Contrary to what many commentators might have you believe, horror cinema was not “dead” in the nineties. Rather, it was in a transitional mode, marked by innovation and transgression. It was in the nineties, let’s not forget, that David Lynch became a household name and Dell’s Abyss line, which promised “horror unlike anything you’ve ever read before,” came and went. In this atmosphere the serial killer was an ideal horror movie subject precisely because it went against so many hallowed horror traditions.

To be sure, there were a lot of serial killer movies in the 1990s. Those films tended to be reality based, as opposed to the escapist fantasy offered by much of the previous decade’s horror output. There was also the fact that real-life serial killers like Jeffrey Dahmer, Richard Ramirez, Ted Bundy and Charles Manson were headline-grabbers over the previous two decades, and so by 1990 had become firmly implanted in the public consciousness.

The nineties were the time of Generation X (my generation), an overeducated and under motivated bunch who (according to the media, at least) faced life with a disaffected “whatever” attitude. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that the serial killer, marked by skewed morality and a methodology that set him/her apart from the likes of Jason or Freddy, became the unofficial Gen-X horror icon. In addition to movies, Gen-Xers were offered serial killer trading cards, comic books (see the notorious JEFFERY (sic) DAHMER: THE UNAUTHORIZED BIOGRAPHY OF A SERIAL KILLER and its sequel THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF YOUNG JEFFREY DAHMER), specialized T-shirts (who can forget the shirt that had “Dahmer’s” rendered in the iconic style of the Denny’s logo?), Halloween costumes, etc.

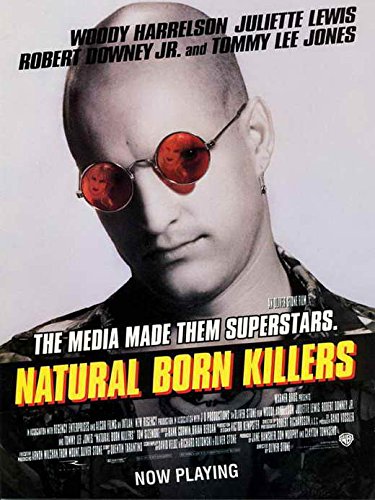

I’m surprised so few films directly exploited the Gen-X-serial killer connection. Of those that did, NATURAL BORN KILLERS was a success, but the Canadian angst-fest LOVE AND HUMAN REMAINS (1993), whose dark comedy and horror-suspense elements (think REALITY BITES crossed with THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS) had the effect of cancelling each other out, was not.

NATURAL BORN KILLERS, released in the summer of 1994, was the ultimate nineties serial killer movie, having begun life as a screenplay by Quentin Tarantino, the quintessential nineties filmmaker. It’s been said that Tarantino initially conceived the script as a retread of BADLANDS (1973), but after viewing Geraldo Rivera’s 1988 televised interview with Charles Manson added a TV-centric arc.

The idea of serial killers as media stars wasn’t new, having been dealt with as far back as the final scenes of the aforementioned BADLANDS (a dramatization of the 1950s-era killing spree of Charles Starkweather), and also John Waters’ comedic SERIAL MOM, released in the Spring of ‘94 (and so beating NBK to the punch by several months), which bluntly spoofed serial killer chic. Yet NBK took that comedy to an outrageous, and quintessentially nineties, extreme by director Oliver Stone. Never one for subtlety, Stone packs the film with lighting and video effects meant to externalize the title characters’ media-addled mind-sets (at one point a slogan is projected on their torsos reading “Too Much TV”), and also an end credits montage of real-life nineties villains like Lorena Bobbitt, Tonya Harding and O.J. Simpson, just in case we didn’t get the point.

Other Tarantino contributions to nineties serial killer cinema include an Associate Producer credit (and uncredited script revision) on the 1991 low budgeter PAST MIDNIGHT (whose dialogue includes the phrase “Natural Born Killer”), and the screenplay of 1995’s FROM DUSK TILL DAWN. The latter film is notable for one of its protagonists, a sociopathic serial killer (played by Tarantino), whose gruesome handiwork is displayed in an early scene that was known to inspire many a walk-out back in ‘95.

The other major nineties serial killer film was Jonathan Demme’s SILENCE OF THE LAMBS, the unacknowledged sequel to Michael Mann’s 1986 MANHUNTER. SILENCE, marked by strong performances and quirky direction that failed to offset the thoroughly implausible B-movie narrative, was a massive hit in early 1991, and swept the Academy Awards. That’s in direct contrast to Mann’s film, which tanked badly.

Like SILENCE, MANHUNTER was an adaptation of a Thomas Harris novel (1981’s RED DRAGON), and remains one of the most stylish and unnerving films of its type. Box office-wise I’d say its biggest problem was simply bad timing: audiences in 1986, weaned on puddle-deep splatter flicks and equally trite sequels to same, simply weren’t prepared for MANUNTER’S harshly realistic, character-based approach.

MANHUNTER marked the screen’s premiere appearance of the deranged psychiatrist Dr. Lector—here rechristened “Lektor” and played, magnificently, by Brian Cox—and also the interviewing-an-incarcerated-killer device that powered THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS. Another 1991 film, the special effects extravaganza BACKDRAFT, used the same device, with Donald Sutherland playing a Lecter/Lektor stand-in who in true SILENCE OF THE LAMBS/MANHUNTER fashion helps that film’s firefighter protagonists track down a pyromaniac.

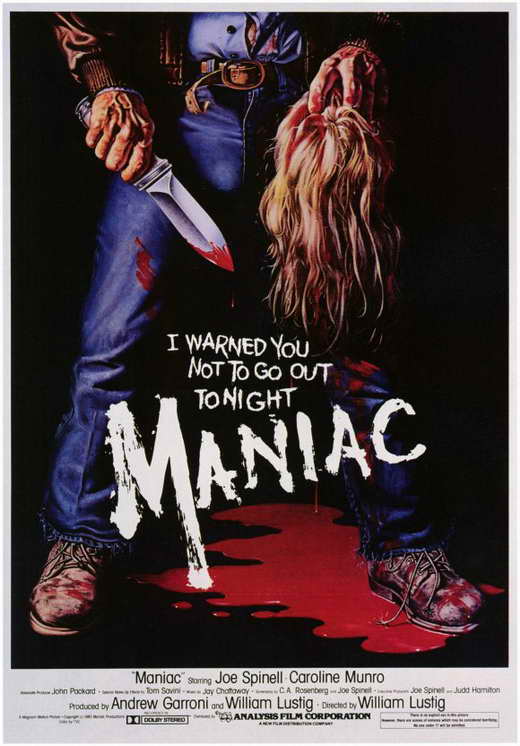

It could be argued that the most fertile period for serial killer cinema was in fact the 1980s. Such films certainly weren’t as prevalent or successful back then as they were in the nineties, but those serial killer flicks that appeared during the Me Decade definitely made an impact. It was then that in addition to MANHUNTER we got MANIAC (1980), a gorefest that stood out from the glut of early 1980s splatter flicks because of its focus on the deranged mindset of its multiple murderer protagonist; the visually innovative Austrian import ANGST (1983), which provided a nerve-shredding minute-by-minute examination of a killing rampage undertaken by a just-released mental patient; CONFESSIONS OF A SERIAL KILLER (1985), which prefigured HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER in its loose dramatization of the crimes of Henry Lee Lucas; the Dutch-made THE VANISHING (SPOORLOOS; 1988), whose spare and methodical narrative concerning a man’s desperate search for his missing girlfriend segued effortlessly into an intense depiction of the doings of a serial killer; and Tony Elwood’s super-8mm gorefest KILLER! (1989), which nowadays plays like HENRY crossed with MANIAC.

It’s hardly insignificant that one of the most iconic nineties serial killer movies, HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER, was in fact completed in 1986—but, fortuitously, wasn’t released until 1990. A similar situation occurred with William Friedkin’s serial killer-themed courtroom drama RAMPAGE, which was completed in 1987 but (due to the dissolution of its distributor DEG) remained undistributed until 1992. Of the two HENRY was the more resonant work, marked by a resolutely frank, nonjudgmental approach to its subject, an outwardly charming sociopath superbly incarnated by Michael Rooker. So upsetting was the film that it was famously given an NC-17 rating by the MPAA for (in an unprecedented decision) “Disturbing Moral Tone.” I doubt audiences of 1986 would have known what to make of HENRY—although they might well have taken to RAMPAGE, which upon its 1992 unveiling played like a TV movie, and not a very good one.

1991’s ROADKILL: THE LAST DAYS OF JOHN MARTIN, a short film (actually a promo reel for a never-made feature) by director Jim Vanbebber, was an impossible-to-forget 14 minute depiction of the sordid reality of a psychopathic killer who putters around a filthy roadside shack amid an unholy mess of blood, entrails and soon-to-be-massacred abductees. The pic may not seem as shocking these days now as it once was, but it broke new ground in sheer ugliness. Another noteworthy Vanbebber effort was THE MANSON FAMILY, a long-in-the-works epic that premiered in 1997, and provided a strikingly psychedelic depiction of the crimes of Charles Manson and his “family” that despite laudable ambitions was done in by a too-low budget.

AMERICA’S DEADLIEST HOME VIDEO, which debuted in 1992, brought a new energy to the serial killer movie format by doing something that at the time was unprecedented: it framed its camcorder shot proceedings as an extended home video made by a young man (Danny Bonaduce) roped into documenting a depraved killing spree. Film Threat’s Chris Gore has been quoted as saying the pic was “so good it’s bound to be stolen by Hollywood.” He wasn’t wrong.

The Belgian MAN BITES DOG (C’EST ARRIVE PRES DE CHEZ VOUS; 1992) actually outdid AMERICA’S DEADLIEST HOME VIDEO in its darkly comedic yet ferocious account of a serial killer whose bloody doings are documented by a too-willing documentary film crew. Other interesting 1990s serial killer dramas from outside the US included the Ukrainian MIRACLE IN THE LAND OF OBLIVION (GOLOS TRAVY; 1992), which juxtaposes a police investigation into a series of killings in a rural village with the second coming of Jesus Christ(!); the Japanese ANGEL DUST (ENJERU DASUTO; 1994), a strikingly stylized depiction of a serial killer who commits a grisly murder in the Tokyo subway system each Monday at 6 pm; the German DEATHMAKER (DER TOTMACHER; 1995), an exercise in dialogue-driven minimalism marked by a superb performance by Gotz George as the infamous child murderer Fritz Haarmann; and SCHRAMM (1993) from NEKROMANTIK’S Jorg Buttgereit, who memorably dramatized the disturbed consciousness of a mass murderer via a flood of demented imagery.

Hong Kong, whose unique brand of action/exploitation cinema was very much in vogue in the nineties, got into the act with DR. LAMB (GOU YEUNG YI SANG; 1992), INSANITY (CHU MU JING XIN; 1993) and THE UNTOLD STORY (BAT SIN FAN DIM: YAN YUK CHA SIU BAU; 1993), all of which more than earned their Category III (adults-only) certifications. The first of those films played like a trashy hybrid of TAXI DRIVER and MANIAC, while the second is a hellaciously over-the-top, though ultimately disposable, home invasion thriller. THE UNTOLD STORY, however, is something else entirely: a fact-based shocker about a deranged restauranteur who finds a novel meat source that has a resonance, bequeathed by the tremendously moving central performance of Anthony Wong, which transcends the sleazy ultra-violence.

The 1992 shot-on-video no-budgeter HELL ON EARTH II: THE ARENA OF DEATH, an attempt at post-apocalyptic sci fi action a la MAD MAX, is significant for the fact that its hero (played by the pic’s co-screenwriter Chip Herman) is a suave serial killer who predated the charismatic mass murderers of NATURAL BORN KILLERS and DEXTER by several years. As for HELL ON EARTH II itself, it plays as you might expect given the non-budget (the film it sequelized was an unreleased short). Also premiering in ‘92 was David Lynch’s poorly received TWIN PEAKS: FIRE WALK WITH ME, which opens with an oblique depiction of the doings of an apparent serial killer, a subplot that comes to an overly abrupt and inconclusive end after about twenty minutes (because, rumor has it, David Bowie, one of the intended leads, couldn’t act).

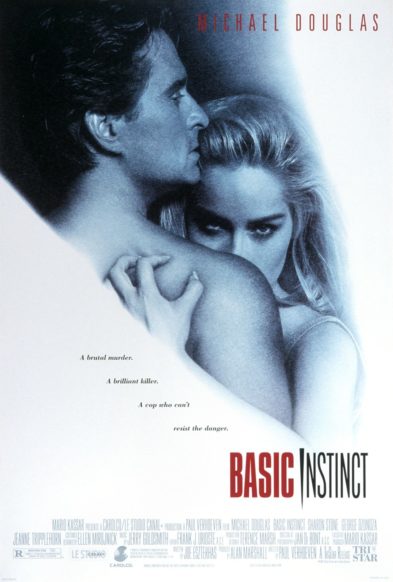

1992’s BASIC INSTINCT was a trailblazer of sorts, though not for its narrative, which was little more than a gender-reversed retread of 1985’s JAGGED EDGE by that film’s overpaid screenwriter Joe Eszterhas. Rather, BASIC INSTINCT’s true worth is in the way it brought the early nineties erotic thriller trope, at the time a staple of grade-B fare like NIGHT EYES, NAKED OBSESSION and LAST CALL, into the mainstream (just as the following year’s JURASSIC PARK did with monster movies), with Sharon Stone in a serial killer-seductress role that seemed better suited to Maria Ford or Shannon Tweed. The formula was repeated in SLIVER (1993), scripted once again by Joe Eszterhas and headlined by Ms. Stone, but to far lesser effect.

If good intentions were enough to make for a quality film 1993’s KALIFORNIA would indeed be the standout so many critics wrongly proclaimed it. The film’s funky, character-driven narrative about a hipster journalist (David Duchovny) visiting the sites of famous serial killings, unaware that one of his travelling companions (Brad Pitt) is himself a serial killer, is laudable for its resolutely gritty, non-sensationalized approach, but director Dominic Sena’s glitzy music video visuals are a constant distraction, as are the performances of Pitt and (as his white trash GF) Juliet Lewis, both of whom overact.

The same year, unfortunately enough, saw the release of the Hollywood-ized remake of THE VANISHING. Directed by the original film’s helmer George Sluizer, this new-and-unimproved VANISHING featured Kiefer Sutherland and Jeff Bridges in a blandly revamped narrative with a tacked-on happy ending. Sluizer’s follow-up was the straight-to-video CRIMETIME (1995), which tried, and failed, to spin a NATURAL BORN KILLERS-ish take on media exploitation via a silly account of an actor (Stephen Baldwin) playing a serial killer on TV, which provides unintended encouragement to the real killer he’s portraying (Pete Postlethwaite).

Another prominent European filmmaker who utilized the serial killer trope in 1993 was Dario Argento, who provided the garroting murderer freak-out TRAUMA. The first of Argento’s films to star his daughter Asia, TRAUMA is not one of his better works, marred by Argento’s unsuccessful attempt at servicing his own inimitable–and quintessentially European—vision while pacifying the American financiers. There are, however, some memorably violent set-pieces, and a sometimes-clever script that was partially credited to the famed horror novelist T.E.D. Klein.

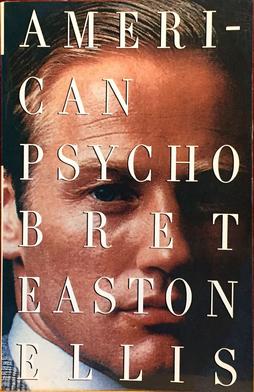

Speaking of horror fiction, it’s a fact that some of the most interesting nineties-era twists on serial killer lore occurred in the literary arena. Examples include Brett Easton Ellis’ notorious exercise in upscale splatter AMERICAN PSYCHO (1991), which was quite iconic, and can be viewed as completing an unholy trinity of early-nineties psychosis together with HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER and THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS. There was also Wayne Allen Sallee’s gritty and surreal THE HOLY TERROR (1992), about a Chicago-based maniac who murders wheelchair-bound homeless men as part of some esoteric, quasi-supernatural ritual; Ramsey Campbell’s gruesomely comic THE COUNT OF ELEVEN (1992), in which a happy-go-lucky Liverpool man embarks on a schizophrenic killing rampage based on numerology and a fateful chain letter; and Garfield Reeves-Stevens’ DARK MATTER (1990), about a lunatic brain surgeon who takes his trade a bit too far. Ellis’ novel was famously adapted for the screen in 2000, but the other three remain unfilmed—although I contend they’d all make promising flicks.

Getting back to the subject at hand, the next significant—and quite possibly final—evolution of serial killer cinema occurred in David Fincher’s SEVEN (1995), which despite a formulaic mismatched-cops-teaming-up-to-investigate-a-series-of-horrific-killings framework had an unpretentious visual dynamism and intensely brooding atmosphere that set it apart from its fellows (it was everything KALIFORNIA wanted to be). Such was SEVEN’s impact that it completely dwarfed Jon Amiel’s COPYCAT, which was released a month after Fincher’s masterwork, and which despite a number of novel touches (such as the fact that its two protagonists were both women) seemed played-out and clichéd.

A similar problem affected many of the decade’s subsequent serial killer flicks, such as Arturo Ripstein’s DEEP CRIMSON (PROFUNDO CARMESI; 1996), a Mexican-made dramatization of the crimes of the 1940s-era Lonely Heart Murders (previously covered in THE HONEYMOON KILLERS) that didn’t feel nearly as fresh or gripping as it might have a decade earlier. The same can be said of the Austrian FUNNY GAMES, which had the misfortune to show up in 1997. By then director Michael Haneke’s creepily protracted depiction of a family tortured by a pair of murderous psychopaths—who frequently break the fourth wall to address the viewer directly and at one point manipulate the reality of the film to benefit themselves—felt pretty tired.

1997 also marked the completion of underground auteur Ari Roussimoff’s Green River Killer biopic TRAIL OF BLOOD, which never got much of a release of any sort. As one of the few who sat through the pic I can attest there’s a definite reason for that! Another fact-based misfire was THE SECRET LIFE: JEFFREY DAHMER (1993), a no-budget Dahmer biopic marked by bad acting and amateurish filmmaking (the 2000 Jeremy Renner headlined DAHMER is a much better film, and it’s not even very good).

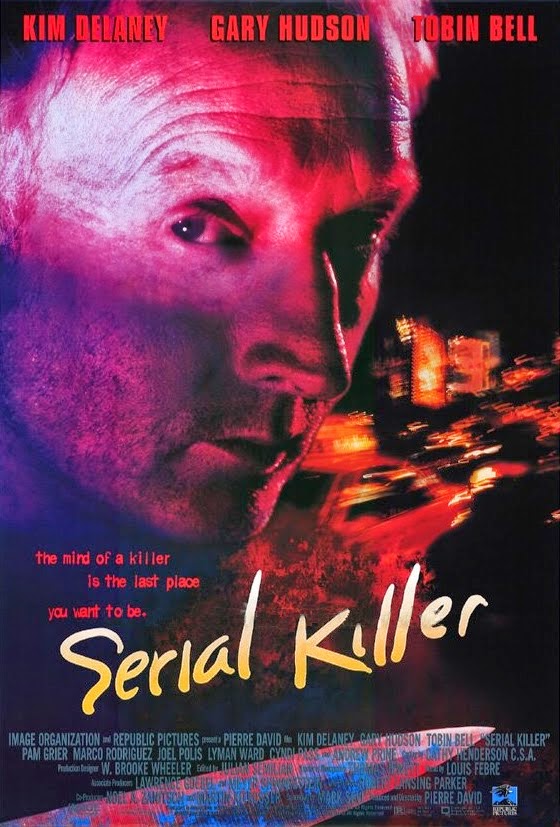

Then there was the straight-to-video SERIAL KILLER (1995), a SILENCE OF THE LAMBS wannabe about an FBI agent (Kim Delany) matching wits with a serial killer, which is notable only for the presence of future SAW headliner Tobin Bell as the killer. The decade’s succeeding years, meanwhile, provided tiresome indie quirk-fests like THE DOOM GENERATION (1996) and CLAY PIGEONS (1998), in which serial killing was made a part of those films’ annoying hip-ironic tapestries.

THE MINUS MAN (1999), the directorial debut of veteran screenwriter Hampton Fancher, was a more sincere effort about an outwardly charming sociopath (Owen Wilson) who likes to poison people, but it once again suffered from a been-there-done-that feel. So too the 1999 Spanish thriller PLENILUNE (FULL MOON), whose ultra-spare filmmaking is mesmerizing, even though the story, about a troubled police inspector stalking a murderer, is nothing that hadn’t already been done several times already.

No wonder a prominent film critic wrote, upon the November 1999 release of Atom Egoyan’s FELICIA’S JOURNEY, which starred the late Bob Hoskins as an especially refined Anglo killer, “What made Atom Egoyan think we needed another serial killer movie?” Never mind that the film is in fact one of Egoyan’s better efforts, a consistently provocative exploration of evil and innocence amid disarmingly scenic Irish locales.

It was a good thing the 1997 Japanese downer CURE didn’t appear (legally) in the Western world until 2001, by which point critics and audiences were able to appreciate the uniqueness of director Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s skilled film, and its hypnotically-inclined mass murderer protagonist. Ditto the French SOMBRE from 1998, which played like an art film remake of HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER, and also the Japanese AUDITION (ODISHON) from 1999, which far outdid BASIC INSTINCT in its depiction of a remorseless female serial killer. Like CURE, SOMBRE and AUDITION didn’t become widely known until after the dawn of the new millennium, and that was to their benefit.

That new millennium has thus far provided some decent entries in the cinema of serial killing, including the Bill Paxton directed FRAILTY from 2001, in which a man (Paxton) enlists his young son to rid the world of demons that are apparently disguised as humans; the Czech NORMAL from 2009, a troubling and compelling depiction of the crimes of the “Vampire of Dusseldorf” Peter Kurten; and, unexpectedly enough, director Michael Haneke’s Americanized remake of FUNNY GAMES, which appeared in 2007 and, in a nearly unprecedented situation, actually improved upon the original film.

It seems we may be at a point in horror’s evolution very much like that of the late 1980s, when traditional scare movie models have lost their luster and innovation is prized above all else. Note the (over)praise lavished upon recent releases like CABIN IN THE WOODS and IT FOLLOWS, acclaim that was predicated largely upon the fact that those films were original, if not exactly precedent-setting. What might the future hold in terms of updated horror icons? We’ll undoubtedly be finding out soon.