Here I’m going to look over Matthew Barney’s CREMASTER cycle. These five digitally lensed films, made over a nine year period, represent one of the most unique events in film history. Unique because they’ve captured the hearts, minds and wallets of the snootier-than-thou New York art crowd, who view them as bonafide objects d’art rather than proper films.

Here I’m going to look over Matthew Barney’s CREMASTER cycle. These five digitally lensed films, made over a nine year period, represent one of the most unique events in film history. Unique because they’ve captured the hearts, minds and wallets of the snootier-than-thou New York art crowd, who view them as bonafide objects d’art rather than proper films.

I don’t know much about the art world, but do know a little something about filmmaking, and so can attest that cinematically the CREMASTERS leave much to be desired. They’re dreamlike nonlinear swirls packed with all manner of grotesquerie that woefully lack the savvy of true masters of cinematic bizarrie like Alejandro Jodorowsky, David Lynch or Carmelo Bene. Of course, the fact that Barney identifies himself as an artist and not a moviemaker affords him a pat defense for his films’ shortcomings: it’s art, man!

And yet the CREMASTER flicks cannot be entirely dismissed. Any lover of the bizarre owes it to him or herself to see these films, or at least parts 2 and 3, as they contain many striking elements. Keep in mind, though, that your sole opportunity to do so is via the periodic revival screenings at art film venues, as the CREMASTER cycle will apparently never be distributed on commercial DVD.

Why? Because Barney sells limited edition DVDs of his films to art collectors for hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece (art just isn’t art, it seems, unless it’s really expensive) and uses the funds to finance his subsequent efforts. In this way he avoids the soul-crushing realities of independent film financing, and makes a comfortable living for himself in the process. That’s in direct contrast to Jodorowsky, who for over twenty years was unable to come up with sufficient funds to mount any new films, and Lynch, whose budgets tend to be laughably low.

But anyway, let’s take a look at the CREMASTER cycle. I’m going to review these films in the (dis)order they were made, which means I’ll begin with part 4 and continue with parts 1, 5, 2 and 3. I’ll also take a look at Barney’s DRAWING RESTRAINT 9, which is essentially CREMASTER 6.

begin with part 4 and continue with parts 1, 5, 2 and 3. I’ll also take a look at Barney’s DRAWING RESTRAINT 9, which is essentially CREMASTER 6.

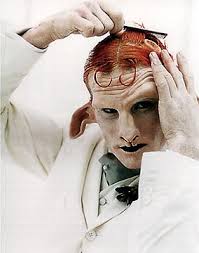

The cycle began back in 1994 with CREMASTER 4. Far more raggedy and homemade than the subsequent installments, it features a satyr-like dude (played by Matthew Barney himself) tap dancing in an ocean-bound cathedral, intercut with racecar drivers speeding down an open road. Eventually the satyr drops through a hole, ending up beneath the ocean floor in a slime-clogged maze of tunnels while tiny balls of goo ooze out of the racecar drivers’ pockets and a group of giggling women make their way toward the cathedral. It concludes with one of the most repellent images of all time: a man’s testicles squeezed and prodded with tongs!

CREMASTER 4 may lack the slickness of the later entries, but it’s an excellent introduction to the cycle, with its perverse debunking of masculine archetypes (the cremaster, FYI, is the muscle that hoists and lowers the testicles), faux-mythological imagery and overall love of the grotesque. It also features a lot of petroleum jelly, or Vaseline, which is one of Barney’s favored motifs.

CREMASTER 4 encapsulates all that’s good about the cycle—mainly a lot of striking imagery—as well as its core weakness: the editing, for which Barney has no evident skill or patience, simply letting his scenes drag on interminably. At least this film only runs 42 minutes, and so isn’t as punishing as some of the later entries.

CREMASTER 4 encapsulates all that’s good about the cycle—mainly a lot of striking imagery—as well as its core weakness: the editing, for which Barney has no evident skill or patience, simply letting his scenes drag on interminably. At least this film only runs 42 minutes, and so isn’t as punishing as some of the later entries.

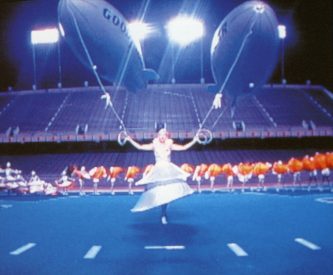

CREMASTER 1 followed in 1995. It had a far healthier budget than part 4, which is evident in the gaudy art direction. There’s even some CGI, which wasn’t easy (or cheap) to come by in ‘95. As I understand it, after finishing the previous film Barney first hit upon the idea of funding his future projects by selling the previous ones for hundreds of thousands of dollars, initially on VHS—yes, you read that right: back in the mid-nineties people actually shelled out upwards of $100,000 for a VHS.

This film centers primarily on a woman who lives under a table aboard a Good Year blimp. Using grapes that are always changing color (from red to yellow), she controls the actions of a double chorus line whose participants prance around a blue football field. Here we see the first depiction of the semicircle-with-a-line-through-it symbol that has become Matthew Barney’s trademark, amid imagery even more explicitly sexual than that of the preceding film. Overall, however, the segment is quite monotonous.

1997’s CREMASTER 5 is the least successful of these films. It stars Ursula Andress as an opera singer and Barney again, playing another  satyr-like mutant. This is the most pretentious entry, and so the most agonizing to sit through. The art direction is stunningly opulent and the images impeccably composed, which may in fact be the biggest problem: Barney, like many filmmakers before him, appears to have become overly caught up in the technical aspects at the expense of everything else. This may be “art” but it’s also a film, and pretty scenery does not a good film make

satyr-like mutant. This is the most pretentious entry, and so the most agonizing to sit through. The art direction is stunningly opulent and the images impeccably composed, which may in fact be the biggest problem: Barney, like many filmmakers before him, appears to have become overly caught up in the technical aspects at the expense of everything else. This may be “art” but it’s also a film, and pretty scenery does not a good film make

CREMASTER 2 arrived in 1999, and I feel it’s the best of the lot. It was the first CREMASTER film I saw (it being the first to play semi-commercially) and made enough of an impression that I was inspired to check out the rest of the cycle (whereas had I begun with parts 1 or 5 I probably wouldn’t have bothered).

It’s supposed to be about a meeting between Harry Houdini and mass murderer Greg Gilmore, but you’ll have to watch closely to discern that. What registers is—again—the imagery, with moments of such mind-bending strangeness that I honestly can’t be sure I didn’t dream them (an early scene in a gas station is particularly striking). Barney also includes enough evocatively creepy organ music, semi-pornographic interludes (a vagina with butterfly wings?) and (of course) Vaseline to almost make up for his standard non-editing.

But for all that I think Barney allows too much conscious thought to contaminate this otherwise impeccable dream-fest. American flags are a constant, along with various depictions of male aggression (a blaring death rocker, a man riding a bucking bronco, a monster truck), suggesting that Barney was attempting to make a statement about violence in American culture—although precisely what he was trying to say is anyone’s guess!

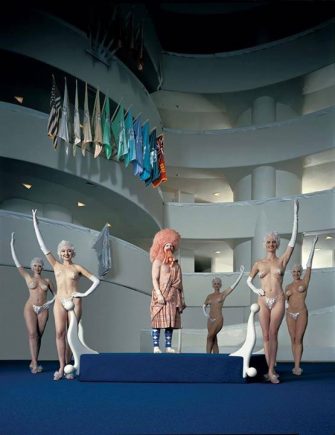

This brings us to the three-hour CREMASTER 3 from 2002, the most monumental installment by far. It contains an amazing succession of bizarre and horrific imagery: a giant tramping around a mossy seaside cliff, an emaciated stone woman dug up from the ground, a car slammed into repeatedly by other cars until only a tiny piece of crushed metal remains, a man (played by Barney) with a flower penis, a slimy wormlike thingee that emits a stream of goop, a bar covered in frozen Vaseline, rotting zombie horses pulling a cart down a racetrack, a guy scaling the interior of NYC’s Guggenheim Museum so he can romp with a satyr woman residing in the upper levels…yes, it’s that kind of movie!

This brings us to the three-hour CREMASTER 3 from 2002, the most monumental installment by far. It contains an amazing succession of bizarre and horrific imagery: a giant tramping around a mossy seaside cliff, an emaciated stone woman dug up from the ground, a car slammed into repeatedly by other cars until only a tiny piece of crushed metal remains, a man (played by Barney) with a flower penis, a slimy wormlike thingee that emits a stream of goop, a bar covered in frozen Vaseline, rotting zombie horses pulling a cart down a racetrack, a guy scaling the interior of NYC’s Guggenheim Museum so he can romp with a satyr woman residing in the upper levels…yes, it’s that kind of movie!

Had it been made with more finesse, CREMASTER 3 might have wound up a surreal masterwork on the order of Carmelo Bene’s OUR LADY OF THE TURKS, Jodorowsky’s HOLY MOUNTAIN or Lynch’s ERASERHEAD, but it’s not to be. Certain critics claimed that Barney’s editing skills here had improved since the earlier installments, but I saw no evidence of that. This film is every bit as formless and drawn-out as its predecessors, making one regret that it isn’t available on DVD (although Barney has deigned to release a small portion of it for home viewing called THE ORDER), as what CREMASTER 3 needs more than anything is a fast forward button.

That technically concludes my survey, but, as threatened, I’m going to finish with an quick overview of Matthew Barney’s DRAWING RESTRAINT 9 (2005). It looks and plays much like a CREMASTER flick, and was financed and distributed in a similar fashion—meaning you won’t be seeing it on DVD any time soon.

It’s another surreal slog in which Barney and his real life wife Bjork (who also composed the supremely irritating music score) play stowaways on a Japanese whaling ship. They get outfitted in wildly ornate Kabuki getup while on the deck of the ship crewmen pour untold gallons of Vaseline into a mold of that aforementioned semi-circle-with-a-line-through-it symbol. Said mold eventually hardens as the ship floods and the protagonists slowly slice each other up. That part’s eye-opening, to say the least, but for most of its interminable two-and-a-half-hour running time the film is maddeningly uneventful, making one realize that a large part of the CREMASTER flicks’ charm was their fecund grotesquerie, of which DRAWING RESTRAINT 9 contains very little.