Here, in the latest edition of my Year in Bedlam film listings, we leave the nineties behind and enter the eighties, which many claim was the worst decade in cinema history. 1989 would seem to prove that hypothesis, as it was, frankly, an abysmal year for film. 1989’s two major cinematic events—BATMAN, which rewrote the rules for Hollywood blockbusters, and SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE, which did the same for the indie film scene—are now looking so stodgy they might as well have been made in 1949. The year’s best movie release, in fact, was the restored LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, which despite being 27 years old outclassed literally every other movie on the scene.

I will say this for 1989: many of the most iconic (and so not included below) cult films of our time—including BEGOTTEN, MEET THE FEEBLES and PARENTS—hailed from that year, as did the 30 worthwhile obscurities listed below, so things clearly weren’t that bad.

Onto the list…

30. THE UNBELIEVABLE TRUTH

A wistfully nostalgic glimpse back to a more innocent time in American cinema, when movies like this one, an impressive effort in many respects but still very much the work of a first-timer, could actually be released in movie theaters (today, of course, there’s simply no way in Hell this film would ever be shown in any venue outside the festival circuit). Said first-timer is Hal Hartley, who was germinating all his career-long quirks: highly measured dialogue, deadpan comedy, Godardian experimentalism, etc. The narrative involves the late Adrienne Shelly as a rebellious teen obsessed with nuclear war and John Burke as a darkly charismatic ex con who enters Shelly’s suburban community and turns everyone’s lives upside down (not unlike a poverty row SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE). Hartley’s amateur status is painfully apparent throughout, and quite a few scenes fall flat, but the film’s raggedness is an integral part its charm.

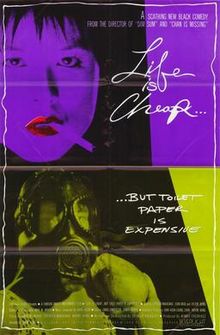

29. LIFE IS CHEAP…BUT TOILET PAPER IS EXPENSIVE

29. LIFE IS CHEAP…BUT TOILET PAPER IS EXPENSIVE

A free-form look at pre-unification Hong Kong via a young hustler’s impressionistic odyssey through that country’s seedy underbelly. This was the first of director Wayne Wang’s quirky faux-documentary takes on his native country, the second being the disappointing CHINESE BOX (1998). This earlier effort is far more interesting, with Wang all-but ignoring his main character in favor of a series of grotesque sketches in which eccentric characters directly address the camera. These folk include a demented butcher (whose mutterings provide the film’s title), an affluent couple excited because they’re slated to be featured on LIFESTYLES OF THE RICH AND FAMOUS, a prostitute and the protagonist’s corrupt boss, who literally serves up a feast of shit on a platter. There’s also a kinetic chase through the streets of HK where the camera literally becomes a character in itself, and a notorious duck-killing sequence that got the film an X rating during its initial US release (the end credits assure us the scene is “pure documentary”).

28. WE’RE NO ANGELS

A remake of the 1950s-era Humphrey Bogart comedy with Robert De Niro and Sean Penn, playing escaped convicts who attempt to pass themselves off as priests in a rural village on the Canadian border. The near-surreal production design of Wolf Kroeger, replicating his legendary work on Robert Altman’s POPEYE, is the best thing about the film. The stars are also good, with Penn being the standout (even though De Niro has the meatier part); even Demi Moore is strong in the thankless female tagalong role. As for David Mamet, who scripted, and Neil Jordan, who directed, both do solid (if unexceptional) work, turning in an absorbing and good looking diversion that may be a bit too brooding for its own good (I think it goes without saying that De Niro, Penn, Mamet and Jordan aren’t exactly the world’s funniest people).

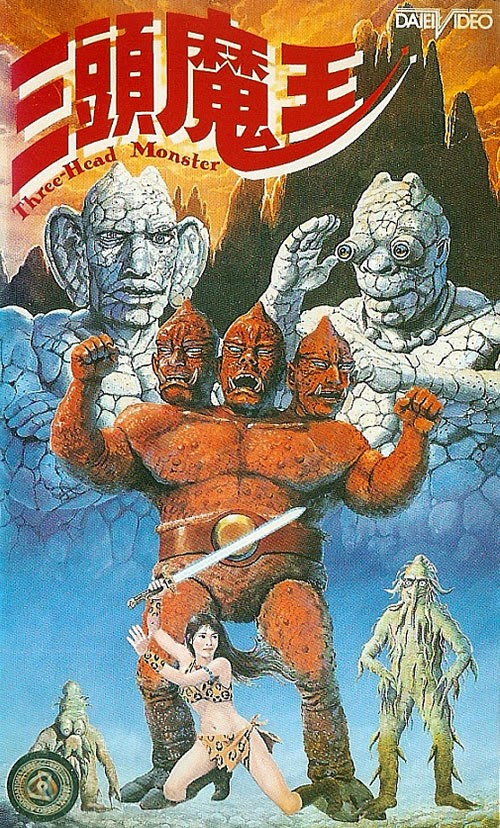

27. GINSENG KING (THREE-HEADED MONSTER)

Crazy Thai stuff that was intended as a straight-faced exercise in fantasy filmmaking—a rip-off of THE NEVERENDING STORY, in fact—but now plays far differently: as a psychedelic spectacle with really bad special effects. It features a kid in search of a kidnapped wood demon called the Ginseng King, an odyssey that entails a procession of bizarrie—a “seig hiel!” spouting Nazi zombie, a giant with a pop-out eye, a warrior babe and a three-headed monstrosity who shoots laser beams (or something). Extremely stupid, as you’d expect, and not a little tacky, but GINSENG KING is as bizarre as nearly anything you’ll see, a cinematic acid trip I feel is well worth taking.

26. A BRITISH PICTURE

An hour-long autobiographical trifle from the late “British Bad Boy” Ken Russell, made for the UK’s SOUTH BANK SHOW and based on his memoir of the same name (retitled ALTERED STATES in the US). Ken’s young son Rupert, wearing a multi-colored afro wig, plays Ken Russell, who’s seen chatting with a journalist (played by Russell’s then wife Vivian), confronting an outraged critic (played by the man himself, wearing an ill-fitting Groucho mask) and frolicking around Ken’s Irish homeland. We’re also shown copious clips from Russell’s films TOMMY, THE RAINBOW and LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM, along with many of his more obscure TV projects. A supremely (and intentionally) dopey exercise that’s pleasing, outrageous and appalling by turns…in other words, exactly what you’d expect from Ken Russell.

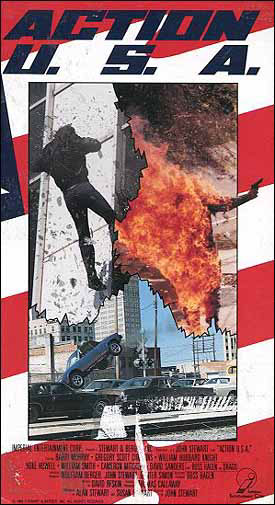

25. ACTION U.S.A.

25. ACTION U.S.A.

That title is appropriate, as grade B action in its purest form is what this micro-epic has to offer. The director John Stewart is, unsurprisingly, a stuntman, and keeps the film flowing smoothly from one testosterone fueled, explosion packed set-piece to the next. About a fetching young woman (Barri Murphy) escorted through Texas by a pair of two-fisted FBI agents (Gregory Scott Cummins and William Hubbard Knight) after her loser boyfriend is killed, the film makes generous use of Murphy’s body in addition to all the pyrotechnics, and features supporting turns by the B-movie veterans William Smith and Cameron Mitchell. Stewart also demonstrates an excellent grasp of tone, keeping things appropriately light-hearted without drowning in the postmodern schmaltz of most of the big Hollywood actioners of ‘89 (LETHAL WEAPON 2, ROAD HOUSE, HARLEM NIGHTS, TANGO & CASH, etc.). Of course the film is extremely lightweight, and contains a lot of dull bits (which occur whenever the action slows down), but it delivers just what it promises.

24. 84 CHARLIE MOPIC

In an intriguing twist on the Vietnam War movie template popular in the late eighties, this film is presented as a faux-documentary made by an Army “Mopic” (for Motion Picture) cameraman stationed in the thick of the ‘Nam. Writer-director Patrick Shane Duncan, an actual ‘Nam vet, does a fine job with this set-up (years before it became popular in the likes of THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT and CLOVERFIELD), creating a real sense of naturalism and immediacy. He’s aided in this by the spot-on cast, who succeed in conveying the comradery and weariness integral to guys in the bush. Of course the film’s low budget rears its ugly head in the near-total absence of anything resembling action in much of the first hour. Things change, though, in the last half hour, when members of the platoon we’ve gotten to know and like inevitably get picked off. Powerful.

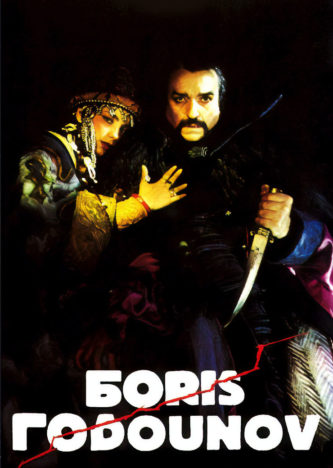

23. BORIS GODOUNOV

One of the more interesting films made by Poland’s late Andrzej Zulawski, and also one of the most obscure. Indeed, BORIS GODOUNOV, about the similarly monikered 16th Century Russian Tsar (Ruggero Raimondi), is very nearly a “lost” film due to the fact that its producers disowned it in the wake of a controversy involving Godounov’s daughter (Kaline Carr), whose onscreen depiction as a wealthy nymphomaniac was offensive to many—resulting in the character being largely excised from the finished film. This would appear to explain, at least in part, the choppy and inconsistent narrative. The film excels, however, as an eye-popping visual spectacle packed with Zulawski’s trademarked excess, expressed here in the highly spastic camerawork, unfettered performances and copious nudity and violence. What really sets it apart is the fact that it was adapted from the opera by Modest Mussorgsky, to which the actors lip-synch the sung dialogue and Zulawski provides a strikingly expansive, full-bodied visualization. Also noteworthy is the artifice to which Zulawski subjects the film, which begins onstage in an opera house and segues into actual locations (while frequently cutting back to the stage), making no attempt to hide the plainly visible lighting and camera equipment, nor the gaudily painted scenery (with red and purple tones predominating). The result is a magnificently odd and eccentric spectacle that’s not quite all it could be, but satisfies nonetheless.

22. SPEAKING PARTS

This was the film that turned me on to Atom Egoyan back in ‘89, and it remains a stylish and invigorating piece of work. Featured are a bunch of nutty Canadians looking to connect with one another, but finding their only real means of communication to be through TV screens (TV was a major obsession of Egoyan’s early films); all the characters are related in some way or other, but the connections don’t make themselves apparent until the last ten or so minutes. As in many of Egoyan’s early films, this has the effect of turning what should be a provocative psychological study into an icy intellectual puzzle (something he’s remedied in his more recent work), but there’s still much to admire, including a powerfully creepy atmosphere, a diverting virtual masturbation session and a superbly edited climactic montage. BTW, the editor in question was Bruce MacDonald, who would go on to direct great films like DANCE ME OUTSIDE and HARD CORE LOGO.

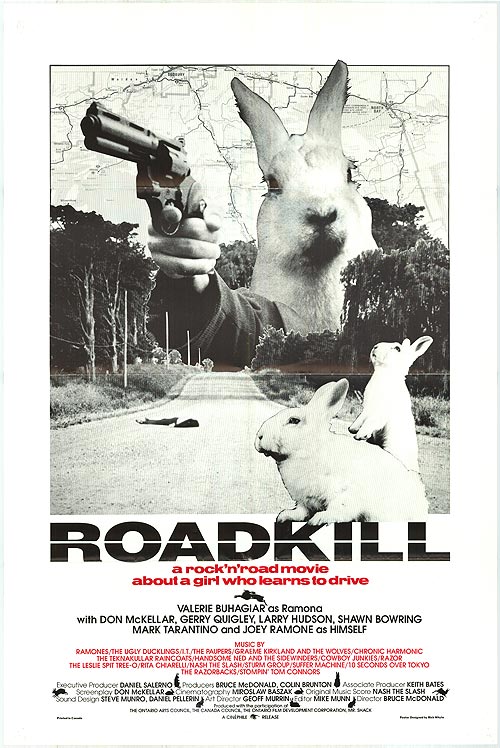

21. ROADKILL

21. ROADKILL

Speaking of Bruce MacDonald, here’s his little known directorial debut. Shot in black and white on a VERY low budget, ROADKILL starts off slowly but, like all of McDonald’s best films, steadily ingratiates itself with the viewer. Valerie Buhagiar stars as a young woman hired by a disgruntled rock promoter to track down and fire a renegade band. Hitting the back roads of Canada, she encounters many colorful folk, including Bruce D. himself as a documentary filmmaker and Don McKellar (also the film’s screenwriter) as an aspiring serial killer. The rock ‘n’ roll infused score is great throughout and McDonald, even at this early stage, proved he had a sure grasp of character and a terrifically funny/anarchic sensibility.

20. LADY TERMINATOR (PEMBALASAN RATU PANTAI SELATAN)

One seriously stupid film, an Indonesian TERMINATOR rip-off that was revamped for the US video market, complete with hilarious English dubbing and eighties muzak—in short, the very definition of a “So bad it’s good” movie. It starts out 100 years ago, with a princess raped by an enchanted serpent who settles inside her you-know-what, but when a too-insistent lover removes the snake she places a curse on the stud’s future offspring. Cut to 100 years later, as the guy’s daughter gets possessed and embarks on a rape and killing spree, which consists of a number of heavily edited sex scenes (I’d love to see the original version) and large-scale shootouts lifted directly from THE TERMINATOR. Best of all is the end, where the “Lady Terminator” gets fried in an explosion, yet gets back up and shoots laser beams from her eyes!

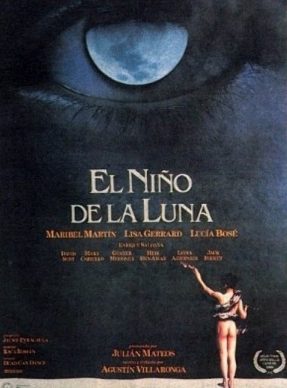

21. MOON CHILD (EL NINO DE LA LUNA)

Spain’s Agustí Villaronga followed up his fearsome 1986 masterpiece IN A GLASS CAGE with this highly ambitious mystical fantasy. The setting is Spain in the 1920s or 30s, where a young orphan boy is being kept in a compound run by a shadowy occult organization. The organization’s heads set up a young woman to be impregnated with the “son of the moon” in a bizarre nocturnal coupling that takes place on a moonlit platform. The boy and the woman decide to flee the compound, stowing away on a cargo ship to Africa, where their destiny awaits. From a purely visual standpoint this film is a masterpiece, with a nightmarish beauty that would make David Lynch proud and some ingeniously modulated Hitchockian suspense. Equally impressive is the highly percussive Dead Can Dance score, which ranks among the most eerie and haunting of the decade. There are also some fine performances, with seventies hottie Maribel Martin (of THE BLOOD-SPATTERED BRIDE and A BELL FROM HELL) being the surprise standout in a strikingly layered and emotional turn. Where Villaronga goes wrong is in his consistently implausible and under baked narrative. That doesn’t render the film any less striking, but does prevent it from reaching its full potential.

18. BLACKEYES

Another fascinating, elliptical and quite brilliant exercise in brain-fried melodrama from Dennis Potter, England’s greatest TV scripter. A BBC miniseries, BLACKEYES was based on Potter’s own novel of the same name. Critics excoriated it, unable to get over the fact that the story of a lecherous middle aged writer’s unhealthy obsession with a beautiful young woman was clearly based on Potter’s own proclivities. The whole point of the enterprise is show how male writers and filmmakers objectify woman—and how the woman herein decides to change that. Potter’s interest in the title character is made clear by the narration, which is spoken by Potter himself; in the course of the story said narrator freely admits to desiring the luscious Blackeyes, and increasingly involves himself directly with his onscreen creations. There’s also a middle aged author writing a novel about an old man and his young niece, who provides the inspiration for Blackeyes. As you might have guessed, this an extremely complex, multi-faceted creation that freely juggles numerous levels of “reality.” It’s frequently confusing and at times downright frustrating, but quite compelling in its own way, with colorful and audacious direction by Potter himself (who took over from the original helmer Nicolas Roeg). The acting is solid, with Gina Bellman as Blackeyes doing a credible job of lounging around in various stages of undress and looking sexy (not exactly a demanding role, but a memorable one nonetheless).

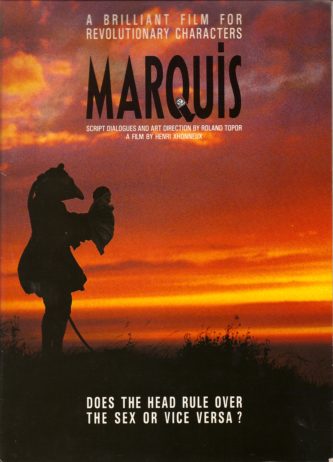

17. MARQUIS

17. MARQUIS

This nutty French reverie ranks with messed-up classics like FORBIDDEN ZONE and MEET THE FEEBLES. The title refers to the one and only Marquis De Sade, who (as in other De Sade biopics like MARAT/SADE and QUILLS) spends the movie imprisoned, where he’s subject to the whims of a number of corrupt folks in addition to his own unchecked libido. The film’s most bizarre conceit is that all its characters are costumed as different animals, with the Divine Marquis outfitted as a dog, his guard a rat and the prison governor a rooster. The narrative involves a plot by the higher-ups to frame the Marquis for a rape, but the real action occurs in the Marquis’ contradictory relationship with his talking penis, an extremely chatty and insistent little guy who’s always wanting to be fucking something, be it a hot chippie or a crack in a wall. Conceived and designed by the famed satirist Roland Topor, MARQUIS also features Claymation segments illustrating the main character’s demented psychosexual fantasies, as well as much lascivious behavior from a bevy of sadomasochistic perverts.

16. TALVISOTA (THE WINTER WAR)

This Finnish WWII drama exists in several different versions: a 3½ hour director’s cut, a theatrical cut that runs a little over two hours and (the crown jewel in my view) a five part miniseries version that runs 275 minutes. All three cuts have the same attributes, namely a superbly magisterial and realistic depiction of the 1939 Soviet invasion of Finland, as seen through the eyes of a Finnish platoon charged with erecting defenses against the oncoming Russians and then holding them back once the attack begins. The battle scenes are among the finest I’ve seen in any movie, being suitably gritty and bloody, and enhanced by a wealth of telling detail of a type that isn’t usually included in war movies—such as the minutia of wartime mail delivery and the methodology of transporting soldiers to the front lines (which in this case involves a bus). Conventional heroism has no place in this film’s fatalistic universe, as we learn in one scene in which an overenthusiastic soldier disobeys orders and confronts the enemy directly, only to get unceremoniously mowed down. The film is not without some overriding flaws, most of them character-related; none of the many men and women to which we’re introduced are particularly unique or interesting individuals, and there are no real standout performances. The film’s brilliance is in its panoramic scope, which, needless to say, works much better as a whole rather than the sum of its parts.

15. MEET THE HOLLOWHEADS

A sci fi-tinged sitcom parody set in some bizarre alternate universe that’s equal parts Tim Burton and Terry Gilliam. In this place a “typical” family, aptly monikered the Hollowheads (whose ranks include John Glover and Juliette Lewis), live in a big house governed by slimy ducts and creatures that suck wounds off people’s faces. There are also large fleas used by the kids in their indescribable board games, “Grandpa” who lives in the basement and has to have his food administered through a mammoth syringe, and a giant eyeball that watches over everything. There isn’t much depth, with the key element being the matter-of-factness with which the filmmakers and their cast treat all this weirdness…not to mention some astonishing special effects that were somehow achieved on a very tight budget. It may not be ALPHAVILLE, but this is one science fiction comedy that’s much ballsier than most.

14. KINGSGATE

Another quirky no-budgeter from the Vancouver-based painter/writer/filmmaker Jack Darcus, following up his similarly scrappy features DESERTERS and OVERNIGHT. Alan Scarfe (who headlined DESERTERS) and his real-life spouse Barbara March spearhead this profoundly dark comedy inspired, reportedly, by an altercation between Darcus and Scarfe that occurred at the latter’s vacation home. This explains the bitterness and disillusionment that suffuse the film, about a wimpy middle aged teacher (Duncan Fraser) whose relationship with a much younger pupil (Roberta Maxwell) unravels after they visit first her parents (one of them played by Christopher Plummer) and then his famous writer pal Kingsgate (Scarfe) and his wife (March). The couplings in all cases are falling apart, proving Kingsgate’s oft-repeated claim that “relationships are a duel to the death!” This is a distractingly low budget film, yes, but it provides an intelligent look at contemporary relationship woes with a refreshing absence of the moralistic underpinnings found in similarly-themed stateside fare (such as HUSBANDS AND WIVES and YOUR FRIENDS & NEIGHBORS).

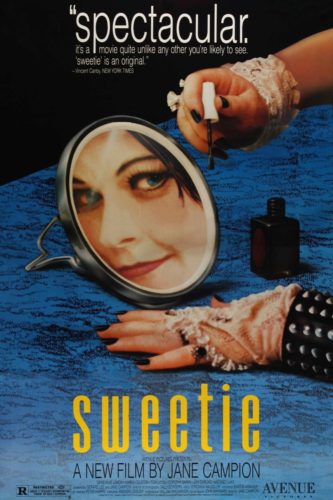

13. SWEETIE

13. SWEETIE

A totally original, defiantly subversive Australian import. Kay (Karen Colston) is an extremely repressed young woman living in non-harmony with her boyfriend, until her estranged sister, a fat and obnoxious bitch known as “Sweetie” (Genevieve Lemon) shows up one day. Sweetie is the exact opposite of her sister, seeming like an eruption from Kay’s fractured psyche; Sweetie pukes, farts, pisses on the ground and is given to odd proclivities like painting herself purple. Kay and her family want nothing to do with Sweetie, but like a force of nature she keeps turning back up, accentuating the fact that Kay and co. are all just as grotesque in their own way. This was the film that put Jane Campion, whose debut feature this was, on the map, although it caused a minor scandal at Cannes. It’s a difficult and off-putting (intentionally so) viewing experience, but in the manner of masterworks like FREAKS or BLUE VELVET—many critics didn’t understand those movies when they were first released, and they didn’t get SWEETIE either. Maybe this is why Campion has spent much of the rest of her career turning out comparatively wimpy award-baiting fare like AN ANGEL AT MY TABLE and THE PIANO.

12. BEYOND DREAM’S DOOR

Astoundingly tripped-out eighties horror that nowadays plays like a no-budget variant on David Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE. It is perhaps the ultimate dreams-within-dreams movie, with a college student haunted by nightmares involving a giant toothy monster. It gets so bad the poor guy can’t tell where the dreams end and reality begins, and somehow draws a psychology professor and his pretty young assistant into an irrational universe characterized by zombies, a creepy kid with bugged-out eyes, books that turn into snapping critters, dinosaur teeth that appear and vanish without any discernible reason, a zombie girl with her head blown off, etc. I was annoyed at first by the inconsistencies in the film stock, stilted performances and tacky synthesizer music, but as the film went on those concerns largely melted away. BDD is an authentically dreamlike product that despite its apparently free-form construction has an overriding logic that compels interest—and all-but demands repeat viewings. It’s also colorful and fast paced, with a minimum of chatter and plenty of striking budget-lite special effects.

11. CHAMELEON STREET

One of the great unknown independent films of the eighties, and certainly the one of finest-ever examples of “black” cinema. CAMELEON STREET is based on the true story of William D. Street, a black ex-con who scammed his way into several professions through his talent for imitation, “working” as a surgeon, lawyer and social worker. This low budget movie tells his story in unforgettably funky, innovative fashion, with the writer and director Wendell B. Harris Jr. playing Street. Harris’ deep voice is a marvel, but his filmmaking savvy is even more striking. He’s created a revolutionary piece of cinema that ranks with the new wave films of the sixties in freshness and innovation, with moments of laugh-out-loud hilarity and nail-biting suspense—especially during an excruciating scene in which Street, in faux-doctor mode, bullshits his way through an operation.

10. BAXTER

Baxter is an evil dog whose thoughts are voiced on the soundtrack. This French import, adapted from Ken Greenhall’s English language outrage HELL HOUND, is told from Baxter’s point of view as he’s released from a pound and passed from owner to owner. Those owners include an old lady with whom he grows tired and drowns, a young couple who dump him after he tries to off their baby, and finally a severely disturbed Hitler-obsessed kid who’s every bit as evil as Baxter. Naturally Baxter loves the kid, who abuses him (in some unsettlingly realistic scenes—there were clearly no ASPCA representatives on this set) and forces him to obey at all costs…until Baxter goes against his master’s bidding, leading to a profoundly upsetting finale. Strong stuff, somewhat crudely made and containing a number of dead spots (which occur nearly any time the humans take center stage), but still mandatory viewing for all weird movie buffs.

9. JESUS OF MONTREAL (JESUS DE MONTREAL)

9. JESUS OF MONTREAL (JESUS DE MONTREAL)

French-Canadian filmmaker Denys Arcand followed up his 1986 triumph THE DECLINE OF THE AMERICAN EMPIRE with this very eccentric dramedy. Here Arcand takes on Christianity in a supremely imaginative story about a rag-tag troop of actors putting on an avant-garde theater piece based on the crucifixion. This causes all sorts of problems with church authorities and the media, coupled with the fact that the lead actor (Lothaire Bluteau) begins taking his role—as Jesus Christ—a bit too seriously. The result is a fascinating and consistently absorbing film, albeit one that’s also notably overlong and self-indulgent—the inevitable consequences, it seems, of such a unique and ambitious piece of work.

8. ELEPHANT

A profoundly innovative, shattering and disturbing 37-minute film made for British television by the late Alan Clarke. Lensed in Northern Ireland during “The Troubles,” it consists entirely of a succession of shootings. No motives political or otherwise are given for the murders, and there is virtually no dialogue—just long tracking shots through fields, deserted alleys, nighttime gas stations, dark corridors, etc. Sometimes we follow a gunman up to the killing and at others the killers appear out of nowhere. Each shooting, in any event, concludes with a lengthy shot of the victim lying on the ground in stark and unglamorous fashion. Those looking for answers to Northern Ireland’s problems won’t find them here, but Clarke’s point seems to be that there are no answers to had, easy or otherwise, yet ignoring the unrest plaguing the country was an unacceptable solution. Then again, a large part of the film’s effectiveness is in the non-specific mundanity of its settings; it could be taking place just about anywhere, which, again, seems a calculated decision on the part of the filmmaker.

7. THE FIRM

Another blistering drama from the brilliant Alan Clarke, made (like ELEPHANT) for the BBC. A pre-sellout Gary Oldman gives one of his finest-ever performances as a 30-year old working class psycho who, when not attempting a normal existence with his wife and infant daughter, likes to hit the town with his football hooligan friends for a bit o’ the old ultraviolence. The relentless brutality and atmosphere of total devastation make for a blistering yet exhilarating film that puts the viewer in essentially the same mindset of Oldman and his pals; we may not like or condone the violence, but it’s impossible not to be carried away by it. My only problem: the cockney accents are so thick I often couldn’t understand a goddamn thing!

6. VISITOR OF A MUSEUM (POSETITEL MUZEYA)

This was Russian filmmaker Konstantine Lopushansky’s similarly themed follow-up to his masterful LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN (1986), and it’s nearly as brilliant. VISITOR OF A MUSEUM is certainly ambitious, depicting a fully realized post-apocalyptic milieu in which mountains of scattered debris dot the landscape in the every direction and the populace consists largely of freaks and mutants. The protagonist is a young man who arrives at a burned-out beachfront hotel in search of a museum submerged beneath the waves. Much of the film’s first half consists of an extremely contemplative sequence of events that show Lopushanksy’s debt to his mentor Andrei Tarkovsky (that Lopushansky worked as a production assistant on STALKER is evident throughout). The second half is something else entirely: a hallucinatory Christ parable that has the protagonist becoming an unwitting savior to a vast congregation of freaks. He drifts into an increasingly psychotic reality, ending up a babbling recluse crying out to an unseen deity who offers little in the way of response. This proceedings are profoundly bleak, yes, and somewhat less than subtle in their overbearing Christian symbolism, but they also demonstrate a visual grandeur that places Lopushansky in the front ranks of Russian filmmakers. I don’t know what the budget was, but it looks to have been substantial, with insanely extravagant art direction and wide shots in which nature itself—in the form of lightning, crashing waves and the sun emerging from behind clouds—appears fully complaint with the director’s vision.

5. A TV DANTE: THE INFERNO–CANTOS I-VIII

5. A TV DANTE: THE INFERNO–CANTOS I-VIII

A positively mind-expanding piece of video making, co-directed by England’s brilliant, idiosyncratic Peter Greenaway. It may well be the most accomplished shot-on-video production ever, fully utilizing the medium’s many strengths. It helps, certainly, that the source material is Dante’s INFERNO, the legendary literary jaunt through the nine levels of Hell. Greenaway and co-director Tom Phillips provide a literal rendition of the inferno’s horrors, along with a sub textual thesis on Dante’s background. The resulting video funhouse is a wonder to behold, with countless multi-layered, digitally manipulated images competing for our attention in an expressionistic masterpiece that’s by turns darkly comical, repellant, educational, ambiguous and never boring.

4. SANTA SANGRE

A prime dose of Alejandro Jodorowsky madness. Rebounding after the disastrous TUSK (1980), Jodorowsky, one of the cinema’s true gods IMO, created an unspeakably whacked-out murder mystery that plays like THE HOLY MOUNTAIN crossed with PSYCHO. It begins with a kid witnessing his father slash his mother’s arms off and then take his own life. The brat grows up in an insane asylum until his mother, still armless, shows up one day and helps him escape. That’s only the half-way point; from then on the guy and his mother start up a novelty act, with him using his hands and arms in place of hers. Meanwhile, a number of murders are occurring around the area—might our “hero” have anything to do with them? Only Jodorowsky could have conceived a story this ingeniously twisted, and he includes all his trademarked surreal touches (detachable ears, elephants with nosebleeds, pythons erupting from crotches, etc.). But there’s also a core of real sadness and regret (this is one of the few films I’ve seen recently that actually brought tears to my eyes), and an authentically redemptive finale.

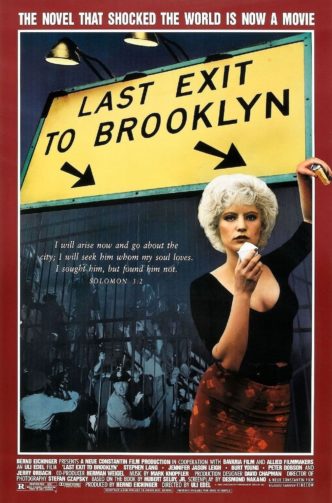

3. LAST EXIT TO BROOKLYN

Hubert Selby Jr.’s 1964 LAST EXIT TO BROOKLYN is one of the finest and most controversial novels ever written. This long delayed adaptation follows the text fairly closely, but employs a style all its own. It isn’t quite Selby (whose volcanic prose would be impossible to translate to any other medium), but the film works superbly on its own terms. German director Uli Edel (CHRISTIANE F.) has aped to perfection the style of a 1940s Hollywood melodrama, but with a heady dose of 90’s sex and violence. The book’s hellish urban setting and myriad of unforgettable characters—Harry Black the repressed homosexual, Georgette the love-sick drag queen, Tralala the prostitute—are brought to life with eye-popping vividness. Indeed, it’s in the casting that the film really cashes in on Selby’s vision, particularly in the late Alexis Arquette’s take on Georgette and (especially) Jennifer Jason Leigh’s extraordinary personification of Tralala, who’s exactly as I always pictured her: a sexy but childlike and naive young woman who, like all the characters, is in far over her head.

2. RED AND ROSY

One of my all-time favorite shorts, the black and white RED AND ROSY is the profoundly hallucinatory account of Big Red Friedman, a drag racing king who’s critically wounded in a horrific accident. After a botched operation he becomes addicted to adrenaline, and so builds a drag racing simulator that pumps the stuff directly into his body. He hooks up with Rose, a drag racing groupie, and they descend into adrenaline addiction, ending up as Survival Research Laboratory–created, Robert Williams-influenced monsters. The film is an incredible multi-media sensory assault, mixing documentary drag racing footage, animation and mind-tugging Lynchian dream sequences. Apparently director Frank (LOVE GOD) Grow shot enough footage for a feature length narrative, but compressed it into a brain-melting 18 minutes. Grow’s love of drag racing is evident throughout, resulting in a gruesome, kinetic and irresistible ode to the sport that remains a groundbreaking and unprecedented accomplishment.

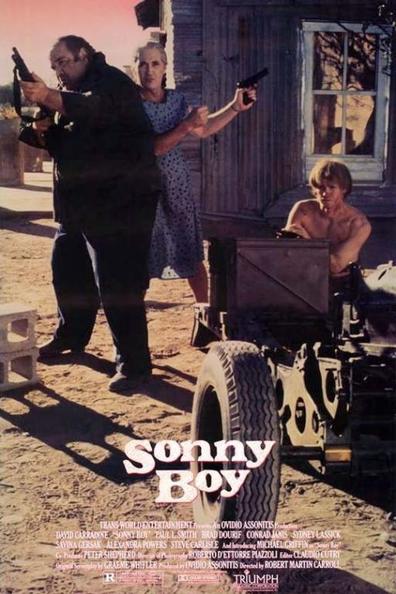

1. SONNY BOY

1. SONNY BOY

This SHOULD have been the cult film of the eighties, a decade filled with independent films hyped (for the most part misleadingly) as “shocking”, “subversive”, “controversial”, etc. SONNY BOY really is all those things, an unabashedly bizarre indie that got lost in the shuffle but deserves—nay, demands—a reappraisal. It’s got David Carradine in drag (which none of the other characters ever comment upon) and Paul Smith as his psychotic husband who runs a desert crime ring. When Smith’s partner in crime Brad Dourif steals a car containing a baby boy, Smith and Carradine decide to raise the kid in their own special way: they torture and abuse him unmercifully, creating a seemingly remorseless killer who does Smith’s dirty work for him. But eventually Sonny Boy escapes his confines and rampages through the surrounding town, leading to a massive confrontation involving cars, motorcycles, cannon fire and lots of explosions. There’s never been another film like this one; tonally it falls somewhere between PARIS, TEXAS and PINK FLAMINGOS, with artfully composed widescreen visuals in service of a profoundly demented narrative. Of course, this micro-budgeted film is also crude as Hell, but the material is funky enough in style and attitude that the crudities actually works to its advantage—indeed, without them I believe SONNY BOY would be far less memorable than it is.