ferrying across the Hudson River with his infant child in tow, and flashing back upon important events in his life. Rendered in Charles Burns-ian black and white drawings, the tale Rehr relates may not be the most exciting one to come out of 9/11, but it has the undeniable charge of reality—and so all-but obliterates the book’s fictional second half, in which several friends get together several years after 9/11 to discuss its effects on them.

Frédéric Beigbeder was one of the small but vocal contingent of French “anti-anti-Americans” who made their voices heard in the wake of 9/11. He claimed to have written WINDOWS ON THE WORLD “because I am sick of French anti-Americanism,” and also because “In the face of American self-censorship, I wanted to give form to this tragedy.”

claimed to have written WINDOWS ON THE WORLD “because I am sick of French anti-Americanism,” and also because “In the face of American self-censorship, I wanted to give form to this tragedy.”

WINDOWS ON THE WORLD takes the form of a minute-by-minute (with each of its chapters taking place over the course of a single minute) depiction of the tragedy of 9/11 from 8:30 AM to 10:29 AM. The main characters are the fictional Carthew Yorston, a wealthy American divorcee who on the morning of September 11, 2001 finds himself and his two young sons in the WTC’s top floor restaurant Windows on the World, and Beigbeder himself, who airs his attitudes toward 9/11 while breakfasting in the Ciel de Paris restaurant atop the Parisian skyscraper Tour Montparnasse. Thus the horror of Yorston’s account, in which he and his sons are subjected to fire, smoke inhalation and, inevitably, death, is mitigated somewhat by Beigbeder’s nonfictional musings in a book’s both visceral and intellectual, with the latter attribute ultimately winning out.

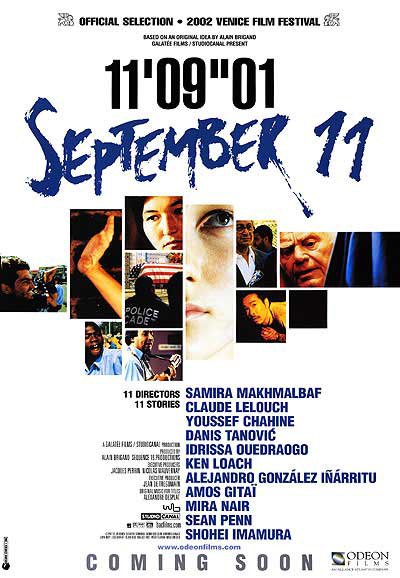

France was also responsible for the anthology feature SEPTEMBER 11, completed in 2002. It showed the reactions of various filmmakers around the world to 9/11 in films that each lasted 11 minutes, 9 seconds and one image (get it?). Among the filmmakers were Iran’s Samira Makhmalbaf, Israel’s Amos Gitai, India’s Mira Nair, Japan’s Shohei Imamura, France’s Claude Lelouch and Egypt’s Youssef Chahine, who in a film about a zombie recounting how he was killed by Americans years earlier kicks off of a theme that’s quite prevalent in this project: the indicting of America for its past crimes.

Filmmaker Danis Tanovic has a woman learning of the WTC attacks and then joining a protest march, while England’s Ken Loach provides an insulting ramble about a Chilean man writing a letter to 9/11 survivors describing how the US sponsored an invasion of his homeland years earlier. Alejandro Gonzalez’s Inarritu segment is an impressionistic evocation of sounds and images that was clearly made to be experienced on a big screen, and really doesn’t work too well on TV (which is unfortunately how I viewed it). America’s own Sean Penn offers a downright infuriating film with Ernest Borgnine as a NYC based widower finding that the collapse of the Twin Towers lets in sunlight that causes a pot of dead flowers to grow again.

As the staunchly liberal Roger Ebert questioned in his review, “Would it have killed one of these 11 directors to make a clear-cut attack on the terrorists themselves?” Blame the film’s producer Alain Brigand, who was primarily responsible for SEPTEMBER 11’s overall thrust. Among the filmmakers he turned down was the NYC based Abel Ferrara, whose proposed contribution, a tribute to the New Yorkers who died (many of whom Ferrara knew personally) that was to be related via a mixture of verite footage and staged drama, lacked the ironic distancing and/or smug anti-Americanism that appeared to have been Brigand’s intent.

As the staunchly liberal Roger Ebert questioned in his review, “Would it have killed one of these 11 directors to make a clear-cut attack on the terrorists themselves?” Blame the film’s producer Alain Brigand, who was primarily responsible for SEPTEMBER 11’s overall thrust. Among the filmmakers he turned down was the NYC based Abel Ferrara, whose proposed contribution, a tribute to the New Yorkers who died (many of whom Ferrara knew personally) that was to be related via a mixture of verite footage and staged drama, lacked the ironic distancing and/or smug anti-Americanism that appeared to have been Brigand’s intent.

The French, however, did turn out one indisputably great 9/11 related work: a documentary entitled 9/11 that was broadcast on CBS on March 10, 2002. The film, which contains narration by Robert De Niro and some staged footage (as indicated by a much-remarked-upon scene in which the attack on the Pentagon is discussed in plain view of a clock reading 9:30, when the Pentagon wasn’t actually hit until seven minutes later), can be termed American made, yet the majority of its footage was created by the French documentarians Jules and Giddeon Naudet. They were making a documentary about NYC firefighters that ended up as something else entirely when one fateful morning they unexpectedly filmed a plane flying into the World Trade Center.

What follows takes us from the bottom floor of Tower One—the only known footage of the WTC lobby on 9/11—to the streets of NYC as they’re blanketed with dust, to the devastation on 9/12, when fire fighters were tasked with sifting through the rubble in 24 hour shifts. The film is an astonishing piece of work, and the closest thing that exists to a definitive documentation of what occurred in New York City on 9/11 (of the Pentagon and United 93 attacks, alas, no such filmings exist).

It took until 2004 for the United States to fully engage with the events of 9/11, in the unabashedly left-leaning, politically minded documentary FARENHEIT 9/11. The film proved quite popular, winning the Palm D’Or at Cannes—according to jury member Kathleen Turner, “I really thought the Korean film entry (OLDBOY) was more powerful as a film (but) I was outvoted”—and raking in over $200 million, making it the most lucrative documentary ever (a title it still holds).

The film was an all-out attack on President George W. Bush by director/star Michael Moore, who had already called out Bush onstage at the 2003 Oscars telecast. Here Moore deepened his critique, showing how thousands of black peoples’ votes were “lost” by Florida authorities in the ‘00 election, how the Bush family had suspicious ties to the Bin Ladens, and how the 2003 instituted War in Iraq did very little to help the people of that country or thin the terrorists’ ranks. Yet there were many questionable elements, such as a montage showing happy, contented Iraqis going about their lives in the days before the bombs hit, that upset conservatives and liberals alike.

Yes, there was a time when fairness in media coverage was prized by both political parties, as evinced by the reaction to TEAM AMERICA: WORLD POLICE. It was a satiric marionette movie from SOUTH PARK’S Trey Parker and Matt Stone that took on the War on Terror that followed 9/11, via a “Team America” who fly around the world, righting wrongs by blowing things up. This allowed Parker and Stone to take a number of on-target swipes at American right wing machismo, and also left-leaning celebrities like Susan Sarandon, Alec Baldwin, Ben Affleck, etc. Believe it or not, critics of the time actually appreciated the skewering of both sides of the political aisle.

Yes, there was a time when fairness in media coverage was prized by both political parties, as evinced by the reaction to TEAM AMERICA: WORLD POLICE. It was a satiric marionette movie from SOUTH PARK’S Trey Parker and Matt Stone that took on the War on Terror that followed 9/11, via a “Team America” who fly around the world, righting wrongs by blowing things up. This allowed Parker and Stone to take a number of on-target swipes at American right wing machismo, and also left-leaning celebrities like Susan Sarandon, Alec Baldwin, Ben Affleck, etc. Believe it or not, critics of the time actually appreciated the skewering of both sides of the political aisle.

That even-handed approach wasn’t too popular with Hollywood in the ensuing years, but the focus on foreign wars definitely was. Note the string of liberal-minded Iraq War themed downers released during the years 2006-08, which included HOME OF THE BRAVE, BATTLE FOR HADITHA, RENDITION, REDACTED, STOP-LOSS and THE HURT LOCKER, which was awarded a Best Picture Academy Award even though it, like its fellows, made very little financial impression.

Perhaps the most interesting war movie of the period was YOUNG AMERICANS, a pro-Iraq War doco made by Hollywood agent-turned-conservative activist Pat Dollard. The picture was never completed (much less released), but it gained a fair amount of attention due to clips posted on YouTube (most of which appear to have been taken down). Contained is some truly hellacious battle footage, overlaid with a high-spirited, mischievous tone that stands in direct contrast to the obnoxiously somber bent of RENDITION and THE HURT LOCKER. An attempt was made to turn Dollard into a “conservative Michael Moore,” but as he and his debauched lifestyle made Hunter S. Thompson look like a choirboy (as chronicled in a 2007 Vanity Fair article that was optioned for film by the late Tony Scott) that attempt was obviously doomed to failure, with both Dollard and YOUNG AMERICANS now forgotten, even by conservatives.

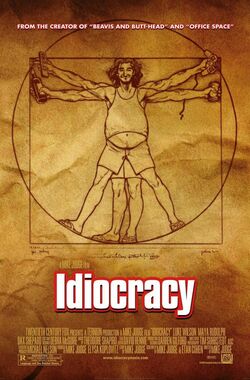

The best, and most accurate, political movie to emerge from the oughts was nearly as maligned: Mike Judge’s IDIOCRACY (2006), which got dumped by Fox, playing theatrically in less than ten cities with no promotion (I can recall checking for show times on websites that well into the film’s release termed it “UNTITLED MIKE JUDGE MOVIE”). About a future America whose populace has reverted to total idiocy, it’s funny and prophetic, and related to the above films by a climactic scene in which the heroine (Maya Rudolph) is seen painting a picture of the overseer of this society that, as a close-up reveals, is President George W. Bush—who was likewise skewered in Oliver Stone’s W. (2008), which featured Josh Brolin in a none-too-flattering GWB biofilm that was overlong and dull. In its place I’d recommend viewing IDIOCRACY, which provides a far more entertaining, and accurate, take on W.’s America.

The best, and most accurate, political movie to emerge from the oughts was nearly as maligned: Mike Judge’s IDIOCRACY (2006), which got dumped by Fox, playing theatrically in less than ten cities with no promotion (I can recall checking for show times on websites that well into the film’s release termed it “UNTITLED MIKE JUDGE MOVIE”). About a future America whose populace has reverted to total idiocy, it’s funny and prophetic, and related to the above films by a climactic scene in which the heroine (Maya Rudolph) is seen painting a picture of the overseer of this society that, as a close-up reveals, is President George W. Bush—who was likewise skewered in Oliver Stone’s W. (2008), which featured Josh Brolin in a none-too-flattering GWB biofilm that was overlong and dull. In its place I’d recommend viewing IDIOCRACY, which provides a far more entertaining, and accurate, take on W.’s America.

It was around that time, in early 2006, that the film mentioned at the head of this essay, UNITED 93, premiered, as well as a TV movie counterpart: FLIGHT 93. The latter, made for the A&E Network, contains many expected TVM shortcomings, including cut-rate special effects and overheated melodrama, but is an impressive accomplishment overall. Director Peter Markle (of HOT DOG…THE MOVIE and BAT 21) imparts the events that occurred on flight 93, when it was hijacked on 9/11/01, with great immediacy and a gut-level tension that begins in the opening scenes and doesn’t abate until the end credits roll.

Onto the Paul Greengrass directed UNITED 93, which furthers FLIGHT 93’s attributes. It can lay claim to being one of the greatest horror movies of all time in its pitiless depiction of ordinary people trapped in a confined space with a horror beyond imagining. Certainly the actions of United 93’s passengers, who (as portrayed here) precipitated a fight the resulted in the plane being crashed before it could reach the hijackers’ target, were heroic, but that doesn’t make their ultimate fate any less horrific.

UNITED 93, for all its virtues, is about as pleasant as a proctologic exam, an effect not helped at all by the Important Film designation bestowed upon it.  In a virtually unprecedented move, Universal insisted movie theaters show UNITED 93 without trailers or even (in the So Cal multiplex where I viewed it) Feature Presentation bumpers, with the lights going down and this Crucial Piece of Cinema allowed to unfold.

In a virtually unprecedented move, Universal insisted movie theaters show UNITED 93 without trailers or even (in the So Cal multiplex where I viewed it) Feature Presentation bumpers, with the lights going down and this Crucial Piece of Cinema allowed to unfold.

Such newfound boldness in Hollywood’s dealings with 9/11 resulted in another Oliver Stone film: WORLD TRADE CENTER, a fact based 9/11 account whose release trailed that of UNITED 93 by roughly three months. WORLD TRADE CENTER is in many respects a direct counterpoint, being extremely conservative in its approach, not to mention sentimental (the pic contains more weepy music cues and onscreen crying than any other 00s movie I can think of). Nonetheless, Stone gets some things right, such as his minute observance of the flow of life in New York City on the morning of September 11, and how within a couple minutes that flow was irrevocably transformed. Also impressive is the minimalistic depiction of the destruction of the Twin Towers, as seen from the vantage point of two firefighters (played by Nicolas Cage and Michael Peña) trapped in the WTC’s underground mall.

By 2008 the American public’s attitudes toward 9/11 had calmed enough that MAN ON WIRE, a documentary about Frenchman Philippe Petit’s 1974 stunt in which he leaped and danced on a tightrope strung between the Twin Towers, was distributed without incident, winning the Best Documentary Oscar. There followed THE WALK seven years later, a Robert Zemeckis directed 3-D dramatization of Petit’s exploits; the film’s major point of controversy, as I recall, was that its vertigo-inducing CGI visuals made viewers sick.

So laissez-faire had American’s attitudes to 9/11 become that in 2011 Hollywood finally did the unthinkable: it turned the event into Oscar-baiting inspiration porn. EXTREMELY LOUD AND INCREDIBLY CLOSE, based on a 2006 novel by Jonathan Safran Foer, was a movie that would have been slammed, and rightly so, had it been released five years earlier, but in ‘11 it received a wholly divergent (but equally justified) response: near-total indifference.

Starring Tom Hanks and Sandra Bullock, it centers on a precocious brat (Thomas Horn) whose father (Hanks) dies in the World Trade Center on 9/11. In its depiction of the fumbling efforts of the boy and his mother (Bullock) to make sense of the tragedy, the film contains a few genuinely perceptive moments amid an excess of gooey sentimentality, and grows downright repellent in the pompously redemptive final scenes, which bring to mind a rhetorical question posed about SCHINDLER’S LIST by critic J. Hoberman: “Is it possible to make a feel-good movie about the ultimate feel-bad experience of the century?”

That “feel-bad experience” had by the late 2010s become distant to the point of dreamlike abstraction. This was demonstrated in SHADOWBAHN by Steve Erickson, a surreal 2017 novel that contains dreamlike abstraction in abundance. Its subject: the Twin Towers, which appear intact one morning in South Dakota, emitting songs that vary depending on the listener, and containing a man on an upper floor who happens to be Jesse Presley, the brother of a famous figure bearing the same last name. For roughly its first hundred pages the novel is riveting, but loses its allure as it becomes clear that Erickson, an author one either “gets” or doesn’t (put me in the latter category), was making it up as he went along.

That “feel-bad experience” had by the late 2010s become distant to the point of dreamlike abstraction. This was demonstrated in SHADOWBAHN by Steve Erickson, a surreal 2017 novel that contains dreamlike abstraction in abundance. Its subject: the Twin Towers, which appear intact one morning in South Dakota, emitting songs that vary depending on the listener, and containing a man on an upper floor who happens to be Jesse Presley, the brother of a famous figure bearing the same last name. For roughly its first hundred pages the novel is riveting, but loses its allure as it becomes clear that Erickson, an author one either “gets” or doesn’t (put me in the latter category), was making it up as he went along.

From there we arrive full circle, at the twentieth anniversary of 9/11. There are no recent 9/11 themed movies to be found (aside from UNITED 93, which is in the midst of a theatrical rerelease), but there are some current books on the subject, including IN THE SHADOW OF THE FALLEN TOWERS by Don Brown, I SURVIVED THE ATTACKS OF SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 by Lauren Tarshis and Corey Egbert, and TALE OF TWO MARINES by James Buckley, Jr. and Andy Duggan. What these three books have in common is that all are aimed at young adult readers, suggesting it took two decades for us to answer a question—How do we explain 9/11 to the children?—that was widely asked back in 2001. Perhaps in another twenty years we’ll be able to finally come up with a fully satisfying artistic response to this tragedy, a wish no such response thus far has come close to fulfilling.