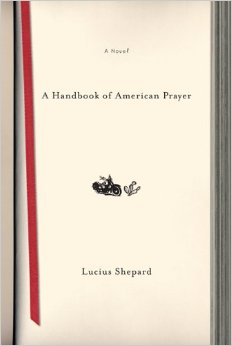

By LUCIUS SHEPARD (Thunder’s Mouth Press; 2006)

By LUCIUS SHEPARD (Thunder’s Mouth Press; 2006)

An extremely literate and well written novel that must nonetheless be classified as a disappointment. It’s a quirky take on faith and devotion in early 21st Century America by an author, the late Lucius Shepard, who I’d expect would have an especially unique and profound take on the subject—yet this novel’s insights are far from profound, and its narrative shockingly pedestrian. It’s readable, certainly (I have yet to come across a Shepard novel that isn’t), but should have been far more than it is.

It’s about Wardlin Stuart, a bartender who kills a man in a scuffle. Wardlin is sent to prison for the crime, and while incarcerated writes a series of prayers that take the form of eccentric poetry he terms “prayerstyle.” Before long he’s crafting prayers for his fellow inmates and strangers—prayers that always seem to come true.

Wardlin continues writing prayers for himself and others after he’s released. He settles down in Arizona with a comely woman he met in prison, and invents a deity he dubs the God of Loneliness. Wardlin also publishes a prayerstyle compilation called A HANDBOOK OF AMERICAN PRAYER that becomes a bestseller, and makes him a bonafide media star (thus allowing Shepard to take some potshots at real-life media stars, Roger Ebert in particular). The book attracts the attention of a TV preacher who becomes obsessed with taking Wardlin down, especially after he publicly shames said preacher.

Another intrusive personage in Wardlin’s life is Darren, a freaky individual who knows a lot about Wardlin and his enemies, and may in fact be the God of Loneliness personified. As described here Darren isn’t a particularly interesting character, and neither, for that matter, is Wardlin himself.

Previous Lucius Shepard novels like KALIMANTAN, LIFE DURING WARTIME and THE GOLDEN had a visionary grandeur that A HANDBOOK OF AMERICAN PRAYER appears to building toward but never attains. The novel doesn’t work as noir, satire or magic realism, although it partakes of all those formats, and fizzles out in a climax that’s distinctly anticlimactic. The message? That self-deification is a bad idea, something I think we can all figure out on our own.