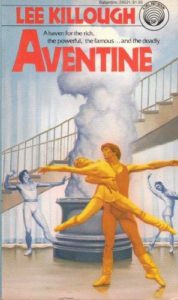

By LEE KILLOUGH (Del Rey; 1981)

By LEE KILLOUGH (Del Rey; 1981)

A most interesting science fiction pastiche, consisting of seven stories set in and around an interplanetary resort called Aventine. Located on a distant planet, Aventine is a former artists’ colony that has been transformed into a kaleidoscopic playground for the rich and famous. This place, admittedly inspired by J.G. Ballard’s VERMILLION SANDS, is marked by “cosmetisculpture” surgeons who guarantee lifelong beauty for their patients, furniture whose shapes match peoples’ moods and ever-present holograms. Of course, in true J.G. Ballardian fashion, Aventine’s carefree aura only serves to inflame the dark instincts of its residents, with meticulously planned murders being a disturbing constant.

The first of AVENTINE’S stories, “The Siren Garden,” was initially published back in 1974. It’s the most conventional, and so least interesting, of the book’s contents, being about singing crystals whose properties are potentially deadly to humans. It’s followed by “Tropic of Eden,” a Philip K. Dickian depiction of a creator of moving sculptures and two strange women whose true connection is more intimate than it initially seems. “Tropic of Eden” effectively sets the tenor for the remaining stories, most of which are told from the point of view of inquisitive men attempting to connect with strange women in Aventine.

The most interesting of the book’s tales is “A House Divided,” about a man’s relationship with a schizophrenic woman harboring two very distinct personalities—a condition that doesn’t seem terribly out of place in Aventine. I also enjoyed “Ménage Outré,” about a seductive plastic surgeon who delights in turning people into freaks, with her latest subject being the sister of the story’s haughty narrator.

Rounding out the book are “Broken Stairways, Walls of Time,” another Phil Dickian exploration of appearance vs. reality, presented in the form of a woman who utilizes extensive holographic images of herself; “Shadow Dance,” involving a choreographer looking to create an infrared dance show for a mysterious woman; and “Bête et Noir,” about a type of method acting that involves literally transforming into another character, to the point that the actor’s true identity is totally subsumed. It all adds up to a strong and readable piece of thoughtful science fiction with an excellent sense of place. My only real problem with these tales is that several of them, “A House Divided” and “Ménage Outré” in particular, could have stood to be much longer.