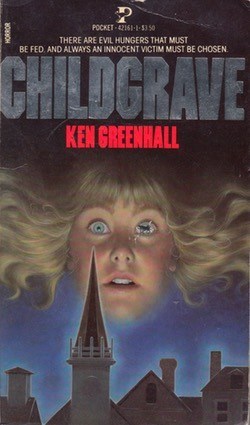

By KEN GREENHALL (Pocket; 1982)

By KEN GREENHALL (Pocket; 1982)

The third novel by the woefully underrated Ken Greenhall, who as usual delivered a strikingly unique and intelligent tale. The overriding subject is one that preoccupied Greenhall’s fiction: love, which is viewed not as a pleasant diversion nor an all-conquering panacea, but as a complex and oft-destructive entity whose effects are far-reaching. As CHILDGRAVE’S narrator admits early on, “I’ve been in love twice, and regardless of what you’ve heard elsewhere about the experience, I’m not sure I recommend it.”

That narrator is Jonathan Brewster, a widowed NYC photographer raising a five-year-old daughter. Jonathan meets the eccentric harpist Sara Coleridge at a concert and is immediately smitten. It’s Jonathan’s daughter Joanne who makes the initial introduction, which given what ultimately occurs seems quite fitting. Sara entreats Jonathan not to involve himself with her but he can’t help himself, and neither can she. They’re in love, after all, which here becomes the source of all the unpleasantness to come, and the primary reason this book is categorized as horror.

As this wholly eccentric love affair commences, Jonathan notices a most inexplicable oddity in his photographs: long-dead people start turning up alongside the still-living subjects. This naturally attracts a lot of attention, and even a degree of fame. It’s that attention that drives Sara away around the halfway point, leading an increasingly desperate Jonathan to track her to the small New York town where she grew up: a place called Childgrave.

As described here, Childgrave serves essentially the same purpose as the imaginary kingdom of El Rey did in the final chapter of Jim Thompson’s THE GETAWAY: a surreal purgatory where the amoral lovers at the novel’s center are forced to account for the recklessness of their actions. Jonathan is drawn to live in Childgrave due to his love for Sara, but the focus is on Jonathan’s young daughter Joanne (who admittedly came in second in his affections once Sara entered the picture). Childgrave, you see, is named after a young girl murdered in the area three hundred years earlier, which has given rise to a tradition in which a girl aged 1-5 is sacrificed on Christmas Eve. The victims are chosen by lottery, and Joanne, not yet having reached her sixth birthday, is among the candidates.

There’s a touch of the late Robert Aickman in the novel’s frank acceptance of supernatural phenomena, and also its psychologically-based narrative. The phenomena of dead folk appearing in Jonathan’s photographs is never explained, which combined with the gambit of waiting until past the halfway point to introduce Childgrave violates any number of fictional precepts. Yet Greenhall’s freeform construction, like Aickman’s, is accepting of such eccentricity, not least because the narrator, as is intimated on numerous occasions, isn’t entirely reliable.

Greenhall, as was his custom, provides a great deal of thoughtful discourse on subjects ranging from the bonds of community to the effects of religion, which are nearly as destructive as the love affair that powers the novel. Another Greenhall custom is the unsettled ending, a resolution that seems entirely appropriate given the thoughtful and unsparing bent of CHILDGRAVE, which despite its surreal air is ultimately quite redolent of the conundrums and complexities of real life.