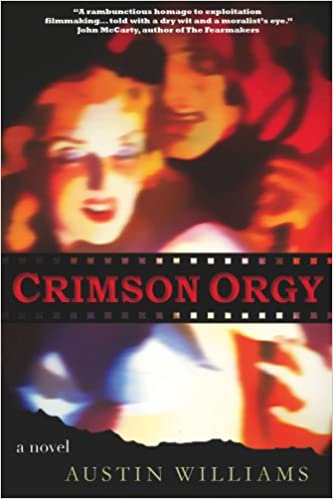

By AUSTIN WILLIAMS (Borderlands Press; 2008)

By AUSTIN WILLIAMS (Borderlands Press; 2008)

As far as I know this is the only horror novel to be set in the world of 1960s-era exploitation moviemaking. As you film buffs well know, that was the time and milieu of H.G. Lewis’ fabled proto-splatter classic BLOOD FEAST (1963), and proves to be such fertile ground for a fictional horror story I wonder why more writers haven’t mined it.

The first novel by Austin Williams, CRIMSON ORGY has a suitably nerdy framework: it opens and closes with articles about an obscure sixties era splatter epic called CRIMSON ORGY, which gained notoriety due to rumors that it contained footage of an actual killing. We learn what actually occurred during the making of CRIMSON ORGY in the bulk of the novel, and the production turns out to be every bit as sordid as it’s been cracked up to be.

The filming takes place a couple years after BLOOD FEAST, and in the same South Florida locale. Filmmaker Sheldon Meyer and producer Gene Hoffman, who like Lewis (and his producing partner David F. Friedman) have found minor success on the nudie film circuit, are looking to outdo the excesses of BLOOD FEAST in CRIMSON ORGY (admittedly an extremely highbrow title for a Southern-made exploitation film, but that fact is at least addressed by the characters). The alluring but inexperienced Barbara Cheston is cast in the lead role, with the more seasoned pretty boy Vance Cogburn essaying her male counterpart and Jerry Cooke, a creepy dude who takes the concept of method acting a bit too seriously, as the villain.

The one-week shoot, filmed on location in the town of Hillsborough Beach, runs into trouble almost immediately when a local deputy forces Meyer to give him a speaking part in the movie—and turns in a performance that’s beyond wooden. More problems arrive in the form of a hurricane, a stolen film reel, the off-set demise of a supporting player, a none-too-discreet affair between the leading actors, a mentally unstable crewmember and some Hillsborough Beach locals unaware that a movie is being filmed in their midst. The true natures of the film’s makers are another pressing concern, especially after Vance finds a severed arm among Hoffman’s personal things that looks a bit too realistic for comfort.

Austin Williams relates this twisted account with a great deal of slow-building suspense and convincing detail, and layers in discussions of many pressing real-life issues brought up by splatter films like the one. In this way Williams provides a heartfelt tribute to exploitation movies of yore while simultaneously critiquing their anything-for-a-kick sensationalism. Only the dialogue detracts from the overall experience, being far too modern in its idiom and liberal use of profanity to be convincing as the verbiage of 1960s-era Southerners.

Some of the happenings, particularly those of the final pages, are horrifically gory, yet none of it ever seems the slightest bit implausible, which is the book’s most impressive feat. Anyone who’s ever worked on a low budget film shoot will recognize the pratfalls faced by these characters, and also the potential for especially nasty accidents like the one that climaxes this novel.