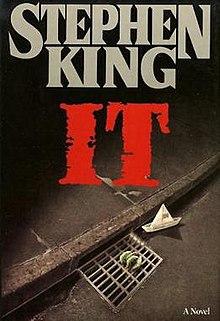

By STEPHEN KING (Viking; 1986)

By STEPHEN KING (Viking; 1986)

This is Stephen King’s opus. As the man himself has said of IT, “Everything I know is in that book.” The 1,138-page(!) IT also marked the start of the epic horror novel boom of the late eighties and nineties (when it seemed that every genre novel had to be over 500 pages). It’s an undeniably impressive achievement in many respects, as well as an extremely bloated, scattershot and misconceived work—in short, it’s pure Stephen King from start to finish.

“Everything I know is in that book.”

The three decade-spanning narrative is one of King’s stronger and more original works. It posits that back in 1958, in the small Maine town of Derry, a group of outcast youngsters form a self-monikered “losers club” to (among other things) fight a shape-shifting monster who’s been killing their friends and relatives. The kids complete the job, or seem to, but 28 years later the “It” returns, prompting the now-adult protagonists, who’ve forgotten much of what occurred all those years ago, to head back to Derry and take on the It a second time. In this way King spins a fitfully epic account with a potent metaphor about the necessity of facing up to childhood anxieties.

IT’S sprawling canvas leaves ample room for the type of excessiveness in which King, Mr. Diarrhea-of-the-Word-Processor himself, specializes. There are lengthy asides detailing the sordid history of Derry and the It residing therein (which, we learn, came from outer space in prehistoric times), much miscellaneous banter among the protagonists during their childhood and adult years, and several intense encounters with neighborhood bullies (including an aptly named “Apocalyptic” rock fight) that read like the climax of a RAMBO movie.

In the same vein are the countless freak-out sequences in which It accosts the protagonists in various guises: a werewolf, giant bird, flying leech and, most prominently, a scary clown named Pennywise (King was planning on abandoning the genre at the time, and so had the idea of trotting out all the monsters he could think of in a sort of last hurrah). The sequences are all related in a raised voice, and grow tiresome after awhile, showcasing some definite conceptual flaws (wouldn’t it be smarter on the part of It to lure kids into its clutches with pleasing and seductive guises rather than scary ones?), as well as the shortcomings of the horror novel as a whole: it’s been argued that the genre works best in short story format, and IT offers ample proof of that statement.

Of course, there’s plenty of authentically good stuff herein. The characterizations are uniformly strong, with the child protagonists—Bill the stutterer, Ben the fatso, Beverly the put-upon tomboy, Mike the token black kid, Stan the neat freak, Richie the incurable wise-ass and the sickly Eddie—all registering as individuals whose complexities stretch far beyond their various afflictions (a good thing, because otherwise the 1958 portions of this book would probably read like THE GOONIES). The adult protagonists are also extremely well drawn, but King’s brilliance is in his spot-on evocation of the world of childhood.

The novel also contains perhaps the most outrageous sequence Stephen King has ever written. I refer to the climax, in which the Losers Club descends into the sewers to vanquish It for the first time, an act the 11-year-old Beverly tops off by having sex with her six companions. Her rationale, that taking the boys’ virginity will somehow strengthen their group bond, is a weak one (the adult Beverly is understandably dumbfounded upon recalling the event), while the author’s reasoning can only be guessed at. I will say this for the sequence: it provides a concluding jolt that the rather limp final confrontation doesn’t.

Regarding that final confrontation, it intercuts the exploits of the Loser’s Club with those of their adult selves, both facing down Its final and apparently most representative form: a big spider. The problem is that after all that’s come before this dual showdown feels a tad mundane (considering all the amazing guises Its assumes, a spider doesn’t seem like such a big deal) and fails to provide the type of mind-blowing summation King was evidently trying for.

Yet I do recommend IT as the first and last step in all things Stephen King. The novel neatly encapsulates his strengths as a novelist, as well as quite a few of his weaknesses.