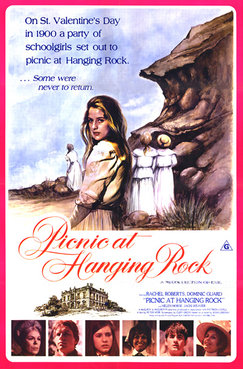

There’s never been another horror movie like this Australian masterwork—actually, it’s like no other film of any kind. The eerie story of three schoolgirls and an elderly governess who disappear during an outing at a prehistoric rock formation, Peter Weir’s PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK is a dreamy, hallucinatory mood piece that exerts a powerfully disquieting spell. A moneymaker in its day, the film, with its measured pacing and inconclusive narrative, now plays like art house fare. But as far as I’m concerned it’s required viewing for horror buffs of any stripe.

There’s never been another horror movie like this Australian masterwork—actually, it’s like no other film of any kind. The eerie story of three schoolgirls and an elderly governess who disappear during an outing at a prehistoric rock formation, Peter Weir’s PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK is a dreamy, hallucinatory mood piece that exerts a powerfully disquieting spell. A moneymaker in its day, the film, with its measured pacing and inconclusive narrative, now plays like art house fare. But as far as I’m concerned it’s required viewing for horror buffs of any stripe.

PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK was initially released, to great success, back in 1975 (although it didn’t make it to the US until several years later, after its director’s subsequent film THE LAST WAVE had already been distributed). It’s generally credited with putting Australian cinema “on the map” and jump-starting the career of its talented director Peter Weir, whose second feature it was (THE CARS THAT ATE PARIS came first, and was followed by the likes of GALLIPOLI, WITNESS, DEAD POETS SOCIETY, THE TRUMAN SHOW and MASTER AND COMMANDER).

The film was faithfully adapted from a popular 1967 novel by Joan Lindsay that may or may not have been inspired by a true story that allegedly occurred back in 1900. The book is written in unadorned documentary style and concludes with an apparently real summary of the events that claims to be “From a Melbourne newspaper, dated February 14, 1913”. Much has been about the true story aspect in the film’s publicity, but that issue was in question from the start. See Lindsay’s forward to the novel, which states, “Whether PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK is fact or fiction, my readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen hundred, and all the characters that appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important.” A follow-up book entitled THE SECRET OF HANGING ROCK, containing the book’s suppressed final chapter, did little to clarify matters.

In 1998 Peter Weir decided to create a “Director’s Cut” of PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK, and, in direct contrast to most director’s cuts, actually made the film 8-9 minutes shorter than it was initially, losing a crucial subplot in the process. This wouldn’t be nearly as annoying to me if this new cut were not the only available version…but alas, it is. Certainly the film is worth viewing in any form, but I think viewers deserve a chance to experience it in its original and (I believe) definitive version.

The story: on St. Valentine’s Day in 1900 a party of schoolgirls from the prestigious St. Appleyard College embarks on a day-long trip to Hanging Rock, a million-year-old volcanic rock formation located in the Australian outback. After an afternoon spent lounging at the base of the rock four of the girls, led by the angelic Miranda, elect to explore the formation on their own. The girls climb the rock, finding themselves overcome with a strange turpitude. After a catnap on one of Hanging Rock’s higher levels they continue the climb, but in dreamy, trancelike fashion. The dumpy Edith is the only one of the four able to resist whatever force seems to be guiding the other girls—terrified, Edith runs back down, on the way passing (she later reports) one of the governesses running up the rock in her pantaloons.

That night the expedition returns to the school without the three girls or their governess. An extensive search is instituted by the local police department, but no trace of any of the missing persons is uncovered. However, Michael, a young English gentlemen holidaying in the area who caught of glimpse of the four girls embarking on their fateful climb, undertakes his own investigation of Hanging Rock. He becomes overcome with a turpitude similar to that which infected the disappearees, but not before he discovers one of the missing girls, the feisty brunette Irma, lying unconscious in a crevice. Irma, who remembers nothing of what happened on the Rock, is immediately taken back to Appleyard College (lucky her).

The school has fallen into disarray since the disappearances: several parents have disenrolled their children and the severely repressed headmistress finds her mental state disintegrating. She cruelly takes out her frustrations on the orphaned Sara, who was in love with Miranda and now finds it difficult to cope. The repercussions of the events that occurred on St. Valentine’s Day continue to effect the lives of all involved: Irma initiates a tentative romance with her savior Michael (this entire subplot was excised in the director’s cut), the schoolgirls collectively turn on her, Sara takes her own life and the headmistress commits a most shocking and unexpected act.

The overall feel of PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK is best summed up by the Edgar Allen Poe quote intoned over the opening credits: “All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.” From the start a languid, hallucinatory atmosphere is established that’s flawlessly sustained. It’s a testament to Peter Weir’s artistry that he managed to conjure such vivid and hypnotic cinema from Joan Lindsay’s frankly dull novel—it’s responsible for the lopsided narrative that, once the picnic of the title is over and the girls have disappeared, meanders listlessly toward a perversely inconclusive non-ending. In Weir’s hands, however, none of that really matters.

The work of Weir’s collaborators is uniformly top notch, with Bruce Smeaton’s peerlessly haunting score and Russell Boyd’s evocative cinematography being particular stand-outs. Another stand-out is the Hanging Rock itself, a wondrously strange, ominous formation that ranks with the most striking movie scenery of all time.

The cast contains many sharp performers, including the British Rachel Roberts as the monstrous headmistress and the striking Helen Morse as a sympathetic French governess. But it’s the achingly beautiful eighteen-year-old Anne Lambert, as Miranda the “Botticelli Angel”, who makes the greatest impression. Lambert’s screen times amounts to very little (she being one of the disappearees), but her angelic presence suffuses the entire film. It’s no surprise that a shot of her face from an early scene has become a signature image for both the film and modern Australian cinema.

Ultimately PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK demands multiple viewings to be fully appreciated. What feels at first like a simple exercise in “macho mysticism” (to borrow a phrase from one unenthusiastic review) gradually reveals itself to be an unusually complex, multilayered piece of work with an elaborately constructed soundtrack that juxtaposes sounds of slowed-down earthquakes and airplane exhaust as part of a masterfully achieved audiovisual palette. Be advised, though, that the mystery at the film’s center is never made particularly clear, regardless of how many times one views it.

Vital Statistics

PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK

Picnic Productions Pty. Ltd.

Director: Peter Weir

Producer: Patricia Lovell

Screenplay: Cliff Green

(Based on a novel by Joan Lindsay)

Cinematography: Russell Boyd

Editing: Max Lemon

Cast: Rachel Roberts, Dominic Guard, Helen Morse, Jacki Weaver, Anne Lambert, Christine Schuler, Karen Robsen, Frank Gunnell, Jane Vallis, Kirsty Child, Vivean Gray, Margaret Nelson, Ingrid Mason, Jenny Lovell, Janet Murray, Vivienne Graves, Wyn Roberts, Kay Taylor, Garry McDonald