By D.P. WATT (Eibonvale; 2010/13)

By D.P. WATT (Eibonvale; 2010/13)

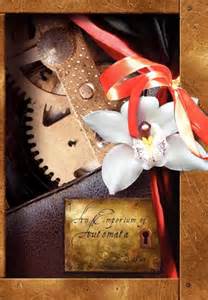

A most welcome reprinting of a collection originally published in 2010 by Ex Occidente Press, who specialize in extremely expensive limited editions. For this trade paperback version Eibonvale Press provided a gorgeous cover design, but of course it’s the content that really makes this book one of Eibonvale’s finest publications to date (let’s hope Eibonvale, or somebody, gets around to reprinting the same author’s other Ex Occidente publications).

D.P. Watt has a decidedly unique imagination and a love of esoteric wordplay (sample sentence: “I had not taken you for one who skulks behind the scenes to see God’s entrance debased to pure mechanism”). His writing is reminiscent of horrormeisters like Thomas Ligotti and Robert Aickman, yet it displays the verve, literary mastery and idiosyncratic worldview that denote a standalone master of the form.

The book is divided into three sections, starting with “Phantasmagorical Instruments.” This section includes “Erbach’s Emporium of Automata,” featuring fabulous automatons and an aura of archaic quasi-decadence that permeates the remainder of the contents of “Phantasmagorical Instruments,” and also the book as a whole. “They Dwell in Ystumtuen” concerns a woman who murders her infants in the 19th Century, an act whose reverberations stretch well into the present. There’s also “The Butcher’s Daughter,” a photo-illustrated account of the discovery of old postcards and diaries that shine a new light on an old murder case, the Aickmanesque “Room 89,” an altogether unexpected take on some hoary haunted house tropes, and “All his Worldly Goods,” a most audacious portrayal of a man haunted by (among other things) an actual horror story: “When I was Dead” by Vincent O’Sullivan.

The second and shortest section, “Geneological Devices,” features the highly eccentric “Telling Tales,” told from the point of view of a ghost that manifests itself as a crackle on a telephone line. “Zarathustra’s Drive-Inn” is ever odder, involving an avant-garde eatery and a most peculiar dream.

The book’s final portion is “Ex Nihilo.” It features “Pulvis Lunaris, or the Coagulation of Wood,” about a meeting in Prague interrupted by a bizarre puppet show. In “The Subjugation of Eros” the markings on a school desk draw a naïve boy into a dark and obsessive universe, while in “I < O” a man slowly disappears, conveyed by words that actually “vanish” (through dim or nonexistent printing) off the page. “Memento Mori” depicts a thief’s ensnarement by a shadowy antique dealer, and by extension the self-defeating impulses infecting all collectors. Finally there’s “The Tyrant,” a disturbing evocation of world-shaking tyranny that, tellingly, is related in the second person—a device that proves ideal in revealing the identity of the tyrant: “You. Unbounded, endless you.”