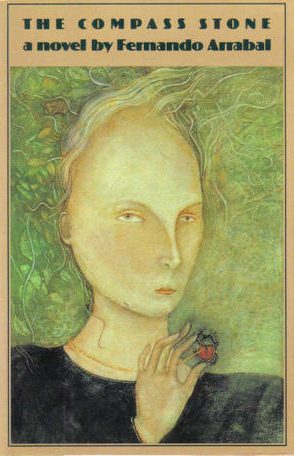

By FERNANDO ARRABAL (Grove Press; 1987)

By FERNANDO ARRABAL (Grove Press; 1987)

Is this the weirdest novel I’ve ever read? Can’t say, but I’m positive I’ll never read anything stranger.

Fernando Arrabal is Spain’s grand master of the avant-garde, a playwright, artist, filmmaker and sometime novelist. THE COMPASS STONE (LA PIERDA ILLUMINADA), translated by Andrew Hurley, is one of a handful of Arrabal novels available in English (the others are BAAL BABYLON, THE BURIAL OF THE SARDINE, THE TOWER STRUCK BY LIGHTNING and THE RED VIRGIN), and for me the standout, an astounding torrent of madness, perversion, hallucination and murder, but graced with a probing, boldly intellectual edge. It’s told from the point of view of an unnamed teenage girl living in a vast, crumbling mansion run by her father, known only as “the Maimed One”, who spends his days watching TV and decrying the decadence of modern society. “The Sisters”, two gluttonous handmaidens, are on hand to attend to his every need.

The protagonist spends her days studying insects, pondering life and its many mysteries inside The Greenhouse, the back portion of the mansion. Her nights are spent wandering the surrounding streets. There she lures four lecherous men into having sex with her and slits their throats with a straight razor at the moment of orgasm. Why? No concrete reason is ever given.

The novel can be read on one level as a parody of conventional detective fiction, with a peripheral character, a friend known only as S-, constantly speculating about the murderess’s identity, eventually conjuring a physical profile that comes remarkably close to the truth. The actual murderess has no discernible reaction to his revelations, responding as she does to everything in her life, with complete and utter passivity.

What the narrator has in place of a personality is questions—innumerable questions. Questions about the behavior of herself and her companions, about humanity, about life and the universe and everything else. Every page, you can be sure, contains questions a’plenty, with the narrator’s every observation triggering a veritable flood of unanswerable queries. About a man giving her oral sex she wonders, “What was it the stranger sought from me? Was he deep-sea diving? Was he trying to pass through fire without being burned? Did he plunge into that fetidness to tap the fountain-source of energy? Of spontaneity? Of life itself?” At another point she ponders, “Will all this be consumed one day? At the end of what term of eternity? Will all be dust one day? Hermetic particles of ash sunk into invariability? At what moment will there no longer be any distinction between the rusted shell of a steel ball bearing and the cadaver of a green caterpillar?”

Another pivotal character is K-, a sumo wrestler who longs to commit Hara-Kiri together with the protagonist (“Was for K- the essential thing to exist like the blink of an eye? And in that terribly short length of time, did he really propose to be happy?”), and D-, a wealthy nutcase who keeps a masochistic woman chained up in the basement of his castle and stages a delirious, apocalyptic orgy that memorably climaxes the book (“Moments before the party began, among the guests there started springing up a kind of collective abandon. As a consequence of sexual promiscuity? Did it incite still other abandons? To those acts most in keeping with guests’ recognition of their own personalities?”).

Arrabal was always an innovator, boldly creating his own rules, and this book, while following no known fictional dictates, has a construction as rigorous and disciplined as that of a romance potboiler. It alternates past and present, reverie and description, reality and hallucination in a manner that dimly recalls crazed classics like Iain Banks’s THE WASP FACTORY and Jose Donoso’s THE OBSCENE BIRD OF NIGHT, but is pure Arrabal through and through.

Of course, as with all truly bizarre works of literature, I can’t quite escape the niggling suspicion that THE COMPASS STONE may just be complete nonsense, a pretentious exercise in highbrow perversion. Yet, as in all of Arrabal’s fiction, there’s a real sense of intelligence and conviction. It’s by no means an easy read (although at 165 pages, it is at least a short one), but for those willing to open themselves to Arrabal’s peculiar genius I guarantee the experience will be a memorable one.