It’s an unequivocal fact that 1986 was the pivotal year of the adult comic book renaissance. It was in ‘86 that three of the most influential comic series of the era, and indeed of all time—BATMAN: THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, WATCHMEN and MAUS—first made their presence known. Luckily for us, all three titles fit into the horror niche reasonably well, as do five more 1986 funny-book sagas that weren’t quite as monumental but are deserving of attention nonetheless (other important comics that commenced in 1986, but weren’t horror themed, include THE MAN OF STEEL, THE PUNISHER, CONCRETE and THE ‘NAM).

Now, thirty years later, let’s take a look back at these seminal comics and see how they’ve held up, starting with the first and most famous title of them all…

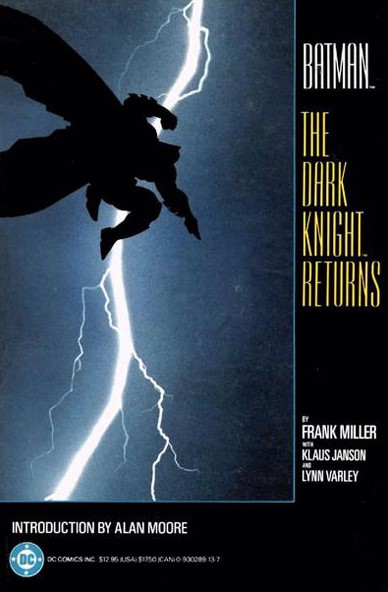

BATMAN: THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS

BATMAN: THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS

THEN: This four-issue DC miniseries provided the blueprint for the dark, brooding Batman we’ve come to know and love, as well as the breakout work of scripter/artist Frank Miller. Its portrayal of the “Dark Knight” as an aging vigilante in a nightmarish film noir netherworld was quite an eye-opener, as was Miller’s audacious visual design, which followed none of the set rules of traditional comic book paneling. Equally audacious was the layering-in of troubling real world elements like urban squalor, nuclear proliferation and media manipulation, and the fact that Batman actually gets into a fight with Superman—and wins!

NOW: This one, I’m afraid, has not held up especially well. To be fair, a large part of the reason is that most everything in THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS (such as the fight with Superman) has been done, and in many cases outdone, by subsequent Batman media. Nonetheless, it’s now painfully evident that Miller’s rather wobbly storytelling doesn’t match the brilliance of his visuals, nor pretentious dialogue like “We must not remind them that giants walk the Earth.” At least THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS still looks damn good.

WATCHMEN

THEN: This miniseries, about geriatric superheroes and their offspring attempting to subside in an alternate universe America, was like nothing else. Another DC triumph, WATCHMEN was a comic that actually functioned as great literature, being unerringly thoughtful and sophisticated in its approach while still delivering the down-and-dirty goods. Writer Alan Moore had done impressive work prior to WATCHMEN (on MIRACLEMAN and SWAMP THING, among others), but it was here that he really displayed his extraordinary capabilities. This is not to say that the world at large immediately took notice; as a teenager I was reprimanded for reading WATCHMEN during school hours, as it was apparently “just” a comic book.

NOW: Obviously this series, which is now known in the form of a standalone graphic novel, is a bit dated with its copious eighties references (a serious point of contention among viewers of the 2009 movie adaptation), and also the artwork of Dave Gibbons, which while impressive in its way is very much of its time in its simplistic, nuance-free coloring. Yet overall WATCHMEN holds up remarkably well, due in large part to the brilliance of Moore’s narrative construction and the cinematic sheen of the visuals (to gauge just well how it holds up compare WATCHMEN with Moore’s 1988 V FOR VENDETTA, to which time has not been kind). Also quite striking are the textual interludes that conclude each chapter, an element that has been widely imitated but never pulled off nearly as well as it was here.

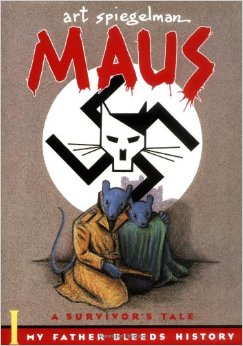

MAUS: MY FATHER BLEEDS HISTORY

THEN: I’ve always found the black and white MAUS, which premiered in 1986 after being serialized in the underground anthology RAW, a bit overrated, but it was quite a trailblazer. Back then depictions of the Holocaust were largely off-limits in popular culture (SCHINDLER’S LIST, let’s not forget, was nearly a decade in the future), which explains why writer-illustrator Art Spiegelman depicted this account of his father’s harrowing experiences in Nazi-occupied Poland with mouse-headed Jewish personages and cat-headed Nazis. Typical of the reaction was a back cover blurb from Newsweek stating “the very artificiality of its surface makes it possible to imagine the reality beneath.”

NOW: Amazingly, this volume, and its 1991 follow-up, have received an excess of academic praise, including the 1992 Pulitzer Prize. Furthermore, MAUS is now widely taught in schools, proving that a). There are no limits to what the mainstream now co-opts (as MAUS was initially considered subversive), and b). Peoples’ attitudes about the importance of comic books have changed dramatically since 1986 (see my above anecdote about getting caught reading WATCHMEN at school).

ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN

THEN: This outrageous Frank Miller scripted Epic Comics mini-series (spun off from the more mainstream-friendly DAREDEVIL) can be viewed as THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS’S wilder sibling. Packed with over-the-top mayhem and watercolor imagery by Bill Sienkiewicz that runs the gamut from exaggeratedly cartoony to overtly hallucinatory, ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN is a crazed stream-of-consciousness rendering of a babe assassin attempting to take down a demonically possessed presidential candidate. Unsurprisingly, it received a fraction of the popularity of THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, but did reportedly freak out the moral majority, with televangelists gleefully cataloging its evils to their slavering congregants.

NOW: Now that all the outrage has died down, ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN has been largely, and undeservedly, forgotten. It certainly didn’t help matters that Miller’s brooding 1991 follow-up ELEKTRA LIVES AGAIN was radically different in tone and style, and that a thoroughly bland Jennifer Garner headlined ELEKTRA movie appeared in 2005. Nonetheless, ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN fully retains its gloriously excessive edge.

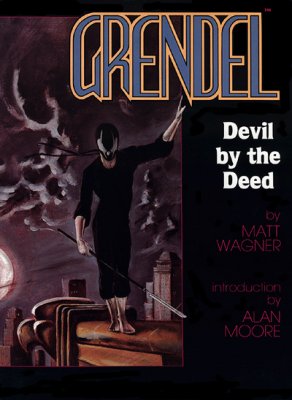

GRENDEL: DEVIL BY THE DEED

GRENDEL: DEVIL BY THE DEED

THEN: Like MAUS, this twisted saga, of a fencing enthusiast-turned-crime boss battling a (literal) wolf man, was initially published in piecemeal format (as a “backup story” in its creator’s earlier series MAGE) before appearing in a single volume in 1986. That volume came complete with an introduction by Alan Moore praising writer/illustrator Todd Wagner’s innovative layout that utilized blocks of text in place of the standard captions and dialogue balloons, combined with gorgeously rendered retro-leaning visuals that harkened back to the art deco era. The effect was closer to a series of painterly collages than traditional comic book pages, and made for an arrestingly unique volume.

NOW: Todd Wager’s text-and-illustration layout remains startling, although his clumsy storytelling and underdeveloped characterizations are far more evident now than they were back in ‘86, given that Wagner has since honed the skills that were in embryonic form here. Thus, DEVIL BY THE DEED is probably best read in conjunction with Wagner’s subsequent GRENDEL comics; luckily there now exist four omnibus editions, so doing that is not at all difficult.

DEMON WITH A GLASS HAND

THEN: This adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s OUTER LIMITS script “Demon with a Glass Hand” was the most popular of a late eighties series of DC issued graphic novels that fleshed out famous science fiction stories (others included Ray Bradbury’s FROST AND FIRE, Robert Bloch’s HELL ON EARTH and George R.R. Martin’s SANDKINGS). Its 1986 publication was quite timely, as the OUTER LIMITS episode in question had recently made the news for being part of a widely publicized plagiarism lawsuit brought by Ellison against the makers of THE TERMINATOR. Whatever influence it might have had on that film, DEMON WITH A GLASS HAND is a good story, about an amnesiac with a talking glass hand pursued through LA’s Bradbury building by a band of gold medallion-wearing creeps, and was nicely adapted by Marshall Rogers with some seriously outré angles and an impressively noirish color scheme.

NOW: This book remains a good-looking piece of work that’s superior to the OUTER LIMITS episode that inspired it (which didn’t follow Ellison’s script to the letter, unlike this book). The biggest problem from a modern standpoint is that at just 48 pages it’s far too short, being closer to a longish comic book issue than the graphic novel that was promised.

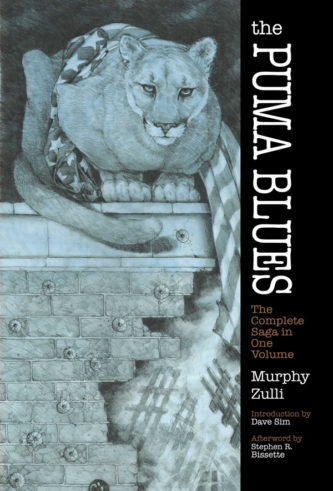

THE PUMA BLUES

THEN: This superbly drafted environmental screed-cum-apocalyptic nightmare was for much of its thirty year existence the most elusive title on this list. THE PUMA BLUES, which had a downright torturous distribution history, was widely acclaimed by the lucky few who managed to track down its complete run (which began in ‘86 and lasted roughly three years), but doing so was no easy task! It was an impressive work, in any event, with a strikingly poetic narrative, stunningly drafted black and white artwork and an ecological conscience that was unprecedented in the don’t-worry-be-happy era.

NOW: It wasn’t until 2015, when the entire series was issued in a hardcover omnibus by Dover, that it was possible (for me at least) to properly assess THE PUMA BLUES’S artistic merits. Its obscurity ensured that any influence it may have had on subsequent media was essentially nil, although the series received rapturous praise from industry heavyweights like Alan Moore, Stephen R. Bissette and Neil Gaiman, so it clearly had some impact.

SALOME

THEN/NOW: This isn’t the only comic book treatment of Oscar Wilde’s SALOME (it was also adapted, quite ably, by P. Craig Russell around the same time), but it is the best. For that matter, I’d say British artist David Shenton’s rendering of SALOME is one of the most visually innovative graphic novels I’ve ever laid eyes on, with a dazzlingly bold color palette and freeform layout that remain as impressive today as they did thirty years ago. Tragically, however, this eye-popping work never received much attention of any sort, then or now. Here’s hoping this mini-review will be the first step in a long overdue appreciation!