Here we’re going to discuss titles: movie and book titles, to be exact. Titles are undervalued by many, but their importance cannot be overestimated. It’s not uncommon in the movie world for a title to be selected before a script is written, or, in some cases, a concept is selected (which is how we got FRIDAY THE 13th). On the subject of title selection opinion generally falls into one of two camps: those who believe a title functions primarily as a come-on to lure potential viewers/readers, and those who feel that anything goes so long as the title accurately reflects a book/movie’s contents.

Here we’re going to discuss titles: movie and book titles, to be exact. Titles are undervalued by many, but their importance cannot be overestimated. It’s not uncommon in the movie world for a title to be selected before a script is written, or, in some cases, a concept is selected (which is how we got FRIDAY THE 13th). On the subject of title selection opinion generally falls into one of two camps: those who believe a title functions primarily as a come-on to lure potential viewers/readers, and those who feel that anything goes so long as the title accurately reflects a book/movie’s contents.

Nonsense Titles

Myself, I tend to side with the former camp. Certainly I don’t disagree that descriptive titles are a good idea, but the fact remains that quite a few of the best titles are essentially meaningless.

I admittedly have a personal take on this issue that stretches back to the fifth grade. It was then that a teacher flunked a book report I’d written on Judy Blume’s SUPERFUDGE because I couldn’t explain the title, which was, in fact, unexplainable (the best I could come up with was that the book featured a kid nicknamed Fudge who at one point is taken to see SUPERMAN).

In retrospect I’m just glad I didn’t try and explain FROTH ON THE DAYDREAM, STRAW DOGS, BURNT WATER or RESERVOIR DOGS, all of which I consider to be great titles even though all are unexplainable. That’s especially true of the latter title, a nonsensical phrase (allegedly inspired by a mispronunciation of the French film AU REVOIR LES ENFANTS) that nonetheless remains one of the most memorable monikers I know. Ditto BLADE RUNNER, a movie title that outside of being the name of its hero’s profession has no evident meaning; it was apparently chosen simply because it sounded cool.

Misleading Titles

It’s important, I believe, not to mislead audiences with a title. That was the case with the 1977 film SORCERER, certainly one of the most misleading monikers of all time (the film, for those who don’t know, does not involve a sorcerer). Further examples abound in the world of literature, including THE SYSTEM OF DANTE’S HELL, SATAN’S SISTERS and HOW OLD WAS LOLITA?, titles that are all quite specific about subjects that don’t actually turn up in the novels they adorn.

Really Good Titles

Ideally, a title should function as both a lure to potential readers/viewers and also an adroit summation of a book or movie. In this best-of-both-worlds category are JAWS, certainly one of the most perfectly chosen single word titles ever; TAXI DRIVER, which reflects the movie’s content in its rather harsh bluntness (were it titled THE TAXI DRIVER the effect would be quite different); THEY THIRST, arguably the ideal title for a vampire story; NEKROMANTIK, a made-up term perfect for a film about necrophiles; and the ever-popular CRASH, a highly in-demand title that has adorned no less than four movies, a TV series and over a dozen books, but in my view was best utilized in the J.G. Ballard novel of that name and the David Cronenberg movie adaptation, for which CRASH nicely sums up both the contents and their overall impact.

Of course, in discussing the evolution of modern titles positive and otherwise one profound influence looms above most every other…

Hollywood

Hollywood has much to answer for culturally, including single-sentence plot summaries and recycled concepts, both of which have spread throughout the world like some kind of virus. Another area in which Hollywood’s influence is evident is in titles, with marquee-friendly two and three word monikers prevailing in the movie world.

Take the case of David Lynch. Mr. Lynch is a painter and songwriter as well as one of the world’s most idiosyncratic filmmakers, but, puzzlingly enough, in naming his movies he tends toward short and non-descriptive monikers such as BLUE VELVET, THE STRAIGHT STORY, MULHOLLAND DRIVE and INLAND EMPIRE. Yet his painting and song titles are somewhat more evocative: “Oww God, Mom, the Dog He Bited Me,” “Billy Was Halfway Between His House and the Sickening Garden of Letters,” “The Night Bell With Lightning,” “The Line it Curves,” etc. No one, it seems, is immune from the Hollywood malaise, even someone as uncompromising as David Lynch.

Tinseltown apologists will no doubt argue that its simplistic titles are selected via complex tracking and testing methodology, and so are only reflecting the likes of paying audiences. Maybe, but it was that very testing process that gave us snooze-worthy movie titles like THE PROPHECY (which replaced the more evocative GOD’S ARMY), BOUND BY HONOR (the theatrical moniker slapped on the urban drama BLOOD IN, BLOOD OUT) and POINT OF NO RETURN (which adorned the American remake of the French LA FEMME NIKITA).

That latter title, a choice so lame the movie’s star Bridget Fonda allegedly refused to say it, offers an example of an especially annoying Hollywood convention. I’m referring here to clichéd phrases in place of proper titles, which since the advent of the 1990s have proliferated: WHERE THE HEART IS, WHATEVER IT TAKES, IN TOO DEEP, STRAIGHT FROM THE HEART, THE NEXT BEST THING, THE WHOLE NINE YARDS, etc, etc, etc. The rationale, I’m guessing, is that familiarity with those phrases, generic though they are, will make moviegoers more likely to open their wallets. Familiarity is one of modern-day Hollywood’s most cherished tactics when it comes to titles, be it through clichés like those above or carefully chosen words (look at all the recent women-skewering movies featuring “Wedding” in their titles), or, in some cases, letters (note how the 1992 thriller FINAL ANALYSIS shares the same two first letters as the ultra-successful FATAL ATTRACTION, which FINAL ANALYSIS’ initial director John Boorman has suggested was not accidental).

While on the subject of obnoxious Hollywood trends, here’s another: the “ing” titles so popular in the nineties. An “ing” added onto a title can work wonders, as Stephen King proved by grafting just such a suffix onto what he initially called THE SHINE (it’s not King’s fault the practice was copied in so many subsequent horror novels), but most “ing” titles are considerably less edifying: LIVING OUT LOUD, WAITING FOR GUFFMAN, BRINGING OUT THE DEAD, TEACHING MRS. TINGLE, PUSHING TIN, GIVING IT UP, DECONSTRUCTING HARRY, TELLING LIES IN AMERICA, etc.

Aside from being grammatically incorrect more often than not–-you either save Private Ryan or you don’t, there’s no SAVING PRIVATE RYAN, while you can’t invent or uninvent the Abbots, and there’s certainly no INVENTING THE ABBOTS-–these annoying suffixes give otherwise frank and declarative titles a noncommittal, neither-here-nor-there quality. I’d love to say the “ing” craze went out with the nineties, but such titles continue to proliferate in the more current likes of SAVING MR. BANKS, BREAKING DAWN, CATCHING FIRE, CHASING MAVERICKS and KILLING KENNEDY. I guess we should be happy we didn’t wind up with KILLING BILL or GETTING HIM TO THE GREEK, although I can’t help but believe that if certain old movies were released today they’d have titles like SINKING THE BISMARK or RAISING THE TITANIC.

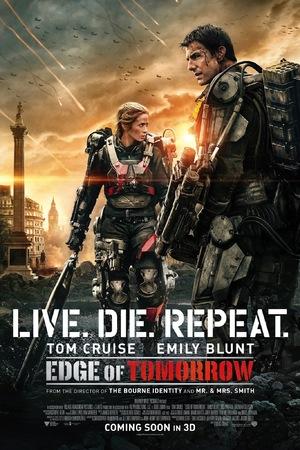

Before leaving the subject of Hollywood I’ll have to mention one Hollywood-vetted title I don’t get at all: EDGE OF TOMORROW, an eminently forgettable, utterly meaningless phrase chosen to replace ALL YOU NEED IS KILL. Granted, that latter name is quite problematic in its own right (it was taken from a novel that originally appeared in Japanese, and is probably a mistranslation), but it’s better than EDGE OF TOMORROW, which was doubtless partially responsible for that well-liked 2014 movie’s disappointing performance at the box office. The movie, incidentally, is currently listed on iTunes as LIVE DIE REPEAT: EDGE OF TOMORROW, so clearly I’m not the only one who hates that title.

Before leaving the subject of Hollywood I’ll have to mention one Hollywood-vetted title I don’t get at all: EDGE OF TOMORROW, an eminently forgettable, utterly meaningless phrase chosen to replace ALL YOU NEED IS KILL. Granted, that latter name is quite problematic in its own right (it was taken from a novel that originally appeared in Japanese, and is probably a mistranslation), but it’s better than EDGE OF TOMORROW, which was doubtless partially responsible for that well-liked 2014 movie’s disappointing performance at the box office. The movie, incidentally, is currently listed on iTunes as LIVE DIE REPEAT: EDGE OF TOMORROW, so clearly I’m not the only one who hates that title.

LIVE DIE REPEAT? Imperfect, but still superior to EDGE OF TOMORROW!

Creative Titles and their Shortcomings

It is possible, of course, to go too far with “creative” titles. The late Philip K. Dick was known for outrageously loopy monikers, and turned out some unforgettable titles like DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP? and NOW WAIT FOR LAST YEAR, but also some crummy ones like GALACTIC POT-HEALER and FLOW MY TEARS, THE POLICEMAN SAID. Dick’s contemporary Harlan Ellison also provided some great titles—I HAVE NO MOUTH AND I MUST SCREAM, LOVE AIN’T NOTHING BUT SEX MISSPELLED—but just as many clunkers; I’ve no idea what Ellison was trying to convey with short story monikers like “The Wine Has Been Left Open too Long and the Memory has Gone Flat” and “Adrift Just Off the Islets of Landerhans: Latitude 38 54’ N, Longitude 77 00’13” W,” but it doesn’t appear to have worked.

In the same category are exotic or foreign sounding titles, which certainly have their place; I truly believe the world would be poorer without titles like FASTYNGANGE, MALPERTUIS or CODEX SERAPHINIANUS. But this practice, like any other, can backfire.

The late French filmmaker Claude Chabrol had the misfortune of having most of his films released in the English-speaking world under their original French titles—such as LE BOUCHER, QUE LA BETE MEURE and L’ENFER—thus confining them largely to the highbrow art-house crowd. The problem is that those films are accessible to audiences far lower down on the social scale, as is clear from the English translations of those titles: THE BUTCHER, THE BEAST DIES and HELL, titles that, conversely, would likely turn off the latte-and-cappuccino crowd.

Literary Horror Titles: The Good, Bad and Indifferent

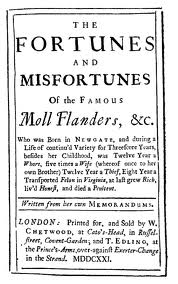

I often wonder if things were better in the olden days, when book titles frequently incorporated plot summaries (the novel we now know as MOLL  FLANDERS was initially titled THE FORTUNES AND MISFORTUNES OF THE FAMOUS MOLL FLANDERS, WHO WAS BORN IN NEWGATE, AND DURING A LIFE OF CONTINU’D VARIETY FOR THREESCORE YEARS, BESIDES HER CHILDHOOD, WAS TWELVE YEAR A WHORE…) or descriptive taglines (such as MEDUSA: A STORY OF MYSTERY AND ECSTASY AND STRANGE HORROR). This isn’t to say, however, that there aren’t great titles to be found in today’s literary marketplace.

FLANDERS was initially titled THE FORTUNES AND MISFORTUNES OF THE FAMOUS MOLL FLANDERS, WHO WAS BORN IN NEWGATE, AND DURING A LIFE OF CONTINU’D VARIETY FOR THREESCORE YEARS, BESIDES HER CHILDHOOD, WAS TWELVE YEAR A WHORE…) or descriptive taglines (such as MEDUSA: A STORY OF MYSTERY AND ECSTASY AND STRANGE HORROR). This isn’t to say, however, that there aren’t great titles to be found in today’s literary marketplace.

The acclaimed horror scribe Ramsey Campbell has a definite gift for titles. Standout examples include DEMONS BY DAYLIGHT, THE DOLL WHO ATE HIS MOTHER, THE FACE THAT MUST DIE and THE HUNGRY MOON, evocative, attention-grabbing monikers all (although that gift occasionally deserts Campbell, as in THE HEIGHT OF THE SCREAM, an altogether inappropriate choice, and OBSESSION, which errs on the side of blandness).

At the other end of the spectrum we have the titles of Jack Ketchum. Ketchum was and is one of the greatest writers on the horror scene, yet he endured over a decade of neglect. The reasons for that are myriad, but I’d argue that among them were the titles of his books, which too often were comprised of clichéd phrases like OFF SEASON, HIDE AND SEEK, THE GIRL NEXT DOOR and LADIES NIGHT. Those phrases are in all cases used ironically (i.e. OFF SEASON refers to the hunting of humans), but one has to actually read the books to understand that. A person spotting a book titled LADIES NIGHT on a bookshelf will likely think of something entirely different from what the novel provides.

Further examples of ironically used cliché monikers include MOON DANCE by S.P. Somtow, a bloody werewolf novel that, contrary to what the title infers, doesn’t contain much dancing. BLOOD SPORT by Robert F. Jones is a violent and surreal odyssey whose title misrepresents it in every respect. DANCING IN THE DARK by Joan Barfoot is an evocative account of a housewife’s descent into psychosis stuck with an altogether lame title (enough with the dancing metaphors!). OFF THE WALL by Charles Willeford is a Son of Sam bio-novel, and a title that refers specifically to the scribblings on the apartment wall of its psychotic protagonist, as well as the book’s offbeat tone…and so actually works fairly well.

As for practice of a name as the title, I’m opposed unless that name is especially unique or interesting, as in DRACULA, DAGON and GRIMSCRIBE. Obviously that’s not the case with CARRIE, DAMON, ELIZABETH, NATHANIEL, LORI or JESSICA, which I’d place in the same category as number titles, represented by the extremely catchy likes of 491, 334, 13 and 419. Yes, those are actual book titles.

I tend to cringe whenever I see the word DARK in a horror novel title, which has become obnoxiously overused in lazy two word monikers like DARK PLACES, DARK BLOOD, DARK MATTER, DARK SACRIFICE, DARK INHERITANCE, DARK HARVEST, DARK RESURRECTION, DARK DESIRES, DARK AURA, DARK DESTINY, DARK EDEN, DARK HOLLOWS, DARK CORNERS…and that’s not even taking into account the many horror novels called THE DARK or IN THE DARK. Enough already!

Yet having said that, I’ll  have to admit that in the horror world it’s often the simplest monikers that work the best. I’m referring here to two word titles starting with “The.” The late Thomas M. Disch was known for creative monikers like ECHO ROUND HIS BONES and ON WINGS OF SONG, but in his later years he opted for more straightforward choices: THE BUSINESSMAN, THE M.D., THE PRIEST and THE SUB. Achingly simple those titles may be, but they do the job.

have to admit that in the horror world it’s often the simplest monikers that work the best. I’m referring here to two word titles starting with “The.” The late Thomas M. Disch was known for creative monikers like ECHO ROUND HIS BONES and ON WINGS OF SONG, but in his later years he opted for more straightforward choices: THE BUSINESSMAN, THE M.D., THE PRIEST and THE SUB. Achingly simple those titles may be, but they do the job.

So do THE EXORCIST, THE OTHER, THE RATS, THE FOG, THE DEMON, THE TENANT and THE CEREMONIES. Sure, ECHO ROUND HIS BONES is a laudable choice, as are RESERVOIR DOGS and I HAVE NO MOUTH AND I MUST SCREAM, but my preference on titles is ultimately the same as that of most everything else: I’m for whatever works.