2010? It was a mediocre year for movies but for books it was a little better. Of course, most of my reading over the past year was far outside the mainstream. About high profile publications like Stephen King’s FULL DARK, NO STARS, China Meiville’s KRAKEN and Peter Straub’s A DARK MATTER I can’t tell you much, but can fill you in on quite a few lesser-known but equally worthy (if not more so!) publications.

Bear Manor Media

One publisher whose 2010 output was particularly (and unexpectedly) worthy was BearManor Media. They tend to specialize in film-related books but occasionally venture outside that realm. Two such examples were AND NOW THE NIGHTMARE BEGINS: THE HORROR ZINE and TWICE THE TERROR: THE HORROR ZINE Volume 2, both edited by JEANI RECTOR, and both consisting of stories, poems and artwork culled from Rector’s Horror Zine website.

One publisher whose 2010 output was particularly (and unexpectedly) worthy was BearManor Media. They tend to specialize in film-related books but occasionally venture outside that realm. Two such examples were AND NOW THE NIGHTMARE BEGINS: THE HORROR ZINE and TWICE THE TERROR: THE HORROR ZINE Volume 2, both edited by JEANI RECTOR, and both consisting of stories, poems and artwork culled from Rector’s Horror Zine website.

Short stories comprise the first and most substantial portion of AND NOW THE NIGHTMARE BEGINS, followed by 49 pages of poetry. Of the stories, the standouts for me were “The Real-Time Boogey Man” by Chris Castle, a haunting and poetic account of a ghostly Halloween encounter; “The Pass” by Simon Clark, about an apocalyptic landscape invaded by a swarm of apparent monsters that turn out to be something else entirely; and “The Rattling Man” by Alan Draven, a nasty little number about “the meanest of the boogeymen” and the impact it has on a young boy. I also got a kick out of Rector’s own “Cockroaches,” an insect-themed spine-tingler in the grand tradition of Thomas M. Disch’s “The Roaches” and Oscar Cook’s “Caterpillar.”

As for the poetry, it’s divided into twelve chapters showcasing 4-5 poems for each author. My favorites were the darkly humorous poems of Dennis Bagwell, particularly “If Frankenstein’s Monster Were Alive Today” and “The Itch,” about a terrible itch that leads to psychosis and mutilation. I’ll admit my bias when it comes to the work of Joe R. Lansdale (a longtime favorite), but I really liked his gruff, hard-bitten poetry. I’m not as familiar with the work of Juan Manuel Perez, but his poems are powerful evocations of death and foreboding. Another of the book’s standout poets is Scott Urban: I guarantee you’ll have a difficult time shaking his poem “Your maggot,” which concludes with the immortal lines “you don’t have to be dead/for me to get under your skin.”

TWICE THE TERROR is even stronger overall than Volume 1. “It’s A Boy” by David Bernstein starts things off in  suitably nasty fashion, detailing what transpires when a pregnant woman dies in the midst of a zombie outbreak. Christopher Fowler provides “The Threads,” a skin-crawler about a truly hideous revenge visited on an English tourist in North Africa. For those with a taste for the surreal there’s the slip-streamy “Who?” by the 1960s-era small press legend Hugh Fox, while those wanting an old-fashioned monster tale will appreciate “Soul Money” by Terry Grimwood.

suitably nasty fashion, detailing what transpires when a pregnant woman dies in the midst of a zombie outbreak. Christopher Fowler provides “The Threads,” a skin-crawler about a truly hideous revenge visited on an English tourist in North Africa. For those with a taste for the surreal there’s the slip-streamy “Who?” by the 1960s-era small press legend Hugh Fox, while those wanting an old-fashioned monster tale will appreciate “Soul Money” by Terry Grimwood.

The best stories, in my view, are “Erasure” by Sandhya Falls, a highly resonant account of the anxiety and apprehension experienced by a woman slowly becoming invisible; “Emma Baxter’s Boy” by Ed Gorman, a spare and unforgiving look at a mutant child and its parents’ attempts at keeping it safe; “The Security System” by Bentley Little, which presents the reality-based frustrations of Little’s novels in admirably compact form; “Underbed” by Graham Masterton, a fun tale in which a boy enters a wondrous and horrific universe through his bed; and the hallucinatory “In Absentia” by Geoff Nelder, about a man coming to the realization that he’s a girl’s imaginary friend.

Onto the poetry. The aforementioned Dennis Bagwell is back with four snazzy poems, including the irresistible “Even Serial Killers Need A Vacation” (whose title is self-explanatory). Also returning from volume 1 is the poetry of Joe R. Lansdale, who was in an unexpectedly discordant, free-form mood here, as represented by the accurately monikered “A Strange Poem.” Alec B. Kowalczyk’s work, set mostly in bleak urban environs, is sharp and gritty, while Michael Fletcher’s has a more literate, wordy vibe. I also appreciated “Going Home” by Richard Hill, a variant on W.W. Jacobs’ classic tale “The Monkey’s Paw” told from the point of view of a maggot-ridden walking corpse.

Also from BearManor was IMPOSSIBLY FUNKY: A CASHIERS DU CINEMART COLLECTION, edited by MIKE WHITE. For true film nerds this book is an absolute must, as it is for just about anyone with an interest in Quentin Tarantino, Crispin Glover, Jean-Claude Van Damme, the novels of David Goodis and Charles Willeford, Richard Stark’s Parker books and the LONE WOLF AND CUB films. As one who qualifies on all counts I found IMPOSSIBLY FUNKY a compulsive read.

Also from BearManor was IMPOSSIBLY FUNKY: A CASHIERS DU CINEMART COLLECTION, edited by MIKE WHITE. For true film nerds this book is an absolute must, as it is for just about anyone with an interest in Quentin Tarantino, Crispin Glover, Jean-Claude Van Damme, the novels of David Goodis and Charles Willeford, Richard Stark’s Parker books and the LONE WOLF AND CUB films. As one who qualifies on all counts I found IMPOSSIBLY FUNKY a compulsive read.

In his introduction Film Threat‘s Chris Gore claims that “Mike probably wants to punch me in the face and make me bleed in the most painful way possible,” and I’m certain that’s not far from the truth. Gore turns up in the first article of this collection, “The Tale of the Tape,” about the infamous WHO DO YOU THINK YOU’RE FOOLING video Mike White made highlighting the similarities between RESERVOIR DOGS and Ringo Lam’s CITY ON FIRE. Gore comes off badly in the article, as does THE HANGOVER director Todd Phillips, who as director of the NY Underground Film Festival had a tussle with White over FOOLING. Another entertaining reminiscence turns up in White’s “Theater Daze,” a sharply written piece about working in a Detroit multiplex during the early nineties.

Other chapters contain an appreciation of John Paizs’s obscure gem THE BIG CRIMEWAVE, a scholarly overview of the films of Japanese provocateur Shuji Terayama, a shockingly persuasive appreciation of HIGHLANDER II: THE QUICKENING, much info on Mr. White’s favorite movie BLACK SHAMPOO, and lots more.

Also featured are several interviews, the best of them with filmmakers Guy Maddin and Keith Gordon—who admits “I’ve come to realize that I’m a professional fundraiser, and direct as a hobby.” A brief chat with Bruce Campbell yields an even more memorable line, in answer to the question of whether Campbell has gone Hollywood: “I’m doing an interview for your cheap rag, aren’t I?”

My final BearManor selection is EDISON’S FRANKENSTEIN by FREDERICK C. WIEBEL, JR. It has some irritants  but I treasure it nonetheless, and enthusiastically recommend it to anyone with an interest in the origins and evolution of horror cinema. It tells the story of Thomas Edison’s legendary 1910 adaptation of Mary Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN, possibly the world’s first true horror movie.

but I treasure it nonetheless, and enthusiastically recommend it to anyone with an interest in the origins and evolution of horror cinema. It tells the story of Thomas Edison’s legendary 1910 adaptation of Mary Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN, possibly the world’s first true horror movie.

While many of the details of this production and its reception have been lost to history, Wiebel gathers as much info as he possibly can from vintage advertisements, newspaper clippings, diary entries and so forth. The film’s stars Charles Ogle, Augustus Phillips and Mary Fuller were all fairly prolific silent movie performers who were largely forgotten by the advent of the sound era (with most of their films now lost), and the same can be said for director J. Searle Dawley; Wiebel provides brief but informative overviews of all their careers, as well as that of the once-mighty Edison Manufacturing Co. and the American film industry of the early 1900s. Equally fascinating are Wiebel’s recollections of his dealings with the late Alois Felix Dettlaff, a highly eccentric film collector who for years owned the only existing copy of Edison’s FRANKENSTEIN.

There were some things about this book that bothered me, specifically the author’s frequent bad grammar and misuse of commas. While Wiebel writes in an admirably open and inviting style, if ever a book cried out for a good proofreader it’s this one.

PS PUBLISHING

Another outstanding indie publisher was England’s PS Publishing. Their 2010 horror output commenced with A WEB OF BLACK WIDOWS by SCOTT WILLIAM CARTER, a brisk 97-page collection of six stories centered on longing and desperation.

Another outstanding indie publisher was England’s PS Publishing. Their 2010 horror output commenced with A WEB OF BLACK WIDOWS by SCOTT WILLIAM CARTER, a brisk 97-page collection of six stories centered on longing and desperation.

The title story is a stunner, an altogether unique depiction of madness and (possibly) the supernatural involving some disquietingly lifelike spider tattoos. “The Woman Coughed up By The Sea” is very nearly a sequel, beginning as it does on a woman’s body washing up from the sea—which is how “Web” ended. Here, though, the action is more contained, with an artist finding the body and attempting to use it as inspiration for his paintings. The eerie and poetic “Black Lace and Salt Water” deals with by-now familiar elements, namely the artistic impulse, a pregnant woman and the sea. “She’s Not All There” has a far more impish, dark humored air, being the outrageous account of a young man haunted by his dead wife, who demands he make a spectacle of himself at weddings so she can become whole once again. “Front Row Seats” concerns a desperately lonely man haunted by a spectral starfish that plays essentially the same role as the spider tattoos of the opening story. “Static in A Still House,” like the rest of these stories, pivots on loneliness, in this case that of a broken man who finds he can somehow hear his future. That future turns out pretty bleak, yet the story, like most of its companion pieces, ends on a hopeful note.

ONE FOR THE ROAD is a 1977 story by STEPHEN KING, presented by PS in a graphic novel version illustrated by  JAMES HANNAH. Hannah’s art has a colorful simplicity (even though it doesn’t always match King’s descriptions), particularly in the haunting depictions of a spindly vampire woman emerging spread-armed from a snowy woodland and a creepy red-eyed child staring menacingly up at us.

JAMES HANNAH. Hannah’s art has a colorful simplicity (even though it doesn’t always match King’s descriptions), particularly in the haunting depictions of a spindly vampire woman emerging spread-armed from a snowy woodland and a creepy red-eyed child staring menacingly up at us.

As for “One for the Road” itself, it’s a fine, shivery example of old fashioned horror. The setting is suitably chilly: Maine during an early January blizzard, in which “the snow comes flying so thick and fine that it looks like sand and sounds like that,” while “there’s death in the throat of a snowstorm wind, white death—and maybe something beyond death.”

The time is a quarter past ten. A clueless city man bursts into a remote public house/bar, babbling about leaving his wife and young daughter in a broken-down car in Jerusalem’s lot. Knowing full well the horrific history of the town but feeling charitable, the bar’s owner Tookey and his pal Booth decide to rescue the city man’s wife and child. Reaching the accursed lot, they find the stranded car, but its inhabitants are gone. Spotting a set of footprints, the city man follows them and Tookey and Booth give chase. I won’t reveal any more except to say that our intrepid protagonists succeed in finding the man’s wife and daughter–though maybe it would be better if they didn’t!

CLOWNS AT MIDNIGHT is the premiere novel by Australia’s TERRY DOWLING, a prolific short story scribe and  veteran editor. His intelligence and voluminous knowledge of the genre are fully evident in this highly provocative, intellectually grounded account.

veteran editor. His intelligence and voluminous knowledge of the genre are fully evident in this highly provocative, intellectually grounded account.

The narrator is David Leeton, a Sydney based writer minding the home of some colleagues, located in the rural village Starbreak Fell. David is a coulrophobe, meaning he’s pathologically afraid of all things clown-related. Also afoot are Carlo and Raina Risi, Sardinian pig breeders who own an ancient mask predating the sixteenth century Commedia dell’Arte masks. Carlo’s dissertations on the true origins of the Commedia dell’Arte and (by extension) western religion take up a large portion of the novel, which in keeping with its intellectual bent is part history lesson.

Dowling follows many traditional horror rules in his set-up, in which quite a few bizarre happenings disrupt the protagonist’s existence in Starbreak Fell: strange pictures turn up on David’s personal CD, a mysterious figure is spotted, etc. Other genre standbys include a tentative romance the protagonist enjoys with a local woman, the revelation that one character may have an evil twin, and a WICKER MAN-like climax in which ancient ritual and modern apprehension merge. Of course in these things, as in most everything else, Dowling is always several steps ahead of readers’ expectations.

For a change of pace, PS also put out the MARK MORRIS edited anthology CINEMA FUTURA. It’s a companion-piece to Morris’ 2005 volume CINEMA MACABRE, a collection of essays by a variety of popular authors, each contributing a 2-4 page write-up on a favored horror movie.

For a change of pace, PS also put out the MARK MORRIS edited anthology CINEMA FUTURA. It’s a companion-piece to Morris’ 2005 volume CINEMA MACABRE, a collection of essays by a variety of popular authors, each contributing a 2-4 page write-up on a favored horror movie.

The similarly formatted CINEMA FUTURA’S essays are focused on the cinema of science fiction. Most of the classics of the genre are covered, from METROPOLIS, 2001: A SPACE OSYSSEY, BRAZIL, ROBOCOP, THE MATRIX and AVATAR. James Cameron and Terry Gilliam both receive extremely generous coverage with three films apiece, while Steven Spielberg, shockingly enough, is represented by just one entry, 2002’s MINORITY REPORT. Clearly this is a hip crowd.

True, there’s much you’ll have to forgive, particularly if you, like me, aren’t partial to lengthy personal anecdotes. Joe Lansdale admits his choice of the original INVADERS FROM THE MARS is based on the fact that it scared him as a kid yet “seen as an adult, the first twenty minutes or so of the film still packs a punch, but the latter part of it wavers,” while Guy Adams all-but trashes BLADE RUNNER, a film he loved as a teenager but upon viewing it as an grown-up “spent most of the time cringing.”

Beyond that, Ian R. MacLeod’s piece on A CLOCKWORK ORANGE actually made me view the film, which I’ve seen approximately a thousand times, in an entirely new light. Lucius Shepard’s piece on Jean-Luc Godard’s ALPHAVILLE is among the very few analyses I’ve read of that film that actually comprehends it as the freewheeling goof it is (in contrast to the more academic reviews, which tend to take it far too seriously). Christopher Priest’s observations about Chris Marker’s LA JETEE are equally resonant, and there’s also a perceptive Michael Cobley penned piece on TWELVE MONKEYS, the Terry Gilliam directed remake of Marker’s masterpiece.

Finally from PS: the mind-scraping ESCHER’S LOOPS by Serbia’s ZORAN ZIVKOVIC. ESCHER’S LOOPS is a  series of interconnected narratives grouped into four parts—or loops—that flow into each other in the manner of a literary Möbius strip or, as the title portends, an M.C. Escher painting. Adding to the complexity is the fact that the characters and events of each loop resonate throughout the others; all four loops are self-contained, but to fully comprehend any of them you’ll need to read the entire book.

series of interconnected narratives grouped into four parts—or loops—that flow into each other in the manner of a literary Möbius strip or, as the title portends, an M.C. Escher painting. Adding to the complexity is the fact that the characters and events of each loop resonate throughout the others; all four loops are self-contained, but to fully comprehend any of them you’ll need to read the entire book.

In the first loop we meet nine unnamed people who in nine similarly themed chapters all find themselves preoccupied about something they spied a subsequent character doing, because that character was preoccupied thinking about some other person who was him or herself preoccupied (and so on). Each chapter is structured with geometric precision, with events—a robbery, a man sticking his head in the mouth of a lion, the discovery of a mysterious chest—that recur in the subsequent loops.

The second loop’s main characters are all trapped in some confined space with another individual, who relates a story of someone trapped in a confined space with a person who talks about someone else in a similar predicament. In the third loop a new set of characters all want to commit suicide for various reasons but are interrupted by the appearance of an unidentified old woman—the same old woman each time—who tells a story about someone else who wanted to commit suicide but was interrupted by an old woman. The fourth and final loop is the most complex of the lot, with each chapter containing multiple protagonists. The loop as a whole involves, among various other things, a chest discovered by somebody who always keeps its contents secret and a recitation of a dream that forms each subsequent chapter.

The circular nature of the whole thing means you can start this book at virtually any point and get the same satisfaction as you would with a conventional reading. As for its contents and their chronology, there will likely be as many interpretations as there are readers of ESCHER’S LOOPS.

KURODAHAN PRESS

Speaking of ZORAN ZIVKOVIC, he was well represented by Kurodahan Press, who tend to specialize in English translations of Japanese literature but in 2010 extended their reach to become the second foremost English language publisher of Zivkovic’s work (PS is the first). Kurodahan’s ‘10 Zivkovic publications include:

THE LIBRARY, a collection of six memorably nightmarish stories, all centered on books and their (mostly adverse) affects on various lonely, solitary individuals. The prose is unerringly smooth and spare, and the narratives downright sharp in their unsparing insights into the vagaries of bibliophilia.

THE LIBRARY, a collection of six memorably nightmarish stories, all centered on books and their (mostly adverse) affects on various lonely, solitary individuals. The prose is unerringly smooth and spare, and the narratives downright sharp in their unsparing insights into the vagaries of bibliophilia.

“Virtual Library” explores the impact of the internet on a writer, who discovers a website claiming to have every book ever written available for download—including, to the writer’s great consternation, his own novels. In “Home Library” a man finds a succession of thick books turning up in his mailbox. These books contain all the literature of the world, and come to take up nearly all the space in the hapless protagonist’s apartment. “Night Library” has a man entering a library late at night. He winds up trapped inside the library, which, he learns, has books of people’s lives, including that of the protagonist. “Infernal Library” refers to hell. A “reformed” hell, that is, having been refashioned into a giant library as both punishment (because so few people read) and therapy to the inferno’s denizens. The “Smallest Library” is contained within a single book bequeathed by an eccentric old man. The final story is “Noble Library,” about a snooty man who’s appalled to discover a paperback book in his cherished hardcover collection. This book, it turns out, is the very one under review here.

COMPARTMENTS is a strange and wonderful five story collection packed with enough wisdom and imagination to fill  a sci fi trilogy.

a sci fi trilogy.

The title piece is a novella-length exercise in dreamlike frisson, with a man rushing to board a departing train. A sympathetic conductor helps him aboard, and leads the protagonist into a succession of increasingly odd encounters with several highly eccentric individuals. “The Square” consists of a triple-pronged narrative presented in four chapters; each chapter finds three workaholics undergoing similar experiences that draw them out of their mundane lives and into the town square, where an ecstatic transcendence is in store. A further standout is “The Teashop,” which like “Compartments” involves a fateful train ride. In this case, though, the protagonist, an inquisitive young woman, begins the tale by disembarking from a train. She enters a teashop and, upon ordering a “Tea Made of Stories,” gets quite an earful. Rounding out the collection are “The Telephone,” about a man who receives a series of suspicious phone calls by someone claiming to be Satan, and “First Photograph,” whose narrator attempts to explain a photograph of himself as an infant with his ear intently pressed against his mother’s stomach; apparently he was listening for the heartbeat of his unborn twin brother, who chose to shrink himself down to quantum size rather than be born.

MISS TAMARA, THE READER continues Zivkovic’s love affair with the printed word. It consists of eight stories, each featuring Miss Tamara, a compulsive reader, at a different period of her life. As in THE LIBRARY, the primary subject is books and their various supernatural properties, nearly all of which come to center on one thing: death. Here a new wrinkle is introduced in the form of fruit, which plays a pivotal part in each tale, starting with the titles.

MISS TAMARA, THE READER continues Zivkovic’s love affair with the printed word. It consists of eight stories, each featuring Miss Tamara, a compulsive reader, at a different period of her life. As in THE LIBRARY, the primary subject is books and their various supernatural properties, nearly all of which come to center on one thing: death. Here a new wrinkle is introduced in the form of fruit, which plays a pivotal part in each tale, starting with the titles.

In “Apples” Miss Tamara is eating apples while reading a book and becomes convinced she’s going to die, leading to some decidedly drastic actions. “Lemons” has Miss Tamara taking a strange job: reading aloud to an eccentric young man from a book she learns is the newest work of a reclusive author–which, it transpires, is the author’s way of outwitting death. “Gooseberries” sees Miss Tamara roped into reading a chapter of a book to a blind man in a park, with horrific consequences. “Blackberries” tells of how Miss Tamara’s new reading glasses cause the words in her books to gradually disappear as she reads them. There’s also “Melons,” in which Miss Tamara becomes obsessed with deciding the last book she’ll read before she dies, a query that turns out to be far more pertinent than she knows. The final story is “Fruit Salad,” which ties the previous seven entries together in fitfully cockeyed fashion, with Miss Tamara directed to the “Fruit Salad” café by an anonymous letter, with profoundly odd yet revelatory results…

BAD MOON BOOKS

Unlike 2009, I only read a couple Bad Moon Books publications in 2010 (they no longer send out review copies), but those two books provided more than enough sustenance.

BLOOD & GRISTLE is the first short story collection by MICHAEL LOUIS CALVILLO, showcasing 20 short pieces  distinguished by tightly controlled prose and a brilliantly disturbed imagination.

distinguished by tightly controlled prose and a brilliantly disturbed imagination.

“Head Two” is the starter, a cockeyed look at people with detachable body parts. “The Box” is a deeply bizarre piece that reads like some kind of nutty collaboration between John Hughes and H.R. Giger. “Evolutionary Principles” is one of the book’s standouts, an account of a suicide and the chain reaction of emotions it inspires. “Armor” is even stranger, a free-form reverie concerning poverty, disillusionment and tooth decay. “Consumed” is a vivid depiction of a man trying to worm his way out of a pile of dead bodies that comes to impart some very real queries about life, death and everything in between. The longish “Placebo Effect” is a mind-blower about a college professor looking to balance his two loves: a young woman and crack cocaine. “The Shape of Things to Come” is actually the opening of an as-yet unpublished novel called BASILISK, about a kid who conjures a telepathic dragon through ancient Eastern magic—unwisely, as it turns out! The final piece is nonfiction, revealing why Mr. Calvillo writes what he does. The explanation, as revealed here, has to do with his feelings about death, and the possibility that, contrary to what his Catholic upbringing promised, there may be nothing waiting for us on the other side.

While I didn’t understand everything about these stories, there’s nary a single clunker in the bunch. All the pieces follow their own inscrutable logic to its inevitable (and often quite unpleasant) conclusion.

I also appreciated BLACK AND ORANGE, the impressive debut novel by the talented BENJAMIN KANE ETHRIDGE. It runs 422 pages and doesn’t contain any vampires, zombies or serial killers. What it does have is a richly imagined, wide-ranging mythology with a narrative that can’t be adequately summarized in a single sentence.

I also appreciated BLACK AND ORANGE, the impressive debut novel by the talented BENJAMIN KANE ETHRIDGE. It runs 422 pages and doesn’t contain any vampires, zombies or serial killers. What it does have is a richly imagined, wide-ranging mythology with a narrative that can’t be adequately summarized in a single sentence.

It begins on Halloween night, when members of the Church of Midnight sacrifice a specially endowed person to the Church of Morning, located in a horrific dimension known as the “Old Domain,” in an effort to unite the two. The interdimensional gateway linking the two Churches opens every year on October 31, and it’s this that has apparently given rise to traditional Halloween lore. On this particular Halloween Martin and Teresa, so called “nomads” charged by the shadowy Messenger with protecting the church’s would-be victim, fail in their task.

It seems Martin and Teresa, who spend their lives on the road, won’t have too many more chances at thwarting the Church of Midnight’s plans, as it seems on track to finally achieving a permanent joining of the two churches. The prospective sacrifices are four infant children, to whom Martin and Teresa are guided by the Messenger.

There is of course much, much more to this novel, including Chaplain Cloth, a horrific manifestation of a united Midnight and Morning Church; an unforgettable hallucinatory journey Martin experiences after ingesting a shroom at the instruction of the Messenger; and the godlike Messenger himself, who reports to us in brief first person chapters. There are also episodes of breakneck action, wild sex, lively dialogue and an unusually strong and resonant conclusion.

ZOMBIES

I’m officially sick of zombies, and generally try to avoid zombie themed fiction. These days, however, that’s pretty much impossible, as over the past year I wound up reading four major books (four more than intended) centered on the living dead, and a fifth that comes close.

THE NEW DEAD is an anthology edited By CHRISTOPHER GOLDEN (St. Martin’s Griffin). The stories, by talents  like Max Brooks, Joe Hill and Joe R. Lansdale, are solid for the most part, but I didn’t find the book overall to be anything special.

like Max Brooks, Joe Hill and Joe R. Lansdale, are solid for the most part, but I didn’t find the book overall to be anything special.

The opening story is “Lazarus” by John Connolly, a dour look at the world’s first zombie, brought back to life by Jesus Christ. It’s followed by the more interesting “What Maisie Knew” by David Liss, about people who get off on raping and murdering zombies. The standout entry, I feel, is “Family Business” by Jonathan Maberry, which achieves its effects via unpretentious storytelling skill.

Of the star contributors, Max Brooks’ “Closure, Limited” is essentially a lost chapter of his epic WORLD WAR Z (and will likely be incomprehensible to anyone who hasn’t read that book). “In the Dust” by Tim Lebbon centers on a plague much like those of THE CRAZIES or 28 DAYS LATER, but unlike them is resolutely quiet and subdued in tone. Rick Hautala’s “Ghost Trap” is effective largely because of its containment—it’s about just one zombie, a creepy man chained up in the ocean. Joe R. Lansdale’s “Shooting Pool” is likewise noteworthy for its tightness. The setting is a pool hall wracked by a killing—or, more accurately, a re-killing. Joe Hill contributes “Twittering from the Circus of the Dead,” composed entirely of tweets from a girl who accompanies her family to a zombie circus. Hill is largely successful at conveying intrigue and suspense through his audacious formatting, although I’m unsure the story would have worked all that differently without the stylistic overlay.

SHAKESPEARE UNDEAD by LORI HANDELAND was also published by St. Martin’s Griffin. It’s a goofy faux-historical novel detailing William Shakespeare’s career as a centuries-old vampire. This concept helps explain the incredible breadth of Shakespeare’s output. Also explained herein is the identity of the Bard’s so-called “Dark Lady”: a zombie hunting babe named Katherine.

SHAKESPEARE UNDEAD by LORI HANDELAND was also published by St. Martin’s Griffin. It’s a goofy faux-historical novel detailing William Shakespeare’s career as a centuries-old vampire. This concept helps explain the incredible breadth of Shakespeare’s output. Also explained herein is the identity of the Bard’s so-called “Dark Lady”: a zombie hunting babe named Katherine.

It’s not only vampires that are loose in this novel’s late-1500s London, as flesh eating zombies also litter the land. Most people mistake the living dead for plague victims, but Kate and Shakespeare know the truth. These two initiate a passionate romance, with Kate unaware of her lover’s true nature. There’s also the problem of the individual who caused the zombies to rise, who is very much at large, and hostile to our heroes.

There’s nothing too deep here, but the novel accomplishes its purpose: it’s lively and funny, and a fast, easy read overall. Author Lori Handeland is clearly well versed in Shakespeare’s work and provides clever nods to HAMLET, THE TEMPEST and, most prominently, ROMEO AND JULIET, whose conclusion is directly aped in Handeland’s perversely upbeat ending.

HANDLING THE UNDEAD (Thomas Dunne Books) was by JOHN AJVIDE LINDQVIST, the Sweden-based author  of LET THE RIGHT ONE IN. It’d be easy to say that HANDLING THE UNDEAD does for zombies what the former novel/film did for vampires, but this new book is a far more idiosyncratic work overall.

of LET THE RIGHT ONE IN. It’d be easy to say that HANDLING THE UNDEAD does for zombies what the former novel/film did for vampires, but this new book is a far more idiosyncratic work overall.

The setting is Stockholm during a sweltering heat wave, where some unexplained supernatural occurrence causes the electrical appliances to go haywire. For the mild-mannered protagonist David this also marks the unexpected death of his wife in a car accident. Yet upon reaching the hospital to identify the body something even stranger occurs: David’s deceased wife unexpectedly returns to life.

Other characters caught in the melee are Gustav, a writer attempting to adjust to the death of his young son, and Flora, a psychic woman whose grandmother has passed. Luckily these deaths have occurred recently, as only people who’ve been dead two months or less come back—which is indeed what occurs in both cases, with all manner of darkly comedic complications. Swedish authorities eventually take the drastic step of quarantining the zombies, which throws the lives of everyone into turmoil, and leads to an intense George Romero-esque climax.

Outside that climax there’s little in the way of the type of flesh eating insanity of most zombie thrillers. Lindqvist’s interest is in how his characters deal with death, certainly a concept with universal significance. That doesn’t mean the novel isn’t idiosyncratic in the extreme, alternating straightforward storytelling with interviews and chronological recountings of the zombie outbreak. HANDLING THE UNDEAD may not quite be a classic of the zombie genre, but it’s definitely a unique standout.

Far less inspiring was AUTUMN by DAVID MOODY (yet another dispatch from St. Martin’s Griffin). It fully evinces the strong, unpretentious prose of more potent Moody efforts like HATER, and also the headlong narrative drive. But unlike HATER, AUTUMN never succeeds in distinguishing itself from the countless other media that share its frankly hackneyed concept.

Far less inspiring was AUTUMN by DAVID MOODY (yet another dispatch from St. Martin’s Griffin). It fully evinces the strong, unpretentious prose of more potent Moody efforts like HATER, and also the headlong narrative drive. But unlike HATER, AUTUMN never succeeds in distinguishing itself from the countless other media that share its frankly hackneyed concept.

The setting is England in the wake of a contagion that kills 99 percent of the population. Moody wastes no time getting to the action, with maintenance man Carl, computer worker Michael and teacher Emma joining up with a small band of survivors at a community center. Before any of them can get a handle on what’s happening the dead begin rising—and anyone even slightly familiar with zombie lore knows that the undead are after just one thing: human flesh!

To his credit, Moody doesn’t waste a lot of time on the expected love triangle (the protagonists’ main concern is survival, which leaves little time for romance). That’s not to say, unfortunately, that the proceedings are in any way difficult to predict. In Moody’s defense, this novel was initially published (on the internet) several years ago, when the zombie apocalypse tale probably didn’t seem as tired as it does now. That, however, doesn’t change the fact that AUTUMN is essentially SHAUN OF THE DEAD without the comedy—or the imagination.

While on the subject of David Moody novels, his DOG BLOOD, the long-awaited follow-up to HATER, appeared  in 2010 (from Thomas Dunne Books). It functions primarily as a bridge between the first and last parts of a projected trilogy, and so isn’t entirely satisfying as a stand-alone story.

in 2010 (from Thomas Dunne Books). It functions primarily as a bridge between the first and last parts of a projected trilogy, and so isn’t entirely satisfying as a stand-alone story.

DOG BLOOD picks up where HATER left off, with society in ruins and existence reduced to a perpetual war. Former government employee Danny McCoyne is adjusting to life as a “Hater”—that is to say, a beast-like (and not a little zombie-ish) individual driven by raw aggression to brutalize and kill anyone who isn’t like him. As a Hater Danny finds himself focused completely on the “unchanged,” his eternal enemies who must apparently be snuffed out at all costs.

One of DOG BLOOD’S great virtues, which it shares with its predecessor, is its constant unpredictability. When early on in the book Danny is captured and imprisoned by a band of apparent Unchanged seeking to cure him, it seems the narrative arc is set…but of course it isn’t!

There’s a great deal of wit and cleverness to this novel. Note the chapter headings, with those told from Danny’s Hater-addled POV denoted with numbers and others by roman numerals. The novel is also quite topical, and distressingly so, in its troubling look at a world torn apart by warring factions, with the only options being to submit to hate and aggression or fight against those who already have.

BRENDAN CONNELL

The brilliant BRENDAN CONNELL was one of several notable discoveries I made in 2010. His fiction is uniquely erudite and idiosyncratic, but also quite wide-ranging in style and tone. Quite simply, there’s no one else quite like him.

METROPHILIAS (Better Non Sequitur), Connell’s first 2010 collection, is a subtly deranged, obliquely beautiful oddity. Its stories span the globe and the centuries, with each set in and named after a different city. The contents are extremely minimal in tone and style (few last more than two or three pages) yet all have a lasting poetic resonance. Nearly every perversion you can think of, from bald head and high heel fetishism to necrophilia to statue prostitution(!), is explored herein, as well as none-too-pleasant subjects like self mutilation and pyromania, yet the overriding tone is one of wistful romanticism.

METROPHILIAS (Better Non Sequitur), Connell’s first 2010 collection, is a subtly deranged, obliquely beautiful oddity. Its stories span the globe and the centuries, with each set in and named after a different city. The contents are extremely minimal in tone and style (few last more than two or three pages) yet all have a lasting poetic resonance. Nearly every perversion you can think of, from bald head and high heel fetishism to necrophilia to statue prostitution(!), is explored herein, as well as none-too-pleasant subjects like self mutilation and pyromania, yet the overriding tone is one of wistful romanticism.

Particularly representative entries include “Kiev,” the twisted tale a man in love with a woman’s severed head; “Edinburgh,” concerning a civil servant driven to suicide by his all-consuming infatuation with the letter W; “Peking,” wherein a prince grows obsessed with a ceramic vase that becomes his undoing; “Seville,” whose protagonist is a swordsman who finds bliss by running himself through with his beloved sword; and “Thebes,” about an ancient Egyptian king whose ideal mate is a woman whose nose is “enormous, bulbous, deliciously ampliform, so large indeed that it hid the rest of her face…”

UNPLEASANT TALES, from Eibonvale Press, is an even stronger sampling of Connell’s talents. The lengthy  “Maker of Fine Instruments” is an astonishing account of a music student falling under the spell of a master musician who makes instruments out of living things. “The Black Tiger” is set in the Roman province of Numidia, where a seductive woman single-handedly takes on a ravenous beast. “The Putrimaniac” reveals an all-embracing infatuation with the grotesque in its portrayal of a connoisseur of rot and decay.

“Maker of Fine Instruments” is an astonishing account of a music student falling under the spell of a master musician who makes instruments out of living things. “The Black Tiger” is set in the Roman province of Numidia, where a seductive woman single-handedly takes on a ravenous beast. “The Putrimaniac” reveals an all-embracing infatuation with the grotesque in its portrayal of a connoisseur of rot and decay.

Particularly transgressive tales include “A Dish of Spouse,” containing one of most arresting opening lines I’ve yet encountered (“After Mrs. Shapiro had eaten Maurice, her husband, she felt a sense of regret”) and “The Cruelties of Him,” about a learned but thoroughly amoral doctor and the depraved experiments he performs on a young boy and his own wife.

For sheer weirdness the standout is “Wiggles,” a tiny tale of madness and mutilation related in fractured, sensory-inflected prose. Also noteworthy is “Mesh of Veins,” an outrageous account of body modification that concludes with the protagonist looking at his insanely modified body in a mirror—and finding he knows “the meaning of true fear.”

The final story is “We Sleep on A Thousand Waves Beneath the Sea,” centering on pirates and a female sea monster they acquire, with much indiscriminate slaughter adding to the aura of a tale, and overall book, of elegant and profound grotesquerie.

NONFICTION

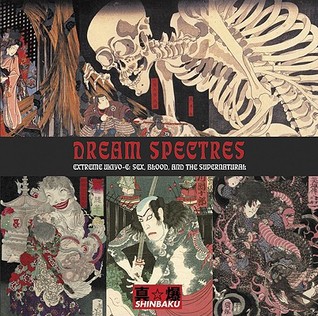

DREAM SPECTRES: EXTREME UKIYO-E by JACK HUNTER (Creation) is a lively study of ukiyo-e (“images from the floating world”) woodblock printed art from 18th and 19th Century Japan. Ukiyo-e was an evident forerunner of today’s manga as well as quite a few popular J-Horror motifs, notably the pasty-woman-with-black-hair of RINGU and THE GRUDGE, which apparently had its inception in a 1750 ukiyo-e painting by Maruyama Okyo. Graphic depictions of rape, bondage, torture and dismemberment were all common elements of this mass produced art form, which was viewed by Japanese citizens of every social strata.

DREAM SPECTRES: EXTREME UKIYO-E by JACK HUNTER (Creation) is a lively study of ukiyo-e (“images from the floating world”) woodblock printed art from 18th and 19th Century Japan. Ukiyo-e was an evident forerunner of today’s manga as well as quite a few popular J-Horror motifs, notably the pasty-woman-with-black-hair of RINGU and THE GRUDGE, which apparently had its inception in a 1750 ukiyo-e painting by Maruyama Okyo. Graphic depictions of rape, bondage, torture and dismemberment were all common elements of this mass produced art form, which was viewed by Japanese citizens of every social strata.

DREAM SPECTRES’ true selling points are of course the hundreds of full color reproductions of ukiyo-e paintings. The grossness and outrage of the pornographic illustrations on display here, nearly all featuring absurdly oversized genital organs, are undeniably striking. So too the spirited bloodletting of Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, who specialized in depictions of reality-based carnage (including a man ripping another’s face from his skull), and the near-psychedelic palettes of Kuniteru Utagawa and Shuntei Katsukawa, who pictured brave warriors battling dragons and giant sea turtles.

At the other end of the spectrum are poetic depictions of supernatural calamity by the likes of Kyosai Kawanabe, whose rendering of a madman dancing on a giant skull is a most novel sight, and Kuniyoshi Utagawa, who gives us a profoundly haunting image of a ship besieged by dimly-glimpsed ghosts. Finally there are the haunting and ethereal paintings of the abovementioned Maruyama Okyo, who was apparently inspired to create his famous portrait of a ghostly woman after encountering the spirit of his deceased mistress in a dream.

For anyone with even a passing interest in the 1973 English horror classic THE WICKER MAN, INSIDE THE  WICKER MAN: HOW NOT TO MAKE A CULT CLASSIC by ALLAN BROWN (Polygon) is required reading, being an unusually erudite and well written account of the film’s making and reception.

WICKER MAN: HOW NOT TO MAKE A CULT CLASSIC by ALLAN BROWN (Polygon) is required reading, being an unusually erudite and well written account of the film’s making and reception.

As the subtitle makes clear, this book allegedly concerns itself with how “not” to make a cult classic, with THE WICKER MAN’S location shoot apparently “one of the most notorious black comedies in cinema history.” Really? Because as one who’s worked on his share of low budget movie sets, I can attest that there wasn’t much here that seemed outside the norm for such fare, from the painfully low budget to the clash of egos between writer-producer Anthony Shaffer and director Robin Hardy to the film’s butchering at the hands of clueless studio execs.

Brown, in any event, proves himself a good guide through THE WICKER MAN’S conception, production, reception and resurrection. He also includes extensive descriptions of the film’s copious lost footage, as well as info on Shaffer’s planned sequel and the dreadful 2006 Hollyweird remake.

Brown is quite an opinionated scribe, and not above offering pithy descriptions of his subjects (co-star Christopher Lee comes off as a first-class blowhard throughout). Brown is certainly entitled to his views, but for those of you who don’t care about THE WICKER MAN one way or the other, I strongly doubt his opinions on the film will do much to influence yours.

PSYCHOMAGIC: THE TRANSFORMATIVE POWER OF SHAMANIC PSYCHOTHERAPY (Inner Traditions) is by the incomparable ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY, who expands on his self-created technique of “Psychotherapy,” wherein he uses surreal, dream-based principles in curing people of their various neuroses. Of course, as Jodorowsky readily acknowledges, this is something only he can accomplish, having been schooled in the techniques of a Mexican sorceress who used many of the same elements to cure peoples’ ills.

PSYCHOMAGIC: THE TRANSFORMATIVE POWER OF SHAMANIC PSYCHOTHERAPY (Inner Traditions) is by the incomparable ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY, who expands on his self-created technique of “Psychotherapy,” wherein he uses surreal, dream-based principles in curing people of their various neuroses. Of course, as Jodorowsky readily acknowledges, this is something only he can accomplish, having been schooled in the techniques of a Mexican sorceress who used many of the same elements to cure peoples’ ills.

Comprised largely of a series of interviews with Jodorowsky by an appropriately skeptical disciple, the book is rich, confounding and, as with anything related to Jodorowsky, completely bizarre. Psychomagic therapy involves Jodorowsky listening to peoples’ family histories and then having them do things. Things like humping the dirt of a man’s estranged mother’s grave…or burning a manuscript as a cure for writers’ block…or pissing into an absorbent surface to get in touch with one’s inner child. You get the idea.

This book often reads like a debauched variant on THE SECRET, with Jodorowsky’s proscription of the powers of positive thinking to change reality, and at other times like the weirdest Carlos Castaneda book ever (at one point Jodorowsky actually details a meeting he had with Mr. Castaneda). There’s also a transcription of the events of the infamous late sixties “Panic” happening put on in Paris by Jodorowsky and his fellow provocateurs that concluded with Jodorowsky disappearing into a giant vagina. Clearly this guy is equal parts genius and madman, and this book comes highly recommended whether you agree with Jodorowsky’s views or not.

ASSORTED ODDITIES

The DES LEWIS edited NULL IMMORTALIS, from Megazanthus, is the final installment of the weird and wonderful  Nemonymous anthology series. In NULL IMMORTALIS two things are constant: the enigmatic term “Null Immortalis” and the name Tullis—after Scott Tullis, who won a competition to appear in every story.

Nemonymous anthology series. In NULL IMMORTALIS two things are constant: the enigmatic term “Null Immortalis” and the name Tullis—after Scott Tullis, who won a competition to appear in every story.

The stories have a considerable range of subject matter, including a man’s remembrance of his shrinking father (Daniel Pearlman’s “A Giant in the House”), a possibly imaginary neck growth (Tim Casson’s “The Scream”) and a wicked satire of the publishing industry in the form of an eccentric ghost story (Joel Lane’s “The Drowned Market”). Dreams are a popular topic: “Even the Mirror” by Ursula Pflug is about a love affair conducted entirely in dreams, and the novella-length “The Shell” by Tony Lovell concerns a series of extremely vivid dreams that come to overtake a man’s reality during a vacation.

David M. Fitzpatrick’s “Lucien’s Menagerie” is one of the more straightforward offerings, an old-fashioned horror story about a woman who agrees to stay overnight in the mansion belonging to her deceased ex-husband, a taxidermist, as a condition of his will…with 52 animal statues and her husband’s own stuffed corpse! Stephen Bacon’s wistful “The Toymaker of Breman” is another (mostly) straightforward offering, about a boy who, following an apparent car accident, finds himself in the cozy but rather creepy home of a German toymaker. “The Green Dog” presents a surreal meditation on identity (or lack thereof) by the brilliant Steve Resnic Tem, about a man at the end of his life who’s also a green dog. “Supermarine” by Tim Nichols closes the volume out in fittingly unfitting fashion with a supremely odd tribute to the fiction of J.G. Ballard. Truthfully, I can’t tell you precisely what this story is about, but it is rich and fascinating, involving a troubled actress, an Easter egg hunt and a cormorant invasion amid a lot of very Ballardian landscapes.

One of my favorite literary discoveries of 2010 was the outrageous SYLVOW by DOUGLAS THOMPSON (Eibonvale), which unfolds as, essentially, a sustained hallucination.

One of my favorite literary discoveries of 2010 was the outrageous SYLVOW by DOUGLAS THOMPSON (Eibonvale), which unfolds as, essentially, a sustained hallucination.

The focus is on the (imaginary) British city Sylvow, located at the point where the Roman Empire began its decline, apparently due to the area’s impenetrable forests. It seems that nature has finally decided to finish the job it began so long ago, conclusively ridding the Earth of human beings in a wildly surreal succession of catastrophes. Among other things, a tiny beating heart is found in a split-open peach and a blue eye in the center of an orange, and before long Sylvow is overrun by unidentified vegetation, giant insects and odd vegetables that drop from the sky and fasten themselves to the ground.

Tonally this novel is all over the place, with thoughtful environmental screeds juxtaposed with episodes of scientifically questionable surrealism and a fair amount of bawdy humor (as when the greenery invading a woman’s home entwines itself into a giant penis that she, being sex-deprived, utilizes accordingly). You can be forgiven for interpreting SYLVOW as a parody of an eco-thriller, or just a rich and bizarre literary mutation that deserves to perplex and delight the widest possible audience it can attain.

OLD ORDER by JONATHAN JANZ (Untreed Reads) is only 31 pages long yet packs a considerable punch. Its  depiction of a sweltering rural environ is consistently vivid and atmospheric, with characters who feel entirely convincing and a narrative that doesn’t announce itself as horror-related until the mind-roasting climax.

depiction of a sweltering rural environ is consistently vivid and atmospheric, with characters who feel entirely convincing and a narrative that doesn’t announce itself as horror-related until the mind-roasting climax.

Horace Yoder is an antique shop owner who passes himself off as Amish in order to con his way into the home of the McCarrick family. No less than four generations of this clan are afoot in the McCarrick household, including Grandma Shirley and her ancient mother Agnes, the hot-to-trot Belinda and her equally lascivious daughter Susan. Horace himself harbors some unsavory secrets involving his father, who as punishment for a petty theft slashed Horace with a knife years earlier and left a thick scar on his back, a “constant reminder to do his stealing far from home, far enough so the merchandise could never be traced back to him.” Thus, Horace stocks his antique shop with items filched from far-off places…like the McCarricks’ farmhouse.

Horace enters the place on the pretext of doing odd jobs for the family, and is quickly seduced by both Belinda and Susan. After cleaning out Agnes’ jewelry box, Horace attempts an escape…and what happens next I’ll leave for you to discover on your own.

PEOPLE LIVE STILL IN CASHTOWN CORNERS by TONY BURGESS (ChiZine Publications) is a twisted yet highly literary tale of mass murder told from the killer’s point of view. That killer is Bob Clark, the troubled owner of a gas station in a tiny Ontario town known as Cashtown Corners. One day Bob snaps, and, for reasons he himself doesn’t entirely comprehend, kills a woman in her car. He follows this with another equally senseless murder and then a cop killing, which turns him into an immediate fugitive. Bob winds up in a house whose occupants he murders—and then goes completely bonkers, hallucinating lengthy conversations with his victims’ corpses and relentlessly pondering the minutiae of his actions, with no ready answers available.

PEOPLE LIVE STILL IN CASHTOWN CORNERS by TONY BURGESS (ChiZine Publications) is a twisted yet highly literary tale of mass murder told from the killer’s point of view. That killer is Bob Clark, the troubled owner of a gas station in a tiny Ontario town known as Cashtown Corners. One day Bob snaps, and, for reasons he himself doesn’t entirely comprehend, kills a woman in her car. He follows this with another equally senseless murder and then a cop killing, which turns him into an immediate fugitive. Bob winds up in a house whose occupants he murders—and then goes completely bonkers, hallucinating lengthy conversations with his victims’ corpses and relentlessly pondering the minutiae of his actions, with no ready answers available.

This novel is somewhat lacking in narrative clarity (why don’t the police ever search the house where Bob holes up?), with elegantly scatterbrained prose and a disarmingly carefree, vaguely sarcastic tone. This makes it difficult to discern whether the novel’s eccentricities are intended as genuine depictions of the narrator’s deteriorating psyche or simply mere authorial quirks.

Adding to the weirdness are a section of black-and-white photographs, allegedly of the crimes and locales depicted in the novel. Also pictured is a World Trade Center birdhouse sculpture made by one of Bob’s victims that ties in with a reverie Bob has early on involving the events of 9-11. What precisely this juxtaposition might signify (if anything) is, like so much else in these pages, left up to the reader to decide for him/herself.

Speaking of weirdness, novels don’t come much weirder than SLAUGHTERHOUSE HIGH by ROBERT  DEVEREAUX (Deadite Press), which I previously reviewed under its original title DEADOLESCENCE.

DEVEREAUX (Deadite Press), which I previously reviewed under its original title DEADOLESCENCE.

The setting is the Demented States of America, led by one President Windfucker. Surgically implanted vaginal teeth are prevalent in this society, as are three-way marriages and school courses in butchery.

The school in this case is Corundum High in Kansas. It’s prom night, and here, as in every high school across the DSA, a yearly ritual is about to commence: the school will be closed off and a boy and girl selected to be butchered at the hands of a “designated slasher.” Afterward the corpses are laid out for the rest of the students to rip apart, each taking away a piece of their dead friends as a nostalgic keepsake. This year, however, things are different: once the killing commences, it’s clear that the slasher isn’t stopping at just one couple—and that there’s more than one slasher!

You can Call Robert Devereaux many things, but predictable isn’t one of them. The early chapters read like an amalgam of A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and a Zucker Brothers parody that gives way to all-out splatter in the latter ones. The novel’s an enigma: it could be overwrought trash, but then again it might just contain the key to decoding the secrets of the universe.

Finally we have HELLFIRE & DAMNATION by CONNIE CONCORAN WILSON (Sam’s Dot Press), an anthology that is genuinely, blazingly original. The book is rigorously structured around the nine circles of Hell as laid out in Dante’s INFERNO, yet the contents couldn’t be more varied in subject matter. What unites them is the unerringly rational, straightforward prose, which is unlike anything else in horror fiction.

Finally we have HELLFIRE & DAMNATION by CONNIE CONCORAN WILSON (Sam’s Dot Press), an anthology that is genuinely, blazingly original. The book is rigorously structured around the nine circles of Hell as laid out in Dante’s INFERNO, yet the contents couldn’t be more varied in subject matter. What unites them is the unerringly rational, straightforward prose, which is unlike anything else in horror fiction.

Among the standout tales are “Hotter Than Hell,” inspired by the final words of real death row inmates; “Konerak” a wild tale of Oriental sorcery taken from the real-life incident of the man who almost escaped the clutches of the late Jeffrey Dahmer; the quietly unnerving “Hell to Pay,” which combines a look into Amish life with an intriguing speculation on the origins of schizophrenia and multiple sclerosis; “On Eagles’ Wings,” concerning a weird cultist, a young girl and an unhealthy obsession with birds; and “An American Girl,” concerning the fact-based murder of a teenage girl in snowy Illinois, with the bulk of the tale taken up with a methodical depiction of the pubescent killers’ attempts at disposing of the corpse.

You won’t find another collection like this one. Some readers, I’m sure, will be put off by the book’s oddness, yet it fulfills most every expectation one might have for a horror anthology, being readable, entertaining and deeply unsettling in a manner unique to itself.

REPRINTINGS

Among the notable past novels reprinted in 2010 was MATTHEW STOKOE’S sicko classic COWS, courtesy of  Akashic Books. It’s the extremely visceral account of Steven, a young man living with his hateful mother whom he affectionately dubs the “Hagbeast.” Steven takes a job in a slaughterhouse whose employees like to cut holes in freshly slaughtered cow carcasses and stick their dicks in ‘em. Such work inspires Steven to do away with the Hagbeast by feeding her a steady diet of shit…when he’s not cavorting with his girlfriend, a young woman obsessed with flushing out the toxins in her system to the point of sticking a probe up her ass with a camera on the end of it while Steven fucks her.

Akashic Books. It’s the extremely visceral account of Steven, a young man living with his hateful mother whom he affectionately dubs the “Hagbeast.” Steven takes a job in a slaughterhouse whose employees like to cut holes in freshly slaughtered cow carcasses and stick their dicks in ‘em. Such work inspires Steven to do away with the Hagbeast by feeding her a steady diet of shit…when he’s not cavorting with his girlfriend, a young woman obsessed with flushing out the toxins in her system to the point of sticking a probe up her ass with a camera on the end of it while Steven fucks her.

There’s also a talking pig who gets unexpectedly chummy with our none-too-stable hero, exhorting him to lead a revolution against the humans, and so taking the story in an entirely new, fantastical direction. COWS was its author’s first novel, and so is far from perfect (Stokoe’s follow-up HIGH LIFE is stronger), but it’s quite vivid and extremely readable, showcasing a totally unique imagination.

Underland Press’ new edition of THE COMPLETE DRIVE-IN by JOE R. LANSDALE is another must, as it contains Lansdale’s essential 1988 novella THE DRIVE-IN, as well as 1989’s THE DRIVE-IN 2 (which I didn’t much care for) and 2005’s DRIVE-IN 3 (which I haven’t read).

Underland Press’ new edition of THE COMPLETE DRIVE-IN by JOE R. LANSDALE is another must, as it contains Lansdale’s essential 1988 novella THE DRIVE-IN, as well as 1989’s THE DRIVE-IN 2 (which I didn’t much care for) and 2005’s DRIVE-IN 3 (which I haven’t read).

THE DRIVE-IN is quite simply one of the most outrageous novels of all time. It tells what happens when the patrons of a six screen Texas drive-in called The Orbit are taken hostage by aliens apparently bent on making a low budget movie much like the ones playing on the Orbit’s screens.

The Orbit is closed off from the rest of the world, leaving its redneck patrons to subside on soda, candy, popcorn and a non-stop marathon of cheesy horror flicks. Eventually the aliens decide to shake things up by turning two of the arena’s more inhospitable patrons into a monstrous entity called the Popcorn King. The PC fancies himself a god, and takes to vomiting popcorn with bloodshot eyeballs in each kernel that when imbibed make people fall under the PC’s spell. Of course, this does nothing to stem the inevitable fights, stabbings, cannibalism and crucifixions.

The book contains a goodly amount of grue, bad language and endlessly quotable one-liners. The feverish imagination on display is impressive, as is Lansdale’s spot-on portrayal of Texas white trash culture. But for all its jokey high spiritedness, the book has a dark side: the author claims it was written during a particularly rough time in his life, and the meanness shows through, giving this outrageous account more gravity than you might expect.

JOYRIDE is a nineties-era JACK KETCHUM novel that was republished in mass market form by Leisure Books shortly before they went kablooey (and so is already out of print). Look up the word “relentless” in the dictionary and you’ll find a reference to this novel…or at least, you should.

shortly before they went kablooey (and so is already out of print). Look up the word “relentless” in the dictionary and you’ll find a reference to this novel…or at least, you should.

It’s about an abused woman who together with her lover murders her abusive hubbie. The crime seems to go off without a hitch, but there was a witness they don’t know about—who just happens to be a murderous psychopath! The nutcase tracks the murderers down and enlists ‘em in an all-out killing spree, during which a number of innocent people are killed on and off a major highway. The three protagonists end up back in the psycho’s own neighborhood, where the slaughter reaches unimaginable heights.

Like I said, this is utterly relentless stuff that NEVER flinches or compromises its grim worldview. The writing is spare, compact and near insanely precise, with a powerfully streamlined narrative that never loses its footing. So assured is Ketchum’s prose that even the frequent flashbacks (usually an annoyance) never compromise the forward momentum. A one-sitting read for sure!

There was also, for those of you with deep pockets, an ultra-expensive hardcover reprinting (the first in over 40 years) of E.H. VISIAK’S 1929 classic MEDUSA by Centipede Press. Many rank it among the greatest horror novels of the century; I’m not exactly in agreement with that sentiment, but do concur that it’s a one-of-a-kind accomplishment.

There was also, for those of you with deep pockets, an ultra-expensive hardcover reprinting (the first in over 40 years) of E.H. VISIAK’S 1929 classic MEDUSA by Centipede Press. Many rank it among the greatest horror novels of the century; I’m not exactly in agreement with that sentiment, but do concur that it’s a one-of-a-kind accomplishment.

It’s written in a self-consciously “classical” prose style that can be off-putting at first, but reads just fine once one adjusts. Like a warped combination of TREASURE ISLAND, PARADISE LOST (no surprise: the author was an authority on Milton) and H.P. Lovecraft’s entire oeuvre, it’s the story of a kid hitting the high seas sometime in the seventeenth century with a band of pirates.

These would-be swashbucklers happen upon a mysterious ship, deserted but for a single babbling madman. Even worse, it turns out that one of the pirates has been keeping a large fishlike monster in his hull. From there things get reeeally strange, as our heroes find themselves deluged by a gaggle of the monster’s kin, who drag everyone back to their sunken layer to confront the Medusa, a giant tentacled critter who transfixes the men and drains their souls. Only the spiritually inclined survive the assault, including the protagonist (of course!) and a Bible-thumping ship’s mate, who is halted by the hand of God Himself!

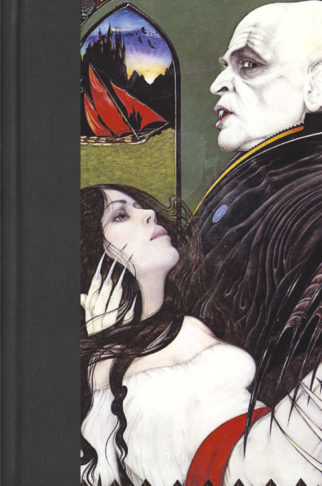

Another worthy (and highly expensive) Centipede Press 2010 re-release was the late PAUL MONETTE’S  novelization of Werner Herzog’s NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE. Monette establishes his own ground in a deeply felt, poetic and sensuous piece of work that nearly works as a stand alone novel. Not quite, though: it’s clunky, as most movie novelizations tend to be, grouped into lengthy paragraphs that tend to repel rather than compel attention. The time frame Monette had to write the book was by his own admission “insane,” and he clearly missed out on a lot of much-needed revision time.

novelization of Werner Herzog’s NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE. Monette establishes his own ground in a deeply felt, poetic and sensuous piece of work that nearly works as a stand alone novel. Not quite, though: it’s clunky, as most movie novelizations tend to be, grouped into lengthy paragraphs that tend to repel rather than compel attention. The time frame Monette had to write the book was by his own admission “insane,” and he clearly missed out on a lot of much-needed revision time.

Still, what Monette managed to achieve with this slender book is impressive. Herzog’s film was, despite its visual brilliance, a rather thin one, in keeping with its spare silent movie source material. Monette has filled in the back story Herzog left out and bulked up the characters in the process, and done so in satisfying and convincing fashion. Of course you already know the story, if not from the movies than from DRACULA (which NOSFERATU plagiarized), but here, as in all other aspects of this book, Monette lends a uniquely provocative, hallucinatory touch that puts his work over the top.

Other 2010 reprints of interest include new editions of THE BRIDGE by JOHN SKIPP & CRAIG SPECTOR (Leisure), THE NINTH CONFIGURATION by WILLIAM PETER BLATTY (Centipede Press), THE FOG by JAMES HERBERT (Centipede again) FRIDAY NIGHT IN BEAST HOUSE by RICHARD LAYMON (Leisure), THE SHADOW ON THE HOUSE by MARK HANSOM (Ramble House), SUB ROSA: STRANGE STORIES by ROBERT AICKMAN (Tartarus Press) and HANNS HEINZ EWERS’ ALRAUNE, which Side Real Press promises is a “new, fully restored” translation, with text not included in the original John Day publication from which I culled my review of a few years ago.

LOOKING FORWARD…

Particularly promising upcoming titles for 2011 include: THE WOMAN by JACK KETCHUM and LUCKY MCKEE (DP), WILLY by ROBERT DUNBAR (Uninvited Books), WILD by LINCOLN CRISLER (Damnation Books), THE KENSEI by JON F. MERZ (St. Martin’s Press), BLEED FOR YOU by MICHAEL LOUIS CALVILLO (Damnation Books) and CHRISTMAS WITH THE DEAD by JOE LANSDALE (PS Publishing). All look good, as I can personally testify, having already got a hold of several of those books in pre-release form. 2011 looks like it’ll be a strong year for horror fiction, even though it will likely take a bit of digging to get at the goodies.

Bring it on!