Welcome to the first installment of my year-end overview of the year in horror fiction. I haven’t been able to read every genre publication of ’06, in fact haven’t even gotten close, meaning that, regrettably, the following won’t be nearly as inclusive as my annual year-end movie pieces. I’m hoping, though, that it will serve to point out some worthwhile books you might have passed up while at the same time providing a fresh perspective on better-known bestseller fare.

I’ll refrain from offering blanket categorizations of 2006’s literary output. I don’t know that the year was a banner one for horror fiction, but I certainly don’t think it was all that bad. There was some good books, some bad, some so-so, and a few I’d call great, which I believe makes for a pretty solid year.

First, here’s my nominee for BOOK OF THE YEAR. It’s not a horror novel, but rather a nonfiction anthology about horror novels: HORROR: ANOTHER 100 BEST BOOKS, edited by STEPHEN JONES & KIM NEWMAN (Carroll & Graf). It follows Jones & Newman’s seminal 1988 collection HORROR: 100 BEST BOOKS, which has long been a quintessential volume in my library, containing eradiate essays by leading horror writers—Stephen King, Harlan Ellison, Ramsey Campbell and Clive Barker included—on their favorite genre books. This long-awaited second volume continues the tradition, with 100 new entries by the likes of Christopher Golden, Thomas Ligotti, Fangoria editor Anthony Timpone, China Mieville, cartoonist Gahan Wilson, Tim Lucas and many others. The books under discussion are all different from those covered in volume one (though with one out-and-out cheat: Tanith Lee’s essay on Arthur Machen’s TALES OF HORROR AND THE SUPERNATURAL, containing all the same stories featured in Machen’s HOUSE OF SOULS, which was already covered by T.E.D. Klein in the earlier book); they range from classics like THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY, ROSEMARY’S BABY, PET SEMATARY and THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS to lesser-known but equally worthy works like Sadegh Hedayat’s THE BLIND OWL, Robert F. Jones’ BLOOD SPORT and Michael Blumlein’s X,Y. Some of the selections are downright puzzling (I’ve never thought of George Gissing’s NEW GRUB STREET as a horror novel, although K.W. Jeter argues otherwise), others I flat-out disagree with (THE PLAYBOY BOOK OF HORROR AND THE SUPERNATURAL???), while other deserving titles are conspicuous by their absence (such as THE GOLEM, MALPERTUIS and DAGON, although all are listed in the “Recommended Reading” section, a vital resource in its own right). But despite whatever differences I might have with its contents, I can unhesitatingly commend this book as one of the absolute finest, most provocative genre references on the market.

First, here’s my nominee for BOOK OF THE YEAR. It’s not a horror novel, but rather a nonfiction anthology about horror novels: HORROR: ANOTHER 100 BEST BOOKS, edited by STEPHEN JONES & KIM NEWMAN (Carroll & Graf). It follows Jones & Newman’s seminal 1988 collection HORROR: 100 BEST BOOKS, which has long been a quintessential volume in my library, containing eradiate essays by leading horror writers—Stephen King, Harlan Ellison, Ramsey Campbell and Clive Barker included—on their favorite genre books. This long-awaited second volume continues the tradition, with 100 new entries by the likes of Christopher Golden, Thomas Ligotti, Fangoria editor Anthony Timpone, China Mieville, cartoonist Gahan Wilson, Tim Lucas and many others. The books under discussion are all different from those covered in volume one (though with one out-and-out cheat: Tanith Lee’s essay on Arthur Machen’s TALES OF HORROR AND THE SUPERNATURAL, containing all the same stories featured in Machen’s HOUSE OF SOULS, which was already covered by T.E.D. Klein in the earlier book); they range from classics like THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY, ROSEMARY’S BABY, PET SEMATARY and THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS to lesser-known but equally worthy works like Sadegh Hedayat’s THE BLIND OWL, Robert F. Jones’ BLOOD SPORT and Michael Blumlein’s X,Y. Some of the selections are downright puzzling (I’ve never thought of George Gissing’s NEW GRUB STREET as a horror novel, although K.W. Jeter argues otherwise), others I flat-out disagree with (THE PLAYBOY BOOK OF HORROR AND THE SUPERNATURAL???), while other deserving titles are conspicuous by their absence (such as THE GOLEM, MALPERTUIS and DAGON, although all are listed in the “Recommended Reading” section, a vital resource in its own right). But despite whatever differences I might have with its contents, I can unhesitatingly commend this book as one of the absolute finest, most provocative genre references on the market.

With that out of the way, let’s highlight J.G. BALLARD, who has for years been one of the most vital and  distinctive scribes on the scene. KINGDOM COME (Fourth Estate) is his latest book, and, like his previous novel, ‘03’s MILLENIUM PEOPLE, is at the moment only available in the author’s native England, meaning interested parties in the US will have to order it through UK or Canadian booksellers. Trust me, though, tracking it down will be well worth your while.

distinctive scribes on the scene. KINGDOM COME (Fourth Estate) is his latest book, and, like his previous novel, ‘03’s MILLENIUM PEOPLE, is at the moment only available in the author’s native England, meaning interested parties in the US will have to order it through UK or Canadian booksellers. Trust me, though, tracking it down will be well worth your while.

As with most of J.G. Ballard’s recent work, the subject of KINGDOM COME is English suburbia becoming infected with primitive anarchy—the opening line “The suburbs dream of violence” could effectively summarize Ballard’s last three books. The target here is consumerism, as exemplified by a British super mall called the Metro-Centre that has its own sports club and round-the-clock cable channel. The residents of the surrounding towns view the place as a veritable shrine, even after a maniac embarks on a shooting rampage in the Metro-Centre one morning. The protagonist is Richard Pearson, a renegade advertising executive whose father is killed in the shooting. Richard investigates the circumstances of the violence, moving into his father’s flat near the Metro-Centre, and in the process becomes increasingly involved in its hermetic universe of mindless consumerism and blind patriotism. Richard decides that, being the ad wiz he is, he’ll take over the place and use it for his own ends, signaling the novel’s major change in the formula pioneered by previous Ballard books like COCAINE NIGHTS and SUPER-CANNES, whose protagonists were passive observers to the madness around them. Here the main character takes a far more active role, becoming an unwitting neo-fascist as the violence and isolationism of the Metro-Centre’s patrons become ever more pronounced as a result of Richard’s all-too-effective advertising campaign.

KINGDOME COME is a powerful piece of work that often plays like a compilation of J.G. Ballard’s greatest hits: the early bits, with Richard gradually becoming aware of the secret culture of violence surrounding him, are right out of COCAINE NIGHTS, while the latter ones, in which the Metro-Centre’s patrons become isolated inside the mall and form a twisted universe within, could be outtakes from the author’s earlier HIGH RISE. Not that KINGDOM COME ever approaches those masterworks, but it does prove that Ballard, now well into his seventies, fully retains the descriptive skills and disarmingly prophetic imagination for which he’s become famous.

Next up is THREE DAYS TO NEVER by TIM POWERS (William Morrow), a wild, wooly, madcap supernatural romp. It centers on Frank Merrity, a middle-aged man visiting his Pasadena, CA childhood home, where his grandmother has just died, in the company of his telepathic daughter Daphne. It seems the house holds many a secret, including the fact that Marrity’s “Grammer” was the illegitimate daughter of no less than Albert Einstein, and furthermore held the key to a discovery Einstein kept hidden throughout his life: the secret of time travel, which resulted in the construction of a time machine Grammer kept in a shed behind her house. There’s also an Israeli cabal in search of the machine who will stop at nothing to get it. And there’s even more, including a mysterious blind woman who can “see” by invading the minds of others and looking through their eyes, a lucid severed head, an old man claiming to be Merrity’s father who is actually Merrity himself several years in the future, and a PEE WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE VHS encoded with vital info, not to mention an indescribably loopy narrative that mixes Hebrew mysticism, quantum physics, Shakespeare (THE TEMPEST in particular) and old Hollywood lore—did I mention Charlie Chaplin plays a part in the unfolding drama?

Next up is THREE DAYS TO NEVER by TIM POWERS (William Morrow), a wild, wooly, madcap supernatural romp. It centers on Frank Merrity, a middle-aged man visiting his Pasadena, CA childhood home, where his grandmother has just died, in the company of his telepathic daughter Daphne. It seems the house holds many a secret, including the fact that Marrity’s “Grammer” was the illegitimate daughter of no less than Albert Einstein, and furthermore held the key to a discovery Einstein kept hidden throughout his life: the secret of time travel, which resulted in the construction of a time machine Grammer kept in a shed behind her house. There’s also an Israeli cabal in search of the machine who will stop at nothing to get it. And there’s even more, including a mysterious blind woman who can “see” by invading the minds of others and looking through their eyes, a lucid severed head, an old man claiming to be Merrity’s father who is actually Merrity himself several years in the future, and a PEE WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE VHS encoded with vital info, not to mention an indescribably loopy narrative that mixes Hebrew mysticism, quantum physics, Shakespeare (THE TEMPEST in particular) and old Hollywood lore—did I mention Charlie Chaplin plays a part in the unfolding drama?

To the uninitiated this all might seem like an undisciplined mess. It helps if you’ve read Powers’ other books, in particular his Victorian time travel extravaganza THE ANUBIS GATES. No, THREE DAYS TO NEVER isn’t in the same league, lacking the freshness and cohesiveness of that book, but it is a pleasing and endlessly thought-provoking concoction which handily manages that most impossible of tasks: actually bringing something new to the hoary old time travel subgenre.

England’s great RAMSEY CAMPBELL appears to have recaptured the prolificacy of his early days, with  a new novel, SECRET STORY (Tor), appearing less than a year after his previous book, the turgid haunted bookstore chiller THE OVERNIGHT. By contrast, SECRET STORY is lively and energetic in the best Campbell tradition, straddling dark screwball comedy and intense horror in a manner similar to his 1991 novel THE COUNT OF ELEVEN. It also contains echoes of his masterpiece THE FACE THAT MUST DIE, with its “hero”, a severely misanthropic, maladjusted chap named Dudley Smith, bearing a more than passing resemblance to the former book’s homophobic serial killer protagonist Horridge.

a new novel, SECRET STORY (Tor), appearing less than a year after his previous book, the turgid haunted bookstore chiller THE OVERNIGHT. By contrast, SECRET STORY is lively and energetic in the best Campbell tradition, straddling dark screwball comedy and intense horror in a manner similar to his 1991 novel THE COUNT OF ELEVEN. It also contains echoes of his masterpiece THE FACE THAT MUST DIE, with its “hero”, a severely misanthropic, maladjusted chap named Dudley Smith, bearing a more than passing resemblance to the former book’s homophobic serial killer protagonist Horridge.

Dudley is a middle-aged civil servant who, living with his overprotective mother in Liverpool, writes morbid stories about murder and mayhem in his spare time, inspired by actual crimes he himself commits. His mother reads one of Dudley’s opuses and impulsively sends it off to a writing competition, where it unexpectedly wins first prize and is slated to be made into a movie. Not that this does anything to leaven Dudley’s disturbed mental state; in fact it only aggravates it when Dudley learns the family of the story’s real-life victim is suing the magazine that sponsored the contest, meaning he’ll have to come up with a new tale—in other words, Dudley will have to commit another murder he can transcribe. He sets his sights on an obnoxious feminist contributor to the magazine and then, when she’s killed in a car “accident”, on Patricia, the attractive editor overseeing his work. Patricia has no inkling of Dudley’s true nature until it’s too late, and neither do any of the other characters, from the overseers of the contest to Dudley’s own mother, all of whom are uniformly self-absorbed, self-deluding creeps. This doesn’t exactly make for a warm and cuddly read, but does make for an intriguing one that never takes a predictable turn. The reaction of Dudley’s mother late in the book when she discovers her son with a bound and gagged woman is one you definitely won’t expect, and nor is the subdued yet troubling capper, which suggests, TAXI DRIVER-like, that the world in general is every bit as deranged as Dudley.

Speaking of Campbell, we were graced in ’06 with a trade paperback edition of the above-mentioned THE FACE THAT MUST DIE, one of his key works, courtesy of Millipede. In it we’re introduced to Horridge, one of the most profoundly tragic and repellent fictional personages I’ve ever encountered, a paranoid bigot whose anti-social tendencies gradually, and horrifically, cross the line into murderous psychosis. The book showcases Campbell at his hallucinatory, psychologically astute finest, and features a new introduction by the author. My only beef with this edition is that it leaves out Campbell’s unforgettably macabre autobiographical essay “At The Back of My Mind: A Guided Tour”, which was included in the 1983 Scream/Press hardback and ’85 Tor paperback editions of this book. THE FACE THAT MUST DIE is certainly worthwhile by itself, but it’s become inextricably linked in my mind with the essay and admittedly seems somewhat lacking without it.

JACK KETCHUM is an author I’ve been championing since the early nineties, and it seems the rest of the world is finally catching on. Many of Ketchum’s older books have come back into mass market print, including SHE WAKES, THE GIRL NEXT DOOR and, in 2006, his classic OFF SEASON, originally published in truncated form back in 1980 and now restored to its original uncut glory by Leisure (reprinting the more expensive ‘00 Overlook Press edition). If you’ve never read this ass-kicker then now’s definitely the time to do so. It’s a tough, unbelievably savage brutality fest about a cannibalistic family living in upstate New York, and what happens when some clueless city dwellers elect to stay the weekend nearby. It was followed in 1991 by OFFSPRING, which was just republished in trade paperback form by Overlook. Not quite as potent as the previous book but still a royal head-knocker, it features descendants of OFF SEASON’S cannibals returning to the scene of the crime for another bloody chow-down. Meaty and satisfying, though I found the unconvincing happy ending a bit of a cop-out.

JACK KETCHUM is an author I’ve been championing since the early nineties, and it seems the rest of the world is finally catching on. Many of Ketchum’s older books have come back into mass market print, including SHE WAKES, THE GIRL NEXT DOOR and, in 2006, his classic OFF SEASON, originally published in truncated form back in 1980 and now restored to its original uncut glory by Leisure (reprinting the more expensive ‘00 Overlook Press edition). If you’ve never read this ass-kicker then now’s definitely the time to do so. It’s a tough, unbelievably savage brutality fest about a cannibalistic family living in upstate New York, and what happens when some clueless city dwellers elect to stay the weekend nearby. It was followed in 1991 by OFFSPRING, which was just republished in trade paperback form by Overlook. Not quite as potent as the previous book but still a royal head-knocker, it features descendants of OFF SEASON’S cannibals returning to the scene of the crime for another bloody chow-down. Meaty and satisfying, though I found the unconvincing happy ending a bit of a cop-out.

Jack Ketchum also had a brand new book in ’06, WEED SPECIES (Cemetery Dance). It’s a novella consisting of 86 pages of large printing—and copious illustrations by Glenn Chadbourne—that even the slowest reader can finish in under an hour. Still, what it lacks in girth this profoundly nasty little item more than makes up for in sheer mind-numbing horror. The author himself has dubbed WEED SPECIES his most extreme tale (no small claim!), and he may well be correct in that assessment. Based, like many of Ketchum’s works, on a true story, it begins in wrenching fashion, with the teenaged Sherry Jefferson drugging and stripping her little sister for her depraved boyfriend Owen to rape. Sherry and Owen mature into full-fledged sociopaths, jointly molesting unsuspecting young women and often killing them. Owen is captured halfway through the book and placed on death row, which is only a minor annoyance for Sherry, as she, having avoided incarceration by testifying against Owen, wastes no time finding another mate to induct into her campaign of illicit rape and murder. And there remain the disturbed victims who survived Sherry and Owen’s insanity and now have to contend with the fact that their lives have been permanently uprooted (hence the title). An absolute mind-roaster from one of the finest, most fearless authors in the business, who’s at his spare, unflinching best herein—but take heed: I’m dead serious when I say this book’s a mean one.

THE LOVELIEST DEAD by RAY GARTON (Leisure) is something of a departure for the illustrious  Garton in that it’s not a small press hardback (Garton might as well be named king of the small press) or movie novelization (a form this author has grown a bit too comfortable with in recent years). This creepy and involving novel debuted as a mass market paperback, which makes sense considering it’s one of Garton’s more commercial offerings, with his penchant for sex and gore toned down considerably. In standard Garton fashion, the narrative lifts familiar elements from several different sources—DON’T LOOK NOW, POLTERGEIST, THE SHINING—and blends them into a unique and cohesive whole about a distraught family moving into a forbidding house in Eureka, CA. It quickly becomes apparent that the place is haunted, as confirmed by a local psychic woman who senses a malevolent presence afoot. Apparently the spirit of a malicious pedophile lurks within the abode, along with those of the many kids he murdered. Deeply ominous, disquieting stuff that’s a bit leisurely and repetitive for my tastes (there are a few too many trips made back and forth from the accursed house by the psychic woman), but then I guess that’s the price the book pays for its staunch naturalism. Whatever faults his writing may have, Garton has really captured the flavor of life in Northern California as experienced by a lower middle class family, so much so that THE LOVELIEST DEAD would likely work fine without the supernatural business.

Garton in that it’s not a small press hardback (Garton might as well be named king of the small press) or movie novelization (a form this author has grown a bit too comfortable with in recent years). This creepy and involving novel debuted as a mass market paperback, which makes sense considering it’s one of Garton’s more commercial offerings, with his penchant for sex and gore toned down considerably. In standard Garton fashion, the narrative lifts familiar elements from several different sources—DON’T LOOK NOW, POLTERGEIST, THE SHINING—and blends them into a unique and cohesive whole about a distraught family moving into a forbidding house in Eureka, CA. It quickly becomes apparent that the place is haunted, as confirmed by a local psychic woman who senses a malevolent presence afoot. Apparently the spirit of a malicious pedophile lurks within the abode, along with those of the many kids he murdered. Deeply ominous, disquieting stuff that’s a bit leisurely and repetitive for my tastes (there are a few too many trips made back and forth from the accursed house by the psychic woman), but then I guess that’s the price the book pays for its staunch naturalism. Whatever faults his writing may have, Garton has really captured the flavor of life in Northern California as experienced by a lower middle class family, so much so that THE LOVELIEST DEAD would likely work fine without the supernatural business.

While on the subject of Ray Garton, his best-known book, 1987’s LIVE GIRLS, was republished by Leisure in ’06. I don’t agree with those who say it’s the author’s finest work (in my view Garton’s CRUCIFAX AUTUMN and TRADE SECRETS, both published shortly after this one made its initial appearance, are better), but it’s damn good, a nightmarish X-rated twist on traditional vampire mythos centering on a porno theater packed with bloodsucking babes. A must read for those who haven’t already done so–or even those who have!

I’ve largely kicked the DEAN KOONTZ habit, having decided I’d had enough after reading a dozen or so of his early books, although I find myself returning to his work on occasion. BROTHER ODD (Bantam) did not represent one of those occasions, but THE HUSBAND (Bantam) did, being a straightforward kidnapping thriller, something I’m always a sucker for. It concerns a gardener who receives a call from a man claiming he has his wife and will let her go for $2 million in cash…a mighty tall order for a gardener! He does his best to follow through with the bargain, however, particularly after a passerby is shot to demonstrate the seriousness of the kidnappers’ intent. What follows takes our mild-mannered hero (Koontz’s protagonists are always mild-mannered goody-goods) through a twisted odyssey of deceit, theft, murder and an examination of some decidedly frayed family ties. Whatever shortcomings he may have (and I say he’s got plenty), Koontz really knows how to do this kind of thing, delivering an unpretentious, fast-moving thriller with a respectable amount of suspense and breakneck action. Best of all is the fact that the premise demands the protagonist and his better half spend most of the book separated, meaning the sappy romance Koontz favors (a prime reason I gave up on his books all those years ago) is kept to a minimum. Alas, he can’t resist delivering his standard happy ending, with a forced and odiously sentimental coda.

I’ve largely kicked the DEAN KOONTZ habit, having decided I’d had enough after reading a dozen or so of his early books, although I find myself returning to his work on occasion. BROTHER ODD (Bantam) did not represent one of those occasions, but THE HUSBAND (Bantam) did, being a straightforward kidnapping thriller, something I’m always a sucker for. It concerns a gardener who receives a call from a man claiming he has his wife and will let her go for $2 million in cash…a mighty tall order for a gardener! He does his best to follow through with the bargain, however, particularly after a passerby is shot to demonstrate the seriousness of the kidnappers’ intent. What follows takes our mild-mannered hero (Koontz’s protagonists are always mild-mannered goody-goods) through a twisted odyssey of deceit, theft, murder and an examination of some decidedly frayed family ties. Whatever shortcomings he may have (and I say he’s got plenty), Koontz really knows how to do this kind of thing, delivering an unpretentious, fast-moving thriller with a respectable amount of suspense and breakneck action. Best of all is the fact that the premise demands the protagonist and his better half spend most of the book separated, meaning the sappy romance Koontz favors (a prime reason I gave up on his books all those years ago) is kept to a minimum. Alas, he can’t resist delivering his standard happy ending, with a forced and odiously sentimental coda.

Let’s turn our attention now to the King. STEPHEN KING to be exact, who had two novels out in ’06, CELL and LISEY’S STORY (both from Scribner). The two are poles apart, with the first being an apocalyptic splatter fest patterned after Richard Matheson’s I AM LEGEND and George Romero’s NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (the book is dedicated to Matheson and Romero). Unlike so much of King’s other recent fiction, CELL wastes no time getting to the good stuff: on the very first page cell phones around the world emit signals that turn their users into flesh-craving zombie-ish monsters. The remainder of the book is taken up with an intense, gore-packed trek across a ghoul-strewn landscape. As far as new wave zombie-fests go, this is a solid one, although I’d strongly recommend checking out the two abovementioned antecedents as, frankly, they’re better.

LISEY’S STORY is something else entirely, a long-winded fantasy love story that appears to be King’s latest grab for literary respectability (never mind that his last such attempts, HEARTS IN ATLANTIS and BAG OF BONES, failed to accomplish that goal), complete with critical blurbs by Nicholas Sparks and Nora Roberts. I’m admittedly still working my way through the early stages of the book, which thus far has been expansive and unfocused—but not uninteresting.

Another novel I haven’t gotten through is the 881-page THE SWARM by FRANK SCHATZING  (ReganBooks), an epic ecological chiller that was apparently a monster seller in the author’s native Germany. I’m currently about halfway into it. My verdict? So far, so good. The book may be a bit long-winded (it takes the story nearly 200 pages to really get moving), but is an extremely thoroughly researched, gripping account of microorganisms that turn peaceful marine animals into murderous beasts. It may sound outlandish, but the proceedings are vividly imagined and all-too convincing, especially considering many of the alarming real-life ecological developments of recent years.

(ReganBooks), an epic ecological chiller that was apparently a monster seller in the author’s native Germany. I’m currently about halfway into it. My verdict? So far, so good. The book may be a bit long-winded (it takes the story nearly 200 pages to really get moving), but is an extremely thoroughly researched, gripping account of microorganisms that turn peaceful marine animals into murderous beasts. It may sound outlandish, but the proceedings are vividly imagined and all-too convincing, especially considering many of the alarming real-life ecological developments of recent years.

If nothing else, the past year was a stellar one for zombie books. I feel this stuff has long since been done to death, although WORLD WAR Z: AN ORAL HISTORY OF THE ZOMBIE WAR by MAX BROOKS (Crown Publishers) and MONSTER ISLAND by DAVID WELLINGTON (Thunder’s Mouth Press) do their best to take the genre in new and interesting directions.

Max Brooks’ WORLD WAR Z, the follow-up to the author’s bestselling ZOMBIE SURVIVAL GUIDE, is a faux-history of a worldwide human-zombie conflict. Taking the living dead films of George Romero and the nonfiction compilations of Studs Terkel as his templates, Brooks weaves a fairly engrossing tapestry composed of fictional interviews with various survivors of the Zombie War. We hear from a Chinese doctor who treated the first recorded case of zombie-ism, an infected young boy; a CIA agent who attempts to rationalize the fact that his agency was late to take action during the crisis; a military man charged with turning white collar do-nothings into zombie killers; and a remembrance of a UN conference set on a floating aircraft carrier where the final decision in the war, to wage an all-out attack against the ghouls, was made. Along the way Brooks introduces many intriguing concepts, particularly “Quislings”, living people who think they’re zombies, and makes a number of relevant, real-world political points: yes, the many references to the Iraq War are all strictly intentional! The book, alas, may ultimately be a tad monotonous and inconsistent in its recollections—some, such as a National Guard commander’s near-twenty page reminisce, are inexplicably lengthy, while others, in particular a three-page account of the apparent disappearance of the entire population of North Korea, feel overly sparse. Max Brooks, the son of Mel, has wit and invention to spare, but this is one joke he may have allowed to run on a bit too long.

Max Brooks’ WORLD WAR Z, the follow-up to the author’s bestselling ZOMBIE SURVIVAL GUIDE, is a faux-history of a worldwide human-zombie conflict. Taking the living dead films of George Romero and the nonfiction compilations of Studs Terkel as his templates, Brooks weaves a fairly engrossing tapestry composed of fictional interviews with various survivors of the Zombie War. We hear from a Chinese doctor who treated the first recorded case of zombie-ism, an infected young boy; a CIA agent who attempts to rationalize the fact that his agency was late to take action during the crisis; a military man charged with turning white collar do-nothings into zombie killers; and a remembrance of a UN conference set on a floating aircraft carrier where the final decision in the war, to wage an all-out attack against the ghouls, was made. Along the way Brooks introduces many intriguing concepts, particularly “Quislings”, living people who think they’re zombies, and makes a number of relevant, real-world political points: yes, the many references to the Iraq War are all strictly intentional! The book, alas, may ultimately be a tad monotonous and inconsistent in its recollections—some, such as a National Guard commander’s near-twenty page reminisce, are inexplicably lengthy, while others, in particular a three-page account of the apparent disappearance of the entire population of North Korea, feel overly sparse. Max Brooks, the son of Mel, has wit and invention to spare, but this is one joke he may have allowed to run on a bit too long.

David Wellington’s MONSTER ISLAND, along with its follow-ups MONSTER NATION and MONSTER PLANET (the second is already in print and the third set for early ’07), originally appeared on the internet. I’ll admit that fact initially prejudiced me against the book (can you say hypocrite?), but I’m glad I finally came to my senses and gave it a chance. It’s the story of Dekalb, a onetime UN weapons inspector who explores the “island” of the title, New York City, in the company of a heavily armed group of schoolgirl soldiers. The world, it seems, has been overrun by the living dead and NYC is the only source for a heavily sought-after vaccine. But getting to the stuff is easier said than done, as zombies are everywhere, led by the power-mad Gary, a doctor who deliberately froze his body so he’d come back as a lucid ghoul. The fun really begins when Dekalb and the gals meet up with a ragtag band of surviving humans living in subway tunnels. Gary sends his undead minions after ‘em, leading to a mighty satisfying gore-on-the-floor showdown. Author David Wellington keeps things moving with imaginative elements like showerheads that spray gasoline (for a good ol’ zombie bonfire), reanimated museum mummies who take control (or try to) of the zombie hordes, and a vast monument built in the middle of Times Square in tribute to the ghouls. No, there’s nothing too deep here, just unpretentious living dead fun that’s action-packed and heavy on the sauce.

Something else we saw a lot of in ’06 were reprints of genre classics, like the abovementioned FACE THAT MUST DIE, OFF SEASON and LIVE GIRLS, as well as the equally vital tomes SOME OF YOUR BLOOD by THEODORE STURGEON (Millipede), RAPTURE by THOMAS TESSIER (Leisure), THE CELLAR by RICHARD LAYMON (Leisure), THE TENANT by ROLAND TOPOR (Millipede), FALLING ANGEL by WILLIAM HJORTSBERG (Millipede), STRANGE SEED by T.M. WRIGHT (Twisted Publishing), CELLARS by JOHN SHIRLEY (Writers.com) and, going way back, the 1911 FANTOMAS by MARCEL ALLAIN and PIERRE SOUVESTRE (Dover).

SOME OF YOUR BLOOD (1961) by the late, great Theodore Sturgeon, is among the few truly important  horror texts, an absolutely essential read. It was light years ahead of its time; for that matter, I believe our current literary establishment has yet to entirely catch up with it. Some might label SOME OF YOUR BLOOD a vampire novel—or more accurately novella—but in reality it’s a gruesome, thought-provoking and touching look at the tragic life of a swamp-dwelling young man with some decidedly bestial tendencies. The climax, which provides the title, is a knock-out.

horror texts, an absolutely essential read. It was light years ahead of its time; for that matter, I believe our current literary establishment has yet to entirely catch up with it. Some might label SOME OF YOUR BLOOD a vampire novel—or more accurately novella—but in reality it’s a gruesome, thought-provoking and touching look at the tragic life of a swamp-dwelling young man with some decidedly bestial tendencies. The climax, which provides the title, is a knock-out.

Thomas Tessier is another of those little-known authors whose work I’ve been championing for years. Leisure’s republication of RAPTURE, initially published back in 1987, follows their triumphant ’05 edition of Tessier’s 1986 masterpiece FINISHING TOUCHES. RAPTURE is nearly as fine, being a disturbing glimpse into the psyche of Jeff Lisker, a successful businessman and all-around lunatic fixated on an old high school crush and determined to make her his own, at whatever the cost. The result is an excellent psychological horror story that’s never less than totally convincing—not to mention extremely difficult to put down. Now if only someone would reprint Tessier’s 1997 stunner FOGHEART, or, even better, his 1980 lycanthropy-themed mind-roaster THE NIGHTWALKER. We can only hope…

Richard Laymon’s 1979 THE CELLAR was the first of the author’s many splatter fests, and in my view one of the best. The very definition of relentless, it follows a young woman and her young daughter, on the run from an abusive husband, who wind up in the “Beast House”, a secluded abode where a horror awaits that’s infinitely worse than the one the protagonists are fleeing. Kudos to Leisure for reintroducing long-unavailable books like this one to a mass audience—let’s hope they keep up the trend!

Millipede Press also deserves a mention here for reprinting quite a few must-reads from years past. The new editions of the above-mentioned FACE THAT MUST DIE and SOME OF YOUR BLOOD were under Millipede’s imprint, as was a fresh printing of Roland Topor’s brilliant, underrated THE TENANT from 1964, the basis of Roman Polanski’s film of the same name. The book is definitely a stand-alone work, being a superbly shivery depiction of paranoia and madness. The central character is Trelkovsky, a mousy young man who moves into a creepy building whose occupants, he begins to suspect, are conspiring to turn him into his apartment’s previous tenant, a young woman who committed suicide. Trelkovsky’s gradual descent into madness is rendered in chillingly concise prose, with a number of nightmarish interludes. A little-known classic newly introduced by that modern master of apprehension Thomas Ligotti, whose debt to this novel is obvious.

Also from Millipede was the latest edition of William Hjortsberg’s oft-reprinted 1978 masterwork FALLING ANGEL. It was and remains the absolute pinnacle of hard-boiled horror, with its private dick hero Harry Angel contacted by the eccentric Louis Cyphere to track down a renegade musician named Johnny Favorite. Scary business is in store for Angel, in a New York City beset with arcane black magic and supernatural mystery. The book was the genesis of the popular but inferior film ANGEL HEART; it made the mistake of transplanting the action to the American South, whereas one of the book’s intriguing qualities is its evocation of backwoods sorcery amidst the urban bustle of NYC. It’s a stunner in any event, with an intro by moviemaker Ridley Scott.

Also from Millipede was the latest edition of William Hjortsberg’s oft-reprinted 1978 masterwork FALLING ANGEL. It was and remains the absolute pinnacle of hard-boiled horror, with its private dick hero Harry Angel contacted by the eccentric Louis Cyphere to track down a renegade musician named Johnny Favorite. Scary business is in store for Angel, in a New York City beset with arcane black magic and supernatural mystery. The book was the genesis of the popular but inferior film ANGEL HEART; it made the mistake of transplanting the action to the American South, whereas one of the book’s intriguing qualities is its evocation of backwoods sorcery amidst the urban bustle of NYC. It’s a stunner in any event, with an intro by moviemaker Ridley Scott.

STRANGE SEED was the premiere novel by T.M. Wright, who’s gone on to become one of the most prolific and individual modern genre scribes. This book, from 1978, adequately set the tone for what was to come with its surreal evocation of a young couple’s encounter with some creepy humanoid children. A bit like VILLAGE OF THE DAMNED on acid, it was followed by three sequels. The new edition contains an introduction by Jack Ketchum, whose graphic and unflinching style is 180 degrees removed from the poetic, introspective brand of horror pioneered by this book.

CELLARS by John Shirley originally appeared in 1982, and was a seminal, if unacknowledged, entry in the splatterpunk movement. Just as the author’s early sci fi novels TRANSMANIACON and CITY COME A WALKIN’ anticipated William Gibson’s cyberpunk bible NEUROMANCER (something Gibson fully admits), so does CELLARS foreshadow Clive Barker’s “The Midnight Meat Train” and virtually the entire oeuvre of splat packers like John Skipp, Craig Spector and Edward Lee (who introduces this new edition). It’s a gritty account of subway-based supernatural horror set in a pre-gentrified Alphabet City. This new edition is said to be substantially revised from the original, which as I recall was pretty damn potent in its own right. Incidentally, CELLARS was just one of several John Shirley books to appear in ’06–others include a new edition of his 1989 interplanetary mind-bender A SPLENDID CHAOS, two novels set in the HELLBLAZER universe as well as BATMAN and PREDATOR entries. About those books I’ve heard mostly good things, but it does kinda suck that guys like Barker and Gibson are writing their own tickets (deservedly, of course) while Shirley, who came first, is stuck cranking out paperback quickies.

FANTOMAS by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre isn’t exactly difficult to obtain, but I’m glad Dover has brought this 1911 benchmark back into print in its original and definitive 1915 English translation (as opposed to the late eighties William Morrow edition, which suffered from a heavily edited, modernized English adaptation). Fantomas is of course the French “Lord of Terror” who appeared in 32 books written by the newspaper hacks Allain and Souvestre, as well as another 11 by Allain. This is the book that started it all, and it remains an irresistible page turner: scary, surreal and furiously paced. In it we’re introduced to the shadowy Fantomas, his sometime accomplice Lady Beltham, and his foils, the reporter Fandor and police inspector Jude, all caught up in a lightning-paced, feverishly inventive tale of criminal doings in early Twentieth Century Paris.

2006 was a good year to be a Fantomas fan, as in addition to the above, THE DAUGHTER OF  FANTOMAS appeared, published by Black Coat Press. The eighth entry in the series, and one of 11(!) FANTOMAS books from the year 1911, it has never before appeared in English. After reading it all I can say is, thank God it’s here at last! In it the evil Fantomas is literally dug up by the none-too-good Lady Beltham, just as the heroic Fandor finds himself unjustly interned in an insane asylum and the latter’s sidekick Inspector Jude arranges a fortuitous meeting with the title character aboard a cruise ship. From there Fantomas unleashes Bubonic Plague upon the ship’s residents in order to off Jude and Fandor busts out of the asylum with the help of a young man named Teddy. There’s also a skull everyone is after, a long-lost offspring Fantomas is searching for, a climb up a tree crawling with poisonous snakes, a central character who unexpectedly switches genders in the third act (leading to an equally unexpected romance), and more shocking revelations, narrow escapes and double-crosses than I can count. It’s the very essence of pulp fiction, and further benefits from an excellent translation by Mark P. Steele, who wisely refrains from updating the original text or attempting to improve upon it. The charming crudeness of the FANTOMAS books, after all, is a large part of their allure, as is fully evident in this fervid, outrageous and totally irresistible blast of pure sensationalism.

FANTOMAS appeared, published by Black Coat Press. The eighth entry in the series, and one of 11(!) FANTOMAS books from the year 1911, it has never before appeared in English. After reading it all I can say is, thank God it’s here at last! In it the evil Fantomas is literally dug up by the none-too-good Lady Beltham, just as the heroic Fandor finds himself unjustly interned in an insane asylum and the latter’s sidekick Inspector Jude arranges a fortuitous meeting with the title character aboard a cruise ship. From there Fantomas unleashes Bubonic Plague upon the ship’s residents in order to off Jude and Fandor busts out of the asylum with the help of a young man named Teddy. There’s also a skull everyone is after, a long-lost offspring Fantomas is searching for, a climb up a tree crawling with poisonous snakes, a central character who unexpectedly switches genders in the third act (leading to an equally unexpected romance), and more shocking revelations, narrow escapes and double-crosses than I can count. It’s the very essence of pulp fiction, and further benefits from an excellent translation by Mark P. Steele, who wisely refrains from updating the original text or attempting to improve upon it. The charming crudeness of the FANTOMAS books, after all, is a large part of their allure, as is fully evident in this fervid, outrageous and totally irresistible blast of pure sensationalism.

THE RUINS by SCOTT SMITH (Alfred A. Knopf) is the author’s long in the works (thirteen years!) follow-up to his bestselling 1993 debut A SIMPLE PLAN. This second novel isn’t as effective, suffering as it does from a relentlessly uneventful, painfully drawn-out storyline, essentially (as Stephen King concedes in his otherwise enthusiastic Amazon.com write-up) a short story stretched to novel length. That’s not to say the book doesn’t have its strengths: Smith is a mighty fine writer, and knows how to conjure a steadily building horrific atmosphere from just a few lines (which makes it all the more puzzling that he so mercilessly drags things out here). The narrative, related without chapter breaks or shifts in locale, follows two American couples vacationing in Mexico who follow a renegade companion to the sight of some ancient Mayan ruins…where a malevolent something awaits. I won’t give away what that something is (not that there’s much to give away), but will reveal the tale is a harrowing one that grows increasingly ugly as it advances, with starvation, makeshift amputations, self-mutilation, insanity and the ever-present specter of cannibalism all becoming apparent. Strong stuff, if a bit overdone.

The year’s biggest disappointment? CANDLES BURNING by TABITHA KING and MICHAEL McDOWELL (Berkley), an unfinished manuscript by the late McDowell (who died in 1999) that was completed by King. I really should have known better than to get my hopes up for this one, as I’m well aware that novels recovered after an author’s death rarely satisfy. True, McDowell during his lifetime was one of the finest genre scribes on the scene, and certain elements here confirm that: the characterizations are uniformly solid and the mid-Twentieth Century Southern milieu extremely well evoked. But from the start something is seriously off in this bloated tale of a young girl’s coming of age in the shadow of the suspicious murder of her father and her subsequent internment in a house haunted by the unquiet spirit of her grandmother. With its dense, overly labored descriptions and near-intolerably slow pacing, the writing woefully lacks the author’s usual energy; it seems McDowell died not only before his tale was complete, but before he had a chance to do any revisions. As for Tabitha King’s contributions, they’re evident by the halfway mark, when the heroine suddenly goes from a passive observer to a feminist fireball, and develops telepathic powers in the bargain. Not that this improves the sluggishness of the narrative, which limps to a real snooze of an ending.

The year’s biggest disappointment? CANDLES BURNING by TABITHA KING and MICHAEL McDOWELL (Berkley), an unfinished manuscript by the late McDowell (who died in 1999) that was completed by King. I really should have known better than to get my hopes up for this one, as I’m well aware that novels recovered after an author’s death rarely satisfy. True, McDowell during his lifetime was one of the finest genre scribes on the scene, and certain elements here confirm that: the characterizations are uniformly solid and the mid-Twentieth Century Southern milieu extremely well evoked. But from the start something is seriously off in this bloated tale of a young girl’s coming of age in the shadow of the suspicious murder of her father and her subsequent internment in a house haunted by the unquiet spirit of her grandmother. With its dense, overly labored descriptions and near-intolerably slow pacing, the writing woefully lacks the author’s usual energy; it seems McDowell died not only before his tale was complete, but before he had a chance to do any revisions. As for Tabitha King’s contributions, they’re evident by the halfway mark, when the heroine suddenly goes from a passive observer to a feminist fireball, and develops telepathic powers in the bargain. Not that this improves the sluggishness of the narrative, which limps to a real snooze of an ending.

CANDLES BURNING is masterpiece, however, compared with HANNIBAL RISING by THOMAS HARRIS (Delacorte), for me the year’s worst novel by far. I wanted to like it, being a huge fan of Harris’ earlier books (all four of ‘em), and tried to convince myself throughout that it wasn’t really as bad as it seemed. Told in short, crudely written chapters, it recounts the early years of Hannibal Lecter, who this book would have us believe was rousted from his cozy Eastern European home by Nazis, one of whom killed (and ate!) his sister. Young Hannibal ends up in the care of his uncle and the latter’s wife, a seductive Japanese woman named Lady Muraski, with whom Hannibal strikes up an affair. He still, however, seeks revenge for what was done to him as a child…and gets it.

The above adequately sums up the achingly simplistic narrative, which has NONE of the macabre invention or psychological complexity of Harris’ earlier books. The author constantly adds new and uninteresting characters that invariably have little to do, while Hannibal himself inexplicably spends much of the book offstage. Is this really any way to treat one of the most enduring characters in horror history? It’s been rumored that HANNIBAL RISING is essentially a novelization of the upcoming movie of the same title (set to be released in the spring of ’07). That would certainly explain the slapdash quality of the writing, but I really thought we could expect more from Thomas Harris, especially since it’s been seven years since his last book (admittedly a pretty fast turnaround by Harris standards, but still…). Inexcusable!

Better work was done by Japan’s KOJI SUZUKI with BIRTHDAY (Vertigo)—initially published back in  1999, it’s the fourth entry in his RING cycle. It’s a short book consisting of three interrelated stories, all centered on women and all revolving around themes of birth. The action commences with “Coffin in the Sky”, headlined by Mai Takano, distraught lover of Ryuji Takayama (the protagonist of the first RING book); while searching for clues about the latter’s untimely disappearance Mai falls into a confined space and unexpectedly gives birth. “Lemon Heart” follows, about the early years of Sadako Yamamura, the villainess of the RING universe. We follow Yamamura as a young actress in a theatrical production where she learns how to psychically imprint her voice on an audiotape, which as anyone familiar with the RING mythos well knows, has horrific implications. “Happy Birthday” is the final story, told from the point of view of Reiko Segiura, the wife of Kaoru Futami, the hero of the third RING book LOOP. Futami it seems has disappeared into the Loop, an alternate computer generated reality, leaving Reiko alone to birth their baby. However, she finds a way into the Loop to communicate with her beloved one last time…

1999, it’s the fourth entry in his RING cycle. It’s a short book consisting of three interrelated stories, all centered on women and all revolving around themes of birth. The action commences with “Coffin in the Sky”, headlined by Mai Takano, distraught lover of Ryuji Takayama (the protagonist of the first RING book); while searching for clues about the latter’s untimely disappearance Mai falls into a confined space and unexpectedly gives birth. “Lemon Heart” follows, about the early years of Sadako Yamamura, the villainess of the RING universe. We follow Yamamura as a young actress in a theatrical production where she learns how to psychically imprint her voice on an audiotape, which as anyone familiar with the RING mythos well knows, has horrific implications. “Happy Birthday” is the final story, told from the point of view of Reiko Segiura, the wife of Kaoru Futami, the hero of the third RING book LOOP. Futami it seems has disappeared into the Loop, an alternate computer generated reality, leaving Reiko alone to birth their baby. However, she finds a way into the Loop to communicate with her beloved one last time…

The RING texts are key works of modern horror, and if your only contact with them is through the movie versions than you owe it to yourself to check out the books. Don’t start with BIRTHDAY, though, as it’s ultimately more of an addendum to the series than a legitimate edition. Koji Suzuji, you see, effectively destroyed the world in the first two novels and then posited, in LOOP, the third and most outrageous book, that that world was contained within the virtual reality universe of the Loop, leaving himself with nowhere left to go in this fourth and (I hope) final entry. It is worth perusing, though, if only to once again experience Suzuki’s far-out yet curiously methodical imagination (and in a better-than-usual English translation), which renders truly crazed flights of fancy with the logic and precision of a science fiction author—just make sure you read the other three novels first

Another Japanese horror work appearing for the first time in English, and again from Vertigo, is THE CRIMSON LABYRINTH by YUSUKE KISHI. It’s one of those books one reads thinking how good it could have been but isn’t. For example, this morbid account of several Japanese professionals who wake up one morning in the Australian outback would have really benefited from more action. Author Yusuke Kishi devotes far too much time to the game consoles the characters find in their possession and the detailed instructions provided by those consoles, which ultimately don’t have much bearing on the story. That story turns into an all-out struggle for survival when the characters split up into different camps; a few of the people eat contaminated biscuits that turn them into bug-eyed cannibalistic beasts, which increases the stakes considerably. Despite that, though, the tale woefully lacks the relentlessness you might expect, and nor is its ultimate explanation, revealed in the final pages, all that shocking (at least to anyone remotely familiar with the reality TV trend that has taken off in the years since this book was initially published). It’s not entirely bad, being a smooth and clever read, but could have been so much better.

2006 saw another Vertigo publication, the long-awaited English language appearance of PARASITE EVE by HIDEAKI SENA. This book initially appeared back in 1995 and was quite a groundbreaker on the Japanese horror scene. Ten years later it remains a startling piece of work that begins like a Michael Crichton potboiler, with a woman killed by an unknown virus. One of her kidneys is transplanted into the body of a teenage girl while the woman’s aggrieved pharmaceutical professor husband decides to keep a sample of her liver in his lab. The woman, however, had no ordinary disease; it turns out she was infected with nothing less than “Mitochondrial Eve”, the mitochondria from which humanity originated. It seems Eve has become tried of doing the bidding of her host organism and has decided to take over–hence the second half of the book, which turns into a Cronenbergian freak-out as the cells in the liver sample form themselves into a living entity determined to impregnate the young woman who received the liver transplant and use the offspring to take over the world. PARASITE EVE’S English translation leaves much to be desired, done in unimaginative, children’s book fashion, although a large part of the book’s power, it must be added, comes from the straightforwardness of its prose, which is unnervingly calm and rational even when describing melting body parts and sub-human copulation. I’ll confess parts of it went over my head; the author was a Pharmacology graduate student when he wrote it and includes a wealth of terms and procedures incomprehensible to all but the most knowledgeable biologists (a glossary is helpfully included). Still, at its best PARASITE EVE is a stunner: grotesque, disturbing and quite possibly prophetic.

2006 saw another Vertigo publication, the long-awaited English language appearance of PARASITE EVE by HIDEAKI SENA. This book initially appeared back in 1995 and was quite a groundbreaker on the Japanese horror scene. Ten years later it remains a startling piece of work that begins like a Michael Crichton potboiler, with a woman killed by an unknown virus. One of her kidneys is transplanted into the body of a teenage girl while the woman’s aggrieved pharmaceutical professor husband decides to keep a sample of her liver in his lab. The woman, however, had no ordinary disease; it turns out she was infected with nothing less than “Mitochondrial Eve”, the mitochondria from which humanity originated. It seems Eve has become tried of doing the bidding of her host organism and has decided to take over–hence the second half of the book, which turns into a Cronenbergian freak-out as the cells in the liver sample form themselves into a living entity determined to impregnate the young woman who received the liver transplant and use the offspring to take over the world. PARASITE EVE’S English translation leaves much to be desired, done in unimaginative, children’s book fashion, although a large part of the book’s power, it must be added, comes from the straightforwardness of its prose, which is unnervingly calm and rational even when describing melting body parts and sub-human copulation. I’ll confess parts of it went over my head; the author was a Pharmacology graduate student when he wrote it and includes a wealth of terms and procedures incomprehensible to all but the most knowledgeable biologists (a glossary is helpfully included). Still, at its best PARASITE EVE is a stunner: grotesque, disturbing and quite possibly prophetic.

Speaking of long-awaited books: the Russian bestseller NIGHT WATCH by SERGEI LUKYANENKO (Miramax), the basis of the smash hit film of the same name, took eight years to reach the English speaking world, but it’s here at last, and I’ve read and enjoyed it immensely. It’s a wholly unique work, being a hip, fast-moving, unfailingly inventive account of a young man who’s an “Other” (a supernaturally-endowed individual) working for the Night Watch, a band of Others who spend their nights keeping Moscow’s population of vampires, werewolves and other evil beasties at bay—but once the sun rises the Day Watch takes over to keep the good guys in line. In this way an uneasy truce is kept between the forces of light and darkness, with both Watches saddled with a rigorous set of rules. It seems, however, that one faction is always trying to tip the balance, be it through a cursed woman with a gigantic vortex swirling over her head that threatens to overwhelm everything in its path or an Other who kills agents of darkness without understanding his true nature, thus unwittingly giving the Day Watchers a perfect chance to frame the protagonist and his cohorts for the murders. Sounds complicated, and indeed it is, but it’s all meticulously worked out. Author Sergei Lukyanenko is a stickler for detail, and creates a fully realized, vivid and satisfying universe of good and evil, but the book is first and foremost a damn good read, with a plethora of violence, intrigue and even some soulful introspection. Unexpectedly, the final pages forsake the action framework of much of the rest of the narrative to close things out on a subdued and contemplative note, which turns out to be just what the material needs. BTW, NIGHT WATCH is the first of a trilogy, with part two due to appear in early 2007—I for one am anxiously awaiting its publication.

Switching gears, we arrive at THE ROAD by CORMAC McCARTHY (Knopf), a decidedly more literate  and mature novel, but one packed with horrors a’plenty. It’s another tough, unsparing look at brute survival in a primitive land by McCarthy, who has, uncharacteristically, been quite prolific these days (with this novel following his last, NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN, by less than year). Unlike McCarthy’s standard fare, THE ROAD is set not in frontier days but in the future, in an America devastated by nuclear war. It follows an unnamed man and his young son as they traverse this ravaged setting, foraging for sustenance in abandoned houses, campsites and a moored ship, fighting off savage intruders and desperately attempting to find a reason to continue on (“There were few nights lying in the dark”, McCarthy writes of his protagonist, “that he did not envy the dead”). There’s no story to speak of, just a collection of incidents, some gruesome and some poignant, set in the most unforgiving landscape imaginable.

and mature novel, but one packed with horrors a’plenty. It’s another tough, unsparing look at brute survival in a primitive land by McCarthy, who has, uncharacteristically, been quite prolific these days (with this novel following his last, NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN, by less than year). Unlike McCarthy’s standard fare, THE ROAD is set not in frontier days but in the future, in an America devastated by nuclear war. It follows an unnamed man and his young son as they traverse this ravaged setting, foraging for sustenance in abandoned houses, campsites and a moored ship, fighting off savage intruders and desperately attempting to find a reason to continue on (“There were few nights lying in the dark”, McCarthy writes of his protagonist, “that he did not envy the dead”). There’s no story to speak of, just a collection of incidents, some gruesome and some poignant, set in the most unforgiving landscape imaginable.

Yes, THE ROAD is about as bleak as they come, and, unlike many better-known science fictionish treatments of a post-nuke existence, is staunchly reality-based (meaning it’s a long way from DAMNATION ALLEY). It also features all manner of nastiness (a baby’s corpse charred over an outdoor fire, a pit of writhing snakes collectively burned to death, and countless corpses and miscellaneous body parts encountered by our increasingly jaded duo), making it a strictly not-for-the-squeamish read. But it’s still a gripping account by one of our most consistently dependable authors. Cormac McCarthy’s stripped-down, poetic vernacular is among the most virtuosic and distinctive in existence, and THE ROAD is as powerful as nearly anything else he’s written.

Making another 180-degree turn, let’s take a look at THE SERIAL KILLERS CLUB by JEFF POVEY (Warner). Those wanting a realistic look at the lives and/or motives of serial killers will be put off by this darkly comedic novel from British TV scribe Jeff Povey, but for everyone else it’ll be an amiably twisted treat. It has an irresistible set-up involving a dude getting attacked by a “skiller” and killing the psycho in the act. Going through the attacker’s wallet, the protagonist finds a personal ad about a serial killers club held in Chicago; assuming the dead guy’s identity, he travels there and joins the club, which holds weekly get-togethers in a posh restaurant. The members include eighteen notorious skillers, each known by the name of a famous movie star–our hero, who christens himself “Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.”, grows to enjoy the club meetings amidst luminaries like “Errol Flynn”, “William Holden”, “Richard Burton” and “Cher”. But trouble looms, in the form of an overly assiduous FBI agent who latches onto “Dougie”, believing he’s the skiller whose identity he borrowed. The solution? Kill everyone in the club, one by one. There are complications, including “Betty Grable”, a new member with whom Dougie falls in love, and the specter of the “Kentucky Killer”, a shadowy psychopath who even the club’s members are afraid of, and who, it seems, wants to join the party.

THE SERIAL KILLERS CLUB is a really funny book that had me laughing out loud at many points. It also contains more than its share of inventive killings, although, as they’re all visited upon serial killers, none are very troubling. The pacing is sprightly, the page count under 300 pages yet still meaty enough for the author’s purposes, and there are some unexpected twists toward the end. It’s a book that reads very much like a commercial movie, in particular a Hollywood thriller: lightweight but sinfully entertaining.

The hands-down award for the year’s most ungainly title goes to THE HORRIFIC SUFFERINGS OF THE MIND-READING MONSTER HERCULES BAREFOOT: HIS WONDERFUL LOVE AND HIS TERRIBLE HATRED, by CARL-JOHAN VALLGREN (HarperCollins). Don’t let that put you off, though, as the book is a picturesque, gruesome, phantasmagoric historical fable in the grand tradition of classics like PERFUME and GEEK LOVE. The central character is Hercules Barefoot, a hideously deformed mind-reading dwarf born to a prostitute on the same day as the beautiful Henriette Vogel, who becomes Herc’s one true love. It’s this overwhelming love that sustains Hercules after the two are separated as children and he’s interned first in an insane asylum and then a corrupt Jesuit monastery. But he manages to escape the clutches of his evil monk masters and, appropriately enough, joins a freak show. That’s only the first half of the book, which concludes with tragedy and vengeance as Hercules hones his psychic powers to increasingly horrific effect.

The hands-down award for the year’s most ungainly title goes to THE HORRIFIC SUFFERINGS OF THE MIND-READING MONSTER HERCULES BAREFOOT: HIS WONDERFUL LOVE AND HIS TERRIBLE HATRED, by CARL-JOHAN VALLGREN (HarperCollins). Don’t let that put you off, though, as the book is a picturesque, gruesome, phantasmagoric historical fable in the grand tradition of classics like PERFUME and GEEK LOVE. The central character is Hercules Barefoot, a hideously deformed mind-reading dwarf born to a prostitute on the same day as the beautiful Henriette Vogel, who becomes Herc’s one true love. It’s this overwhelming love that sustains Hercules after the two are separated as children and he’s interned first in an insane asylum and then a corrupt Jesuit monastery. But he manages to escape the clutches of his evil monk masters and, appropriately enough, joins a freak show. That’s only the first half of the book, which concludes with tragedy and vengeance as Hercules hones his psychic powers to increasingly horrific effect.

All in all a highly distinct piece of work that begins in a jaunty, almost whimsical manner before twisting itself into a horror story as intense as nearly any you’ll encounter, only to conclude in wistful and romantic fashion. It’s held together by the skill and assurance of Swedish author Carl-Johan Vallgren (and a crisp translation by Paul Austin and Veronica Britten-Austin), whose florid prose is never less than totally absorbing. The narrative arc may ultimately be a mite standard, especially in contrast to the uniqueness of the author’s overall vision, but that doesn’t lessen the novel’s transcendent effect. One of 2006’s standout books!

Those desiring single author anthologies got little satisfaction from the major publishers last year, but the indies thankfully took up the slack. 2006 saw the release of two independently published short story collections, AFTER DARK by JEANI RECTOR (PublishAmerica) and 20th CENTURY GHOSTS by JOE HILL (PS Publishing). Both showcase the work of new and interesting writers, and both are well worth your while.

AFTER DARK is a solid, satisfying collection of 13 old-school horror stories. “The Golem” in particular is a fine piece, an audacious take on the legend of the Golem, a living creature made from clay that according to Hebrew folklore defended the ghettoes of Sixteenth Century Prague. Other tales of note are the twisty “Horrorscope”, containing a surprise ending you won’t be able to predict no matter how hard you try; “Ghoul”, an imaginative account of a voodoo curse that likewise contains quite a few unexpected twists; “The Black Death”, a dark drama set in the time of the Bubonic Plague that decimated Fourteenth Century Europe; and “The Boogeyman”, about a boy who fears the you-know-what only to discover that a far greater real-life horror exists literally in his own backyard. Lesser entries include the interesting but fatally predictable “Night of the Banshee”; “The Kraken”, a limp drama starring the folkloric sea critter; and the novella-length “The Rye Witch”, although that one does at least succeed in rendering the Seventeenth Century Salem witch trials in concise and entertaining fashion, even if it is quite uneven.

a fine piece, an audacious take on the legend of the Golem, a living creature made from clay that according to Hebrew folklore defended the ghettoes of Sixteenth Century Prague. Other tales of note are the twisty “Horrorscope”, containing a surprise ending you won’t be able to predict no matter how hard you try; “Ghoul”, an imaginative account of a voodoo curse that likewise contains quite a few unexpected twists; “The Black Death”, a dark drama set in the time of the Bubonic Plague that decimated Fourteenth Century Europe; and “The Boogeyman”, about a boy who fears the you-know-what only to discover that a far greater real-life horror exists literally in his own backyard. Lesser entries include the interesting but fatally predictable “Night of the Banshee”; “The Kraken”, a limp drama starring the folkloric sea critter; and the novella-length “The Rye Witch”, although that one does at least succeed in rendering the Seventeenth Century Salem witch trials in concise and entertaining fashion, even if it is quite uneven.

As for Joe Hill’s 14-story collection 20th CENTURY GHOSTS, I’ll admit its inclusion is a bit of a cheat since it was actually published back in September of 2005, but the fact is I didn’t learn of its existence until well into the following year, and furthermore the book is still largely unknown to most horror fans. It’s a nicely-rounded compilation of subdued, Bradbury-esque pieces, most of them centered on children. They range from a tender tale of a boy’s encounter with the harsh realities of death (“The Widow’s Breakfast”) to a high-spirited pastiche of fifties B-movie clichés (“You Will Hear the Locust Sing”), a ghostly romance (“20th Century Ghost”) and two elegant exercises in obscurantism (“Dead-Wood” and “My Father’s Mask”). Not all the stories worked for me, in particular “The Black Phone” and “Abraham’s Boys”, formulaic accounts of abused boys striking back against their respective tormentors (both conclude with pithy, Dirty Harry-esque one-liners) that are simply not up to the high standards set by the rest of the book. There are, however, two bonafide masterpieces: “Voluntary Committal”, a poetic, dark-hued reminiscence of growing up with a schizophrenic relative obsessed with empty boxes, and the transcendent “Pop Art”, a breathtaking piece of surrealism about the travails of an inflatable boy that’s by itself worth the purchase.

Another worthy effort by a first-timer is CHASING THE DEAD by JOE SCHREIBER (Ballantine), a fast-paced, surprise-filled horror romp that begins as a straightforward kidnapping thriller and morphs into a superlative supernatural suspenser. Sue Young is the protagonist, a young mother drawn into a nightmare one night when while driving home from work she receives a cell phone call from an unknown male claiming he’s kidnapped her daughter. It seems Sue committed some horrific crime years earlier that she now has to pay for, which entails a marathon drive down the nighttime roads of New England. Of course, not all is as it seems—in fact, virtually nothing is, which makes for a head-snapping read packed with cold blooded murder, zombies, arcane voodoo rituals, demonic possession and a cliff-hanger at the end of every chapter. It also makes for an implausible and over-insistent narrative: the near-constant plot twists grow numbing after awhile, especially since by the end they cease to entirely make sense. The book is written with great skill and imagination to be sure, and I recommend it, but not to those with a low tolerance for unbelievable turnarounds.

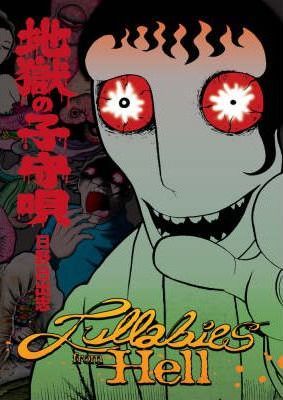

I’d be remiss if I didn’t pay lip service to the graphic novel field. 2006 saw the release of two stand-out GNs, the first being a manga, LULLABIES FROM HELL (Dark Horse) by the legendary HIDESHI HINO. For Hino fans the last few years have been good ones, with Dark Horse’s sixteen-volume Hino Horror collection appearing, as well as this new 4-part anthology, which contains some of his best recent work. If you’re unfamiliar with Hideshi Hino’s peerlessly twisted universe, understand that it’s among the most distinctive (with its utterly unique square headed, bug-eyed figures) and deeply twisted in or out of the Japanese manga universe. My first encounter with Hino’s deranged genius was via the profoundly shocking, revelatory PANORAMA OF HELL, published by Blast Books back in the eighties, and I’ve been eagerly searching out his work ever since.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t pay lip service to the graphic novel field. 2006 saw the release of two stand-out GNs, the first being a manga, LULLABIES FROM HELL (Dark Horse) by the legendary HIDESHI HINO. For Hino fans the last few years have been good ones, with Dark Horse’s sixteen-volume Hino Horror collection appearing, as well as this new 4-part anthology, which contains some of his best recent work. If you’re unfamiliar with Hideshi Hino’s peerlessly twisted universe, understand that it’s among the most distinctive (with its utterly unique square headed, bug-eyed figures) and deeply twisted in or out of the Japanese manga universe. My first encounter with Hino’s deranged genius was via the profoundly shocking, revelatory PANORAMA OF HELL, published by Blast Books back in the eighties, and I’ve been eagerly searching out his work ever since.

LULLABIES FROM HELL’s four tales are typically mind-scraping works containing all Hino’s trademarks: madness, graphic bloodletting, disgusting physical deformity, maggots, ghosts and wholesale mayhem a’plenty. The first part, which provides the title, is an “autobiographical” portrayal of Hino discovering he has the power to make his enemies die gruesome deaths; it ends with him cursing the reader, who in three days will apparently “die in a way more heinous than any murder I’ve committed so far!” (To the superstitious among you, don’t be too concerned–it’s been more than three days since I read those lines and I’m still here.) The second tale is “Unusual Fetus, My Baby”, a seriously gross piece of work about a frog-creature born to a seemingly normal woman. The thing feeds on animals and, inevitably, humans; its parents think their situation is an isolated incident, but it transpires that pollution is causing women all over the world to birth mutant children. Next up is “Train of Terror”, a hysterical rendering of a group of kids terrorized by an evil trench-coat wearing dude first encountered on a train. It contains some of Hino’s boldest, most expressive artwork, even if the story itself is something of a hodgepodge. The concluding tale is “Zoroku’s Strange Disease”, about a boy who metamorphoses into a disgusting insect-eating mutant, and as a result is shunned by his community. It’s a nasty tale even by traditional Hino standards, but ends on an unexpected note of real pathos that closes things out in memorably subdued fashion.

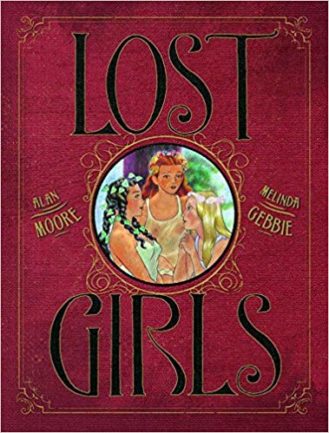

Lastly we have another, far weightier (in every sense of the word) graphic novel. It’s not exactly horror,  but comes highly recommended, even if it does carry a high price tag: a whopping $75.00! Furthermore, it will likely be completely sold out by the time you read this; perhaps it’ll be reprinted soon, and at a more reasonable price. It’s LOST GIRLS (Top Shelf Productions) scripted by ALAN MOORE, his first graphic novel (actually a three-book set) in many years, and illustrated by the famed underground artist MELINDA GEBBIE.

but comes highly recommended, even if it does carry a high price tag: a whopping $75.00! Furthermore, it will likely be completely sold out by the time you read this; perhaps it’ll be reprinted soon, and at a more reasonable price. It’s LOST GIRLS (Top Shelf Productions) scripted by ALAN MOORE, his first graphic novel (actually a three-book set) in many years, and illustrated by the famed underground artist MELINDA GEBBIE.

In fact this adults-only graphic saga was initiated back in 1991 and completed fifteen years later. It’s a visionary and frankly pornographic account of Alice (of ALICE IN WONDERLAND), Wendy (of PETER PAN) and Dorothy (from THE WIZARD OF OZ) meeting in a posh Victorian hotel in the days leading up to WWI. The ladies spend this uncertain period engaged in all manner of sex acts while spinning pervy variations on the fantasies they’re known for: Alice speaks of her adventures in a debauched boarding school and the “wondrous” sexual initiation she underwent there, Wendy relates her exploits with a young prostitute named Peter and an elderly letch with a hook-like hand, and Dorothy tells how she was molested by her “uncle” in the fields of Kansas while carrying on relationships with local boys who were made, respectively, smarter, more courageous and more sensitive by Dorothy’s sexual prowess. And that’s not all: there’s also plenty of amorous activity occurring in the hotel independent of the three protagonists, whose participants include two of the gals’ own husbands who become attracted to each other!

LOST GIRLS features nearly every imaginable type of perversion, but is far more than a simple dirty book. Rather, it’s a literate and intelligent celebration of Victorian-era erotica (with explicit references to practitioners like Aubrey Beardsley, Pierre Louys and Oscar Wilde), as well as a sophisticated dismantling of three of the western world’s most cherished fantasies. Moore’s aim here appears similar to those of Robert Deveraux’s SANTA STEPS OUT and Steven R. Boyett’s novelette EMERALD CITY BLUES: an all-out desecration of childhood icons in an effort to shock readers into a new maturity (a noble attempt, I’d say, in today’s climate). Aside from that, the artwork is eye-popping and the narrative genuinely erotic. On the downside, I found LOST GIRLS somewhat exasperating and ultimately perhaps too much of a good thing. A vital work nonetheless!

That, I’m afraid, is the last of the genre books I read in the year 2006. They were many I missed, of course, which I’ll briefly cover below.

There was SHARP OBJECTS by GILLIAN FLYNN (Shaye Areheart), a dysfunctional family thriller by Entertainment Weekly‘s TV reviewer that comes with an enthusiastic write-up by Stephen King. The teens-in-jeopardy freak-out THE HARROWING, by veteran screenwriter ALEXANRA SOKOLOFF (St. Martin’s Press), also received its share of enthusiastic press, with back cover blurbs from the likes of Ramsey Campbell and Peter Straub. THE KEEPER by SARAH LANGAN (HarperTorch), about a haunted town in Maine, is another novel by a first-timer whose cover is likewise adorned with blurbs a’plenty.

The giant earthworm chiller THE CONQUEROR WORMS by BRIAN KEENE (Leisure), looks like it might be fun, as does the postmodern horror fest DEMON THEORY by STEPHEN GRAHAM JONES (MacAdam/Cage), which appears similar to Mark Danielewski’s loopy classic HOUSE OF LEAVES. Speaking of MARK Z. DANIELEWSKI, he just published a new book, the near-incomprehensible pretention-fest ONLY REVOLUTIONS (Pantheon), of which I’ve only been able to get through a few pages.

J.F. GONZALEZ, author of the 2005 gut-wrencher SURVIVOR (which appeared in paperback in early ’06), was back with THE BELOVED (Leisure), a supernatural gore fest. JOHN SKIPP, formerly of Skipp & Spector, put out a new splatter-thon, THE LONG LAST CALL (Cemetery Dance), which comes with the attention-getting tagline “It’s the degradest show on Earth!” There was also DARK HARVEST by NORMAN PARTRIDGE (Cemetery Dance). Partridge’s horror excursions have become fairly rare, but they’re always worth seeking out; this one has already received much effusive praise, having been named one of the year’s best books by Publisher’s Weekly.

I’ve long been interested in Erzsbet Bathory, the notorious Hungarian “Blood Countess” who allegedly bathed in the blood of hundreds of virgins, and so couldn’t help but be intrigued by THE TROUBLE WITH THE PEARS: AN INTIMATE PORTRAIT OF ERZSBET BATHORY by GIA BATHORY AL BABEL (Authorhouse), particularly since the author shares her subject’s last name—but then, the only info I’ve been able to glean about this book was from sub literate Amazon.com readers’ reviews, which are far from promising. If you happen to read this one, please do me a favor and let me know how it is.