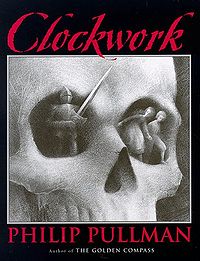

By PHILIP PULLMAN (Scholastic; 1998)

By PHILIP PULLMAN (Scholastic; 1998)

Children’s fiction can be insufferable, burdened as it often is with weak imagination and plain bad writing that would never pass muster in a grown-up publication. But on occasion kid lit has virtues other types of fiction don’t. This is the case with the YA novella CLOCKWORK, which appeals mostly because of its ingeniously constructed multi-pronged narrative that flows like—yes—clockwork. It has at least one big mark against it (I’ll be getting to that), but for the most part it’s a neat little book that will likely be appreciated more by sophisticated adults than its intended audience.

The writer was Philip Pullman, who knocked out this tale in between the second and third volumes of his famed HIS DARK MATERIALS trilogy. Pullman, as he’s proven in the HDM books, knows how to craft sinuous prose and tell a gripping story. In CLOCKWORK, set in a German village during “the old days,” he’s come up with an immensely clever bit of dark imagination containing all the wit and the moral fervor of the classic fairy tales.

Among the disparate characters Pullman weaves into this tapestry—actually, as the opening page states, it’s “a series of events, all fitting together like the parts of a clock, and although each person saw a different part, no one saw the whole of it”—are Karl, an apprentice clockmaker who’s missed his deadline for creating a mechanized figure for the giant town clock; Prince Florian, a clockwork boy whose cogs are in danger of winding down; Fritz, a writer who has come up with a macabre tale without an ending; Gretl, a young woman who enters the fray after being attacked by a mechanical knight; and Dr. Kalmenius, a demonic mechanist who may be the Devil himself.

Quite a few elements from classic tales—PINOCCHIO, THE WIZARD OF OZ, E.T.A. Hoffman’s THE SANDMAN—are woven into CLOCKWORK, which frankly isn’t up to their high standards. Pullman’s primary failing? An overly abrupt and perfunctory happy ending. Although the proceedings are often far scarier and more intense than you’d expect from a kid book, the final page is very much in keeping with such fiction, even going so far as to employ that most hackneyed of terms, “Happily Ever After.” Pfooey!!