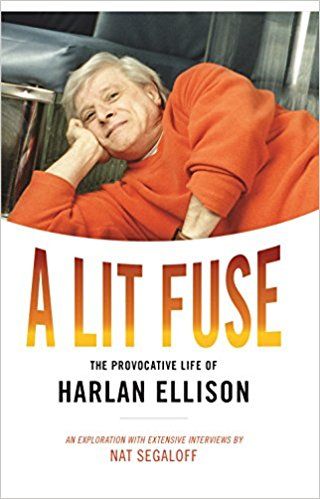

By NAT SEGALOFF (NESFA Press; 2017)

By NAT SEGALOFF (NESFA Press; 2017)

An excellent book about an individual who really should need no introduction. If you’re a horror/fantasy/science fiction buff you’re probably familiar with at least some of the writings of Harlan Ellison, which include books like I HAVE NO MOUTH AND I MUST SCREAM, THE GLASS TEAT and MEFISTO IN ONYX, and innumerable stories, essays, lectures, etc. I’m sure you’re also familiar with the equally innumerable stories about him, which are as outlandish as his fiction. Harlan stories, true and false, have been circulating—of how he allegedly threw a fan down an elevator shaft, mailed a dead gopher to a publisher, publicly groped author Connie Willis, etc.—for seemingly eons.

Author Nat Segaloff is up to the task of chronicling this whirlwind life. Segaloff’s other books, after all, include HURRICANE BILLY, a 1990 biography of director William Friedkin, a man nearly as volatile as Ellison (Ellison and Friedkin once met and, according to this book, didn’t hit it off, being too much alike). Obviously Segaloff isn’t afraid of controversy, although he’s stymied by the fact that much of the information here comes from direct interviews with Ellison—who, as Segaloff admits early on, is rarely truthful about his exploits. This explains why, for instance, Segaloff is forced to acknowledge that multiple versions of the abovementioned throwing-a-fan-down-an-elevator-shaft story exist outside the one provided by Ellison.

Segaloff does a good job tracing Ellison’s outrages, which began during his childhood in Painsville, OH in the late 1930s and 40s. About those years Ellison admits “I was a nuisance, I was a pain in the ass, I was a real fuckin’ nightmare.” That period was further marked by his father’s untimely death when Ellison was a teenager and a rift with his sister Beverly (which lasted until her 2010 demise).

From there Ellison worked a variety of odd jobs before finding his calling as a writer, primarily in the print and television mediums. Along the way he made a lot of enemies (such as the late Forrest J. Ackerman, who Ellison dubs “a piece of shit”) with his naturally combative, egomaniacal personality, and married no less than five times. His latest marriage, to one Susan Toth, has somehow lasted an amazing thirty-plus years, something that evidently surprises Ellison himself.

As any sympathetic Ellison biographer inevitably must, Segaloff functions more often than as an apologist for his subject. Innumerable excuses are made for Ellison’s behavior, such the abovementioned Connie Willis groping, which Segaloff suggests may not have actually occurred; a BLOW UP-worthy analysis of a video recording is provided to reinforce the point (“Enlargement of the frames shows that only Ellison’s fingertips make contact with Willis’s chartreuse satin dress; there is no apparent squeezing”). Segaloff is also careful to include an upbeat quote by the late Ed Bryant in the chapter about the LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS fiasco—referring to a massive Ellison-edited anthology that was supposed to be published back in the 1970s but has yet to appear–claiming “as long as there is any possibility of THE LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS in whatever form coming out, I…am leaving my story on submission as I promised him forty years ago.”

But Segaloff doesn’t shy away from his subject’s darker side. Examples of such range from the abovementioned mailing-a-dead-rodent-to-a-publisher account (which occurred after Ellison had threatened to kill said publisher’s children) to demanding Denis Kitchen of Kitchen Sink Press put Ellison on his comp list and then bitching that the free stuff he received wasn’t top quality. Segaloff himself admits to having been the target of Ellison’s ire, receiving a hateful letter and a parchment reading “The Harlan Ellison First Warning Notice—Do Not Do It Again” for the crime of sending a birthday card.

The book ends on a sad note, with Ellison felled by a debilitating 2014 stroke that’s left him unable to write and severely limited his ability to move around his house. I may be projecting, but I detect a hint of glee in the climactic line “For years he had fought the entire world. Now he was fighting himself.”