For fiction, 2011 was an only slightly better year than it was for movies—and cinematically it was a pretty rotten year. Below you’ll find the latest installment of my annual Year in Horror Fiction overview. It’s considerably shorter than most of my previous YIHFs, for which there are several reasons (one of which is made clear in the “Books I couldn’t Get Through” section that concludes this piece).

So let’s get started with…

My Favorites

The time travel opus 11/22/63 by STEPHEN KING (Scribner) was my favorite book of 2011. It may well be the most sheerly enjoyable novel King has ever written, being in the same league with time travel classics like Jack Finney’s TIME AND AGAIN and Ken Grimwood’s REPLAY.

The time travel opus 11/22/63 by STEPHEN KING (Scribner) was my favorite book of 2011. It may well be the most sheerly enjoyable novel King has ever written, being in the same league with time travel classics like Jack Finney’s TIME AND AGAIN and Ken Grimwood’s REPLAY.

The overall concept is simple enough: Jake Epping, a 35-year-old Maine based English teacher, is encouraged by Al, a fry cook, to travel back in time to prevent the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It just so happens that a time portal exists in the back room of Al’s diner that leads back to the year 1958. Long story short: Jake makes the attempt. Before doing so, however, he decides to prevent another past tragedy involving an adult student whose father took a hammer to his family, which conveniently occurred in 1958.

The latter plot strand takes up much of the opening third, which sees Jake settling in the fictional town of Derry, Maine (the setting, you may recall, of King’s IT). Following this Jake makes his way to Texas, where Lee Henry Oswald will (allegedly) shoot JFK from a Dallas book depository on November 22, 1963. In the meantime Jake falls in love and finds fulfillment in early-1960s Texas by working as a teacher in the friendly town of Jodie, which complicates his quest immeasurably.

That’s all I’ll reveal of this epic narrative (of which I’ve probably given away too much). King rigorously follows the laws of time travel, even if he ultimately doesn’t add a whole lot to the subgenre. 11/22/63’s pleasures are in its unerringly enjoyable narrative, which nicely blends nostalgia, romance and horror. Its portrait of late 1950s-early 1960s America is impressively vivid and atmospheric, and the novel furthermore contains one of King’s most satisfying endings in some time.

My other favorite read of 2011 was WILLY by ROBERT DUNBAR (Uninvited Books), which is  everything King’s novel isn’t: demanding, introspective and deeply weird, a definite thinking person’s horror story. It’s told in the form of diary entries by a deeply troubled teen boy sent to a rural boarding school. This kid’s diary, with its shaky grammar, free-form composition and numerous crossed-out words, is among the only truly convincing fictional depictions of the voice and world view of a teenager that I’ve encountered.

everything King’s novel isn’t: demanding, introspective and deeply weird, a definite thinking person’s horror story. It’s told in the form of diary entries by a deeply troubled teen boy sent to a rural boarding school. This kid’s diary, with its shaky grammar, free-form composition and numerous crossed-out words, is among the only truly convincing fictional depictions of the voice and world view of a teenager that I’ve encountered.

After around 50 pages’ worth of entries laying out the protagonist’s disturbed mind-set we meet Willy. As described by the protagonist, Willy is a brilliant but creepy boy who has a talent for influencing his fellows—and not always for the better! In fact, it seems that Willy’s presence has a distinctly negative effect on the school’s teachers and students, whose lives are torn apart by frequent bouts of madness, murder and, in the case of the main character, self-mutilation.

Being the mentally damaged individual he is, the protagonist rarely explains things any more than he has to, leaving us with a lot of seemingly superfluous descriptions and occasional self-contained mini-paragraphs whose meanings are left enigmatic (“I feel like I’m on fire and drowning at the same time. I never felt that way before”). To further complicate matters, toward the end a more learned narrative voice intrudes, presumably that of Willy—who it’s suggested (but never confirmed) may in fact be the true protagonist.

Only a writer of unusual talent and discipline could create such an assured and impressive novel from the disjointed recollections of a frankly crazy individual. Yet Robert Dunbar has succeeded in taking seemingly undisciplined and meaningless material and weaving it into a whole that’s unerringly disciplined and meaningful, not to mention complex, eerie and peerlessly disturbing.

And so ends my two-favorite-books-of-2011 listing. Let’s continue with a brief look at the 2011 output of perhaps the most foremost independent publisher in the biz…

PS Publishing

My friends at PS Publishing had some interesting ‘11 publications, starting with THE BROKEN MAN by MICHAEL BYERS. It’s an adroit skewering of Hollywood mores, as well as an astute portrait of Bush-era America. Pretty ambitious, I’d say, for a 64-page story.

My friends at PS Publishing had some interesting ‘11 publications, starting with THE BROKEN MAN by MICHAEL BYERS. It’s an adroit skewering of Hollywood mores, as well as an astute portrait of Bush-era America. Pretty ambitious, I’d say, for a 64-page story.

Gary Rivoli is a filmmaker specializing in slasher flicks. Like so many others in Hollywood, he’s put aside his ideals to concentrate on trashy films he doesn’t like but which make money. This guy is a type extremely common in Hollywood, driven by equal amounts of self-loathing and arrogance (during a Houston sojourn he ponders how “when outside Los Angeles he was reminded how rich and beautiful his friends were and how relatively ugly and poor everyone else was”).

The horrific portion of the book involves Alice White, a creepy monster maker who creates an imposing creature called The Broken Man for Gary’s latest film. The critter terrifies Gary, who comes to believe that Alice is a witch who’s cast a spell on him. Not a bad set-up, but the way in which it works out is less than inspiring. Gary Rivoli himself could have pinpointed what’s wrong with this novella, as by its end I was hoping for the type of exploitation he’d no doubt willingly provide. No such luck!

Also from PS: TRANSPARENT LOVERS by SCOTT NICHOLSON, a minor novella but a fun one  nonetheless.

nonetheless.

It opens with the just-killed P.I. Richard Steele finding himself in an otherworldly waiting room. Ushered into the office of an afterlife social worker, Steele learns he’s a “tweener” who can end up in either Heaven or Hell. He fills out an application to get into Heaven, but reaching “The Bright Place” entails far more than mere paperwork: Steele will have to go back to the Earthly plain and solve his own murder. Steele’s ensuing adventures contain many noir standbys, including a suitably gritty setting, specifically the skuzzy side of Los Angeles; a femme fatale in the form of a hottie named Bailey who has some inside information on Steele’s murder; and a cold-blooded killer, who with Bailey’s assistance murdered Steele and now has Lee in his sights.

Steele’s first person observations are suitably hard-boiled (“I’d discovered God has a great sense of humor, despite being a heartless bastard”) and sprinkled with quite a few jokes, many of them actually funny (“when you have no bones, the chill doesn’t bother you as much”). This is far from the best work of the talented Scott Nicholson, but as fast and witty entertainment the book hits its mark.

My final PS selection is CHRISTMAS WITH THE DEAD by the incomparable JOE R. LANSDALE. Running a quick 29 pages and packed with inventive carnage, it’s precisely the type of thing Mr. Lansdale could likely dash off in his sleep (zombies aren’t exactly an unfamiliar theme in Lansdale’s oeuvre). Yet this novella has a quirky and endearing arc, even if it does feature many over-familiar elements.

My final PS selection is CHRISTMAS WITH THE DEAD by the incomparable JOE R. LANSDALE. Running a quick 29 pages and packed with inventive carnage, it’s precisely the type of thing Mr. Lansdale could likely dash off in his sleep (zombies aren’t exactly an unfamiliar theme in Lansdale’s oeuvre). Yet this novella has a quirky and endearing arc, even if it does feature many over-familiar elements.

It starts with Calvin, a lonely man who’s among the few survivors of a zombie conflagration (an event that’s become so ubiquitous in horror fiction it no longer requires an explanation) that has claimed the lives of his wife and daughter. It’s Christmastime, and Calvin decides he’ll be putting Christmas lights and decorations up on his house, zombies or no. It seems that despite the all the nastiness in Calvin’s life the spirit of Christmas is alive, as proven by the unexpectedly touching finale in which Calvin goes about putting up his hard-won holiday decorations—which have a most interesting effect on the local zombies.

Lansdale is his usual irrepressible self here, dishing out excess gore, raunchy humor and hard-bitten wisdom as only he can. There’s admittedly not a whole lot to this tiny tale, but I say it’s worth the twenty or so minutes it’ll take you to read it.

Let’s turn now to the ‘11 output of one of the genre’s most vital talents, and certainly one of the most prolific…

Michael Louis Calvillo

MICHAEL LOUIS CALVILLO wins this year’s most prolific horror writer award, having published three  books in 2011. First was the splatterific novella BLEED FOR YOU (Delirium Books). It may lack the maturity and intelligence of Calvillo’s previous output (the novels I WILL RISE and AS FATE WOULD HAVE IT, the collection BLOOD & GRISTLE), but as a straightforward exercise in sheer nastiness it more than succeeds.

books in 2011. First was the splatterific novella BLEED FOR YOU (Delirium Books). It may lack the maturity and intelligence of Calvillo’s previous output (the novels I WILL RISE and AS FATE WOULD HAVE IT, the collection BLOOD & GRISTLE), but as a straightforward exercise in sheer nastiness it more than succeeds.

The opening chapters portend dark things to come, with the nerdy teen protagonist Freddy infatuated with the way-hot Emily. She makes the mistake of leading Freddy on, unaware that he’s recently been released from a mental hospital where he was interred for unspecified violent behavior. It’s clear that Freddy still has issues, and his troubled psyche isn’t helped by the fact that he’s writing a term paper on the Hungarian countess Erzsebet Bathory, who murdered hundreds of virgins and bathed in their blood.

I’ll refrain from giving away the remainder of this twisted tale, but will reveal that it contains murder, mutilation, necrophilia and true love (of a sort). It’s drafted in admirably focused and straightforward fashion, and with a good eye for how modern teenagers interact. Readers desiring refinement and sophistication will be left hungry, but those in the mood for a bloody (and I do mean that literally) good time will be sated.

In the same vein was Calvillo’s 7 BRAINS (Burning Effigy). It’s been said the ultimate compliment you can give a horror story is it makes you question its author’s sanity. I’ll confess that was the case with this deeply sick novella, meaning 7 BRAINS is a success.

In the same vein was Calvillo’s 7 BRAINS (Burning Effigy). It’s been said the ultimate compliment you can give a horror story is it makes you question its author’s sanity. I’ll confess that was the case with this deeply sick novella, meaning 7 BRAINS is a success.

It’s not really like anything else, with a decidedly unique tone set by the dedication: “For Michelle (the author’s wife)…I promise I will never eat your brain.” Unfortunately Malcolm, the protagonist of 7 BRAINS, makes no such promise. Not in the opening chapter, at least, when he inexplicably smashes in his wife’s skull and, under the guidance of a foreign accented voice in his head, ravenously devours his beloved’s brain. It turns out the voice belongs to a split-off part of Malcolm’s psyche that’s concerned about him, and mankind in general, losing humanity. To regain Malcolm’s lost humanity his chatty alter ego—who Malcolm christens Einstein because it’s such a know-it-all—demands that Malcolm devour six more brains, each belonging to a person with specific attributes: ambition, innocence, love, honesty, benevolence and anger. Going about this is obviously easier said than done, and, needless to say, involves a LOT of unpleasantness.

Calvillo also gave us DEATH AND DESIRE IN THE AGE OF WOMEN (Morning Star), a bold and  idiosyncratic riff on the concept of female empowerment. The focus is on Victor and Claudia, a happily married couple who like everybody else are irrevocably impacted by a hallucinatory worm that turns up in the head of every woman on Earth. Claudia brutally kills her young son(!) during the worm-instigated uprising while Victor manages to elude the suddenly homicidal females around him–initially at least.

idiosyncratic riff on the concept of female empowerment. The focus is on Victor and Claudia, a happily married couple who like everybody else are irrevocably impacted by a hallucinatory worm that turns up in the head of every woman on Earth. Claudia brutally kills her young son(!) during the worm-instigated uprising while Victor manages to elude the suddenly homicidal females around him–initially at least.

He’s eventually caught and incarcerated while Claudia is put to work in the new worm-dominated world, run by different stratifications of brainwashed women (meaning some gals are more affected by the worm than others). But Claudia longs to see her husband again and for things to go back to the way they were before “Bloody Tuesday.” She arranges a clandestine meeting with Victor, who will have to be broken out of prison; that’s a good thing, as Victor isn’t doing too well behind bars.

To his credit, Calvillo provides little in the way of reassurance: in this novel love does not conquer all and the ending is far from happy. Calvillo sustains the nastiness of the early scenes throughout, and concludes things on a decidedly tangled and unresolved note. The issues explored in DEATH AND DESIRE IN THE AGE OF WOMEN are thorny ones that have vexed mankind for centuries, and are here given a fictional treatment that feels entirely appropriate.

Other Authors/Publishers

I also appreciated THE WOMAN by the great JACK KETCHUM and LUCKY McKEE (Dorchester Publishing). It’s essentially a novelization of the 2011 film of the same name, whose director Lucky McKee is credited as the co-writer of this quintessentially Ketchum-esque novel. It was conceived as a direct sequel to Ketchum’s OFFSPRING, while the same author’s masterpiece THE GIRL NEXT DOOR is reflected in THE WOMAN’S main plot strand, which sees a cannibal woman kidnapped by a psychotic lawyer who shuts her up in the cellar of his house and, together with his cowed family, subjects her to all manner of torture.

I also appreciated THE WOMAN by the great JACK KETCHUM and LUCKY McKEE (Dorchester Publishing). It’s essentially a novelization of the 2011 film of the same name, whose director Lucky McKee is credited as the co-writer of this quintessentially Ketchum-esque novel. It was conceived as a direct sequel to Ketchum’s OFFSPRING, while the same author’s masterpiece THE GIRL NEXT DOOR is reflected in THE WOMAN’S main plot strand, which sees a cannibal woman kidnapped by a psychotic lawyer who shuts her up in the cellar of his house and, together with his cowed family, subjects her to all manner of torture.

For the most part it’s all quite edifying, with Ketchum’s trademarked spare prose, page-turning readability and shocking violence all fully in evidence. The novel, however, could be a bit stronger overall: the characterization of the evil lawyer is a bit one-dimensional, and some of the developments of the climactic sequences—which include the long-belated introduction of a monstrous character and an equally unexpected home visit by an inquisitive teacher–are less than unbelievable.

But once the lawyer and his family meet their joint fate and it seems the novel is over, we get “Cow,” a more-or-less standalone fifty page vignette. Unlike the rest of this third-person narrative, “Cow” is related in the form of diary entries by a snooty playwright with no relation to any of the previous characters. This guy is captured by the cannibal woman, who’s escaped her captivity and moved back to her seaside cave home base. Here the playwright is made to witness the Woman’s talent for killing and gutting people in an impressively concentrated bit of sustained grotesquerie that is in many respects the book’s most memorable portion, and certainly the most gruesome.

An indispensable (though extremely expensive) 2011 volume was the Subterranean Press omnibus DANGEROUS WAYS, featuring three mystery-themed novels by the incomparable science fiction/fantasy specialist JACK VANCE.

Among DANGEROUS WAYS’ contents is 1973’s BAD RONALD. It’s a “hider in the house” tale in the  mold of the 1989 film of the same name and THE PEOPLE UNDER THE STAIRS—as well as the so-so BAD RONALD TV movie adaptation from 1974—but it actually predated them all by several decades, having been initially drafted back in the 1950s.

mold of the 1989 film of the same name and THE PEOPLE UNDER THE STAIRS—as well as the so-so BAD RONALD TV movie adaptation from 1974—but it actually predated them all by several decades, having been initially drafted back in the 1950s.

Ronald is a deeply maladjusted teen living with his aging mother in a California suburb. After raping and accidentally killing a young girl in his neighborhood, Ronald returns home—where he remains for the next several years, as his mother elects to “protect” Ronald by sealing him up in the downstairs bathroom. Unfortunately the old woman dies just as Ronald is starting to get the hang of his new environment; he stays put, spending his days constructing a private fantasy world called Atranta. In the outside world, meanwhile, Ronald’s house is sold and the Woods, a highly conservative family, move in. This brood includes three luscious girls who interest the increasingly horny Ronald to no end.

Vance showed particular daring in electing to tell his story largely from the confined Ronald’s point of view. This was necessary, of course, in conveying the minutiae of Ronald’s private universe, which Vance lays out with all the immersive detail of one of his fantasy sagas. Ultimately, though, BAD RONALD works primarily because its protagonist is so compelling. Ronald may be a murderous psychopath, but he’s also a complex and tragic figure whose exploits always seem worth following, regardless of how dark and/or strange they become.

Uninvited Books, publisher of the above-mentioned WILLY, put out one of the more noteworthy reprints of 2011, T.M. WRIGHT’S LITTLE BOY LOST. It begins with a disappearance that occurs in a shopping mall parking lot in upstate New York, where young Aaron is snatched out of the back seat of his father’s car by what appears to be his stepmother Marie—who herself disappeared a year earlier. As if that weren’t enough, Aaron’s mother was previously murdered by an unknown assailant. The police naturally suspect Aaron’s father Miles was behind the killing and subsequent disappearances, and Aaron’s brother C.J. is grilled at length by a kindly but firm psychiatrist.

Uninvited Books, publisher of the above-mentioned WILLY, put out one of the more noteworthy reprints of 2011, T.M. WRIGHT’S LITTLE BOY LOST. It begins with a disappearance that occurs in a shopping mall parking lot in upstate New York, where young Aaron is snatched out of the back seat of his father’s car by what appears to be his stepmother Marie—who herself disappeared a year earlier. As if that weren’t enough, Aaron’s mother was previously murdered by an unknown assailant. The police naturally suspect Aaron’s father Miles was behind the killing and subsequent disappearances, and Aaron’s brother C.J. is grilled at length by a kindly but firm psychiatrist.

All this is but a setup for the dreamlike horrors to come, as Miles and C.J.’s reality gradually dissolves. They increasingly find themselves in a prehistoric landscape of arcane rituals and sacrifice, populated by shadowy and malevolent figures.

What resonates about this novel are its many quirky details, such as the precocious C.J.’s penchant for blurting out random details about where he’s been and what he’s seen to anyone who will listen. Even more impacting is the vivid yet spectral atmosphere of rural menace; Wright is a master at this sort of thing, and, as is his custom, keeps the explanations to a minimum, with the emphasis on immersive low-key horror.

THE LIFE OF POLYCRATES & OTHER STORIES FOR ANTIQUATED CHILDREN by BRENDAN  CONNELL (Chomu Press) proves that genuinely vital avant-garde fiction is alive and well. Every conceivable type of experimental quirk is evident in this weird and wonderful collection, which represents a terrific sampling of Connell’s peculiar genius.

CONNELL (Chomu Press) proves that genuinely vital avant-garde fiction is alive and well. Every conceivable type of experimental quirk is evident in this weird and wonderful collection, which represents a terrific sampling of Connell’s peculiar genius.

The novella-length “Life of Polycrates” is a fitfully bizarre history of the ancient Greek ruler Polycrates, his achievements and the many eccentric personalities surrounding him. It’s written in the form of a mock history text, complete with copious footnotes. “Brother of the Holy Ghost” is about the 13th Century life of the man who was situated by Dante at the gates of Hell in the Inferno, while “The Life of Captain Gareth Caernarvon” concerns a late-19th Century hunter whose game includes the most dangerous one. Then there’s “The Search for Savino,” concerning a psychotic Symbolist painter, and “Collapsing Claude,” about a man obsessed with a repulsive woman.

Chomu Press is to be commended for giving Connell’s eccentric drafting free reign. I won’t pretend to “understand” this book’s various oddities and enigmas, but do feel it’s a vital work whose puzzles are well worth your time to work out.

MIDNIGHT MOVIE was the premiere novel by filmmaker TOBE HOOPER, written in collaboration with ALAN GOLDSHER (Three Rivers Press). Its RING inspired narrative could admittedly be a bit stronger—and scarier—overall, but the novel is never less than thoroughly readable and inviting, driven by Hooper’s hard-bitten, quintessentially Texan worldview.

MIDNIGHT MOVIE was the premiere novel by filmmaker TOBE HOOPER, written in collaboration with ALAN GOLDSHER (Three Rivers Press). Its RING inspired narrative could admittedly be a bit stronger—and scarier—overall, but the novel is never less than thoroughly readable and inviting, driven by Hooper’s hard-bitten, quintessentially Texan worldview.

Further influences on this novel would appear to be HOUSE OF LEAVES and WORLD WAR Z, evident in its documentary overlay of various documents and interviews, many of them with Hooper himself. As it happens, a no-budget zombie comedy he made as a teenager called DESTINY EXPRESS has been dug up and is set to receive its first screening in decades at a shithole Texas venue called the Cove. Hooper is summoned to introduce the screening by Dude McGee, an obnoxious internet maven who resembles a “low-budget Harry Knowles.” Also along for the ride is Janine, a hot college gal summoned to be the ticket-taker, and quite a few assorted horror geeks.

The screening is marred by violence, but the real horror is what occurs in the following days. In short order, Janine’s ex boyfriend, who was also present at the screening, brutally assaults her, while some other patrons become “meth arsonists.” Clearly, DESTINY EXPRESS has unhinged its viewers, although I’m a little hazy on the details of the movie virus and how it came into being. As a filmmaker Tobe Hooper isn’t exactly known for his storytelling prowess, so I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that this novel is a bit light on narrative clarity. In ghoulish invention and black humor, however, it excels, and the film geek milieu it describes feels accurate.

I normally go out of my way to avoid vampire series novels, which JON F. MERZ’S THE KENSEI (St.  Martin’s Griffin) is, but its premise was simply too wild to resist: a ninja vampire hunting organ traffickers in Japan! The vamp is Lawson, the headliner of several previous novels by Merz (none of which I’ve read). In THE KENSEI Lawson shows himself to be an irrepressibly cynical martial arts enthusiast with a wisecrack for every occasion.

Martin’s Griffin) is, but its premise was simply too wild to resist: a ninja vampire hunting organ traffickers in Japan! The vamp is Lawson, the headliner of several previous novels by Merz (none of which I’ve read). In THE KENSEI Lawson shows himself to be an irrepressibly cynical martial arts enthusiast with a wisecrack for every occasion.

The author, it should be noted, is an actual back belt ninja, having passed the Godan ninja test which Lawson takes twice in these pages. As described here (and seen on YouTube, which contains video footage of Jon Merz’s Godan test), the test consists of dodging a sword swung at one’s back by a grandmaster ninja—as Merz writes in his acknowledgments page, “To Dr. Masaaki Hatusmi…my sincerest and humble thanks for nearly cleaving me in two on that drizzly cold day in February 2003.”

In short, THE KENSEI is fast, fun and informative. It won’t change the world and nor does it intend to, registering as a good read, pure and simple.

BLOODY WAR by TERRY GRIMWOOD (Eibonvale Press) is a quintessentially British apocalyptic nightmare that makes for a strong post-9/11 addition to the English-centric likes of BRAVE NEW WORLD, 1984, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and V FOR VENDETTA in its pitiless vision of a catastrophic war that destroys England (and, it’s implied, much of the rest of the world), a vision that in grit and sheer bleakness far outdoes most every other recent fictional dystopia.

BLOODY WAR by TERRY GRIMWOOD (Eibonvale Press) is a quintessentially British apocalyptic nightmare that makes for a strong post-9/11 addition to the English-centric likes of BRAVE NEW WORLD, 1984, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and V FOR VENDETTA in its pitiless vision of a catastrophic war that destroys England (and, it’s implied, much of the rest of the world), a vision that in grit and sheer bleakness far outdoes most every other recent fictional dystopia.

It tells the story of Pete, a Londoner who finds his comfortable life thrown into turmoil upon learning of a war his country is fighting against a shadowy force known only as the EoD, or Enemies of Democracy. Nobody seems to know much about the EoD except that they apparently want to do everyone in.

If the above sounds downbeat, be advised that it’s merely a warm-up for the bleakness to come. The actions of the corrupt authorities and the shadowy EoD are not at all unconvincing in these days of terror alerts and mass rioting in London (in light of which BLOODY WAR seems far more topical than when it was initially published). So too Pete’s befuddled mental condition: he finds it difficult to properly mourn his loved ones or even think clearly amid the unceasing onslaught of explosions, gunfire, blood, falling debris, severed body parts and dashed hope, all vividly portrayed and anything but comforting.

Now let’s turn to the lone nonfiction publication horror-themed publication I read in 2011. Yes, I only read one nonfiction horror book last year (although in this case the adjective “read,” as you’ll find, isn’t entirely accurate).

Nonfiction

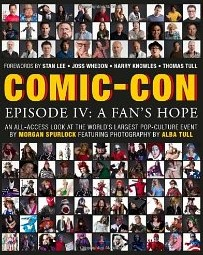

COMIC-CON—EPISODE IV: A FAN’S HOPE was by the pop documentary filmmaker MORGAN  SPURLOCK and photographer ALBA TULL (DK Adult), being a large format coffee-table hardcover about the inimitable pop culture phenom that is the San Diego Comic Con. It’s essentially an adjunct to an upcoming documentary of the same name, which explains why the book is so visually oriented and light on text. In fact, I’d say Tull deserves the lion’s share of credit, as her sprightly and colorful photos comprise at least 80 percent of the book.

SPURLOCK and photographer ALBA TULL (DK Adult), being a large format coffee-table hardcover about the inimitable pop culture phenom that is the San Diego Comic Con. It’s essentially an adjunct to an upcoming documentary of the same name, which explains why the book is so visually oriented and light on text. In fact, I’d say Tull deserves the lion’s share of credit, as her sprightly and colorful photos comprise at least 80 percent of the book.

As a pictorial document of the event this book is quite strong, adroitly capturing the numbing Technicolor swirl of the Con, where costumes of every imaginable stripe are constantly on display. Also pictured are various famous folk—among them Harry Knowles, Kevin Smith, Stan Lee, Eli Roth, Bill Plympton and Spurlock himself—who are quoted on what Comic Con means to them, the consensus being that it allows people to indulge their geekiness in a safe and non-judgmental environment.

This is not the definitive study of this essential event, but a fun book nonetheless!

The following section is something I haven’t done before. It’s in response to criticisms that I give too many favorable reviews. That’s something I’ll readily cop to, but only because when it comes to reading I’m like most everyone else: if a book doesn’t grab me I’m apt to put it down. I’m not exactly lacking in reading material, and don’t see any point in forcing myself to finish a book I know won’t get any better (experience has taught me that if a book doesn’t grab me in its first 3-4 chapters it’s most likely not going to).

As occurs every year, there were several books in 2011 that for whatever reason I was unable to complete. Those titles, and my reasons for abandoning them before their respective ends, follow.

Books I Couldn’t Get Through

THE FIVE by ROBERT McCAMMON (Subterranean Press) isn’t a bad book by any means, and it’s not like I quit reading it in disgust. Rather, I simply put it down and felt no particular compulsion to pick it back up.

THE FIVE by ROBERT McCAMMON (Subterranean Press) isn’t a bad book by any means, and it’s not like I quit reading it in disgust. Rather, I simply put it down and felt no particular compulsion to pick it back up.

Robert McCammon was and is one of the sharpest novelists around, yet THE FIVE’S opening chapters are notably rambling and expansive, detailing the problems faced by a small time rock band. There’s supposed to be a supernatural component but I couldn’t find any evidence of such in those opening chapters, a lapse the McCammon of old would never have let occur.

In 2011 the “unknown classic of the macabre” THE HOLE OF THE PIT by ADRIEN ROSS had its first  standalone publication since 1914, courtesy of Oleander Press. I attempted to read this short novel years ago, when it was republished as part of the Ramsey Campbell anthology UNCANNY BANQUET, and didn’t get very far. I tried again in ‘11 and this time managed to get through four turgidly drafted chapters before quitting—and believe you me, doing so was quite a chore!

standalone publication since 1914, courtesy of Oleander Press. I attempted to read this short novel years ago, when it was republished as part of the Ramsey Campbell anthology UNCANNY BANQUET, and didn’t get very far. I tried again in ‘11 and this time managed to get through four turgidly drafted chapters before quitting—and believe you me, doing so was quite a chore!

TONY BURGESS’ IDAHO WINTER (ECW Press) began promisingly, detailing the life of a tortured individual everyone hates, but around page fifty it got all postmodern, with the protagonist declaring war on his creator and the third person narrator becoming a character in his own right.

The late Dennis Potter could get away with this sort of thing, but with most every other writer I find postmodernism boring and pointless, an abdication of the author’s role as a storyteller to highlight his own cleverness—although in truth I didn’t find Tony Burgess’ postmodern pratfalls in IDAHO WINTER especially clever, just annoying and self-indulgent.

One of the bigger disappointments of the past year was THE SILENT LAND by GRAHAM JOYCE (Doubleday), a novel I was really looking forward to. Joyce is a master of sharp and concise prose, yet THE SILENT LAND’S opening description of a woman trapped in snow is bloated and overwrought in a most un-Joycean manner. That doesn’t make it bad, mind you; as with McCammon’s THE FIVE (see above), I wasn’t especially offended by what I read here. I just wasn’t compelled to read onwards.

One of the bigger disappointments of the past year was THE SILENT LAND by GRAHAM JOYCE (Doubleday), a novel I was really looking forward to. Joyce is a master of sharp and concise prose, yet THE SILENT LAND’S opening description of a woman trapped in snow is bloated and overwrought in a most un-Joycean manner. That doesn’t make it bad, mind you; as with McCammon’s THE FIVE (see above), I wasn’t especially offended by what I read here. I just wasn’t compelled to read onwards.

THE WHITE DEVIL (Harper) is a learned but middling literary horror fest by JUSTIN EVANS, of 2007’s obnoxiously overrated GOOD AND HAPPY CHILD. THE WHITE DEVIL’S setting is a boarding school where one or more ghosts are afoot, which inspires the protagonist to research the life of Lord Byron.

I’m not opposed to highbrow horror, but I do hold such fare to the same standards I do other horror novels—wherein the content must equal if not surpass the form (and the Lord Byron references are kept to a minimum!)—and for me THE WHITE DEVIL, like Justin Evans’ previous novel, had very little to it outside its upscale trappings.