Hell has always played well on screen. We’ve seen the inferno depicted in countless films over the years, from 1911’s Dante inspired L’INFERNO to quite a few similarly conceived follow-ups, such as 1924’s DANTE’S INFERNO and the 1989 British television production A TV DANTE: THE INFERNO. Those, however, are all Western made depictions of the inferno. Quite a few Eastern crafted Hell movies exist that contain some of the screen’s most powerful and affecting infernos. Examples include the Hong Kong production HEAVEN AND HELL (1980), the John Woo directed TO HELL WITH THE DEVIL (1982) and the Nobuo Nakagawa helmed Japanese masterwork that overshadows every other Hell movie, Asian or otherwise: JIGOKU (INFERNO), which appeared in 1960.

Hell has always played well on screen. We’ve seen the inferno depicted in countless films over the years, from 1911’s Dante inspired L’INFERNO to quite a few similarly conceived follow-ups, such as 1924’s DANTE’S INFERNO and the 1989 British television production A TV DANTE: THE INFERNO. Those, however, are all Western made depictions of the inferno. Quite a few Eastern crafted Hell movies exist that contain some of the screen’s most powerful and affecting infernos. Examples include the Hong Kong production HEAVEN AND HELL (1980), the John Woo directed TO HELL WITH THE DEVIL (1982) and the Nobuo Nakagawa helmed Japanese masterwork that overshadows every other Hell movie, Asian or otherwise: JIGOKU (INFERNO), which appeared in 1960.

Nakagawa’s film, with its painterly widescreen visuals and unflinching depiction of the nastier reaches of the inferno (in which category it preceded groundbreaking splat fests like BLOOD FEAST and THE FLESH EATERS), remains a stunner. It’s also proven quite influential, having been remade in 1979 and ‘99, and inspired three early 1980s knock-offs: TEN COURTS OF HADES, THE HELL and RESCUE FROM HADES.

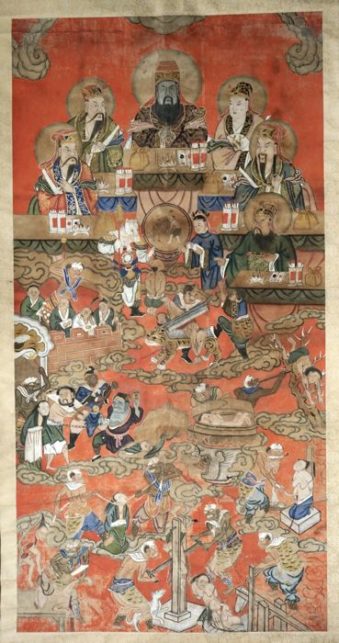

The latter films were all made in Taiwan, and partake of a distinctly Chinese interpretation of the inferno—or Diyu—that diverges mightily from the Japanese Jigoku. As outlined in the THE JADE GUIDEBOOK, originating from 19th Century China, and the 1978 Taiwanese novel JOURNEYS TO THE UNDERWORLD/VOYAGES TO HELL by Yang Zanru (both of which purport to be first-person explorations of the underworld, or East Asian versions of Dante’s INFERNO), Diyu is said to have either ten “courts” or eighteen levels, ruled over by the monstrous King Yan and his subordinate Yama Kings; peoples’ souls are exiled to these courts and/or levels in order to work off particularly grievous karmic debts, after which they’re reincarnated. TEN COURTS OF HADES, THE HELL and RESCUE FROM HADES were clearly patterned after Yang Zanru’s text, yet the influence of JIGOKU is just as evident.

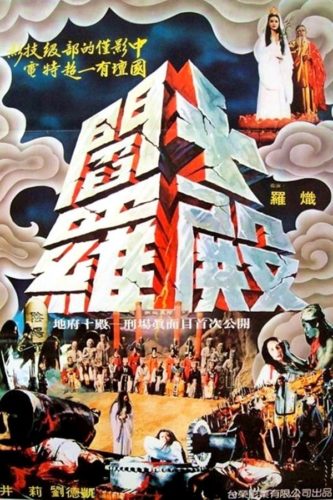

TEN COURTS OF HADES (IN HELL/SHI DIAN YAN LUO) appeared in 1981. Its helmer was the prolific Chinese director/actor Chi Lo, who here fleshed out the “ten courts” conception of Diyu. The JIGOKU influence can be seen in the overall structure, which as in Nakagawa’s film pivots on a lengthy prologue set on the mortal plane, with the entirety of the second half taking place in the underworld.

That prologue, set in feudal Taiwan, is hellaciously convoluted. It involves a dying family patriarch and a long-dead woman relative of said patriarch who enters the living world through a magic mirror. She ends up braving the darker reaches of the inferno in an effort at finding and saving the souls of her deceased family members.

The Diyu depicted in this movie is much like those elaborately adorned temples in which so many Chinese action movies take place, being an enclosed structure run by a contingent of stern men—the aforementioned Yama Kings—who oversee a plethora of horrific tortures. We see, in a succession of lingering close-ups, people being crushed, sawed in half, disemboweled, having their eyeballs plucked out of their heads and being sent down chutes from which they emerge as their new incarnation—i.e. transformed into animals. The special effects, as you might guess, are quite primitive (with burning, for instance, depicted in the form of flames superimposed over people’s bodies) but generally do their job. I’ll also give the film props for its depth of feeling; as choppy and exploitive as it often is, the Buddhist convictions aired herein, and its redemptive arc, feel authentic and heartfelt.

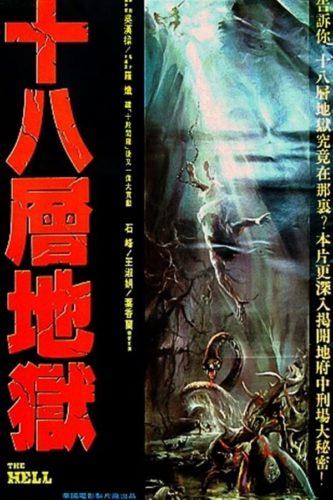

Chi Lo followed TEN COURTS OF HADES in 1982 with THE HELL (SHI BA CENG DI YU). Very much of a piece with the earlier film, it was an apparent attempt by Chi at covering the other conception of Diyu, as an 18 level affair (never mind that at least fifteen of those levels were left out).

Set in Feudal times, THE HELL again replicates the structure of JIGOKU in its fantasy-tinged opening half, featuring a swordsman whose sister is dragged off by Hell-spawned demons. The swordsman stays the night in a strange village that is in fact the portal to the underworld, which in place of the Yama Kings is lorded over by a cat-faced creature known as Master Ghost who likes to devour people whole. Upon descending into the inferno’s lower levels the swordsman meets up with his sister, and the two decide to search the Diyu for their deceased parents, being fortuitously protected from its demonic overseers by a trio of angelic rainbow-riding women.

Set in Feudal times, THE HELL again replicates the structure of JIGOKU in its fantasy-tinged opening half, featuring a swordsman whose sister is dragged off by Hell-spawned demons. The swordsman stays the night in a strange village that is in fact the portal to the underworld, which in place of the Yama Kings is lorded over by a cat-faced creature known as Master Ghost who likes to devour people whole. Upon descending into the inferno’s lower levels the swordsman meets up with his sister, and the two decide to search the Diyu for their deceased parents, being fortuitously protected from its demonic overseers by a trio of angelic rainbow-riding women.

They—and we—witness a lot of miscellaneous torment that once again is presented in extremely blunt fashion. People are dissolved in a lake of acid, eaten by a giant snake, burned, drawn and quartered, disemboweled, crushed, decapitated and impaled. At just 75 minutes the whole thing feels a bit scant, but it certainly can’t be said to overstay its welcome. Also, as with most East Asian fantasy fare of the period, it features a soundtrack comprised of tunes blatantly lifted from other movies; I noticed a couple cuts from the Tangerine Dream SORCERER soundtrack, and also (in the final scenes) the unmistakable CHARIOTS OF FIRE theme.

A RESCUE FROM HADES likewise hails from 1982. Directed by the late Liang Che-Fu (a prolific Taiwanese helmer whose final film this was), it’s not as exploitive or sensationalistic as TEN COURTS OF HADES or THE HELL, being far more stately overall. That’s not to say that Liang doesn’t include his share of outrages, such as UFO-like ghostly emanations that chase people around the mortal plane, footless shoes that walk on their own, and—once the protagonists enter the underworld—suitably horrific depictions of torture that include a woman having her skin ripped from her torso.

of outrages, such as UFO-like ghostly emanations that chase people around the mortal plane, footless shoes that walk on their own, and—once the protagonists enter the underworld—suitably horrific depictions of torture that include a woman having her skin ripped from her torso.

The story, such as it is, is set once again set in feudal times, and involves a virtuous monk looking to rescue his mother from the lowest level of hades. The Diyu on display here, incorporating the Ten Yama Kings, is far less invigorating than those of the previous films, but A RESCUE FROM HADES does deserve credit for its evocation of a number of obscure (to Western viewers, anyway) Buddhist practices, among them the Ghost Festival, during which the portals of Heaven and Hell are believed to be open, allowing people to pay homage to their deceased ancestors.

Great movies? Hardly, but TEN COURTS OF HADES, THE HELL and A RESCUE FROM HADES are standout examples of Asian exploitation, ideal for viewers wanting to know more about Buddhist mythology and also those in the mood for some straightforward Taiwanese trashola.