This 1992 Japanese production is that rarity of rarities: a successful attempt at reimagining a classic story. That story is Mary Shelly’s FRANKENSTEIN, to which THE LAST FRANKENSTEIN adds an apocalyptic setting, and addresses a number of questions modern readers might have about the text. What might Frankenstein’s Monster’s sex life be like? Does the creature watch TV? Go to the beach? LAST FRANKENSTEIN answers all those queries, but it works, ultimately, not because of its similarities with Shelley’s story, but for its dissimilarities and departures—from Shelly and just about everything else.

This 1992 Japanese production is that rarity of rarities: a successful attempt at reimagining a classic story. That story is Mary Shelly’s FRANKENSTEIN, to which THE LAST FRANKENSTEIN adds an apocalyptic setting, and addresses a number of questions modern readers might have about the text. What might Frankenstein’s Monster’s sex life be like? Does the creature watch TV? Go to the beach? LAST FRANKENSTEIN answers all those queries, but it works, ultimately, not because of its similarities with Shelley’s story, but for its dissimilarities and departures—from Shelly and just about everything else.

Writer/director Takeshi Kawamura is a leading Japanese avant-garde playwright, and THE LAST FRANKENSTEIN started out as one of Kawamura’s theater pieces. It retains much of its theatrical origin, mostly in the staging and casting departments (many of the actors are culled directly from the Tokyo theater world). So far it’s Kawamura’s only filmmaking credit.

The tale centers on Sadusawa, a science professor at a small school on the outskirts of Tokyo. He lives with his telekinetic daughter Mai, his wife having killed herself years earlier. It seems she was an early casualty of a suicide virus engulfing the city. Hundreds succumb to the disease every week, and several bizarre cults have sprung up dedicating themselves to the “Death God.”

Enter Professor Aleo, a mad genius who lives in a secluded castle with his humanoid “wife” and hunch-backed assistant. Aleo was once a professor at Sadusawa’s school but was fired for his morbid experiments. He and Sadusawa need one another: Aleo may know the origin and cure of the suicide disease, which Sadusawa believes he may be suffering from. Sadusawa’s daughter Mai, meanwhile, can use her psychic powers to bring to life Aleo’s two “monsters,” stitched-up human cadavers with which, in a plot point lifted from FLESH FOR FRANKENSTEIN (1973), he plans to start an emotionless master race.

Mai fulfills her duty: the corpses are brought to shuffling life. Unfortunately for Aleo, during the creatures’ brief sojourn among the living they learn a few too many dreaded human emotions. When the time comes for them to mate and seed the new race, the critters find themselves unattracted to each other and refuse to have sex. That’s when all Hell really breaks loose…

LAST FRANKENSTEIN is almost entirely plot-driven. With such an approach certain characterizations inevitably suffer (most notably that of Sadusawa’s daughter Mai), and it takes at least two viewings to fully grasp the plot’s countless elements, but the film is always compelling. There are moments of out-and-out surrealism, gore and even some demented humor. Kawamura has created a challenging, exhilarating and disturbing work that occasionally recalls the cinema of filmmakers like David Cronenberg and Kenji (BLIND BEAST) Matsumara, but remains uniquely his own.

The camerawork tends to be mostly static, while the shots, beautifully composed though they are, tend to be often held for inordinately long periods. The tone is grim and somber from the first frame to the last (which may turn off American audiences, and is probably the prime reason it has never been distributed in the US). Although Kawamura’s helming occasionally descends into artsy self-consciousness, it’s always watchable.

This isn’t to say that THE LAST FRANKENSTEIN is slow paced; if anything it may move a shade too fast. But there’s one thing it certainly isn’t: boring.

Vital Statistics

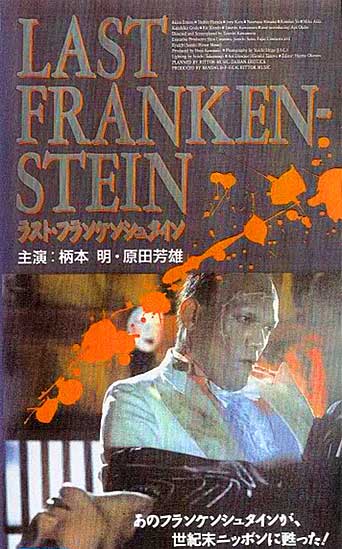

THE LAST FRANKENSTEIN (RASUTO FURANKENSHUTAIN)

Director: Takeshi Kawamura

Screenplay: Takeshi Kawamura

Cinematography: Yôichi Shiga

Editing: Hajime Okayasu

Cast: Akira Emoto, Yoshio Harada, Aya Otabe, Juro Kara, Takeshi Kawamura, Satoshi Koji, Rie Kondoh, Naomasa Musaka, Masahiko Shimada, Michiko Yamamura, Kimiko Yo