France’s Roland Topor (1938-1997) was a veritable genius of perverse and surreal literature. He is admittedly better known for his paintings and drawings, which have been collected in several books (including the landmark avant-garde collection AN ANECDOTED TOPOGRAPHY OF CHANCE), as well as his participation in the Panic Movement (Mouvement panique), which Topor created in 1962 together with fellow Paris-based provocateurs Fernando Arrabal and Alejandro Jodorowsky, and also his film work–consisting of visual design on the Rene Laloux animated films LES TEMPS MORTS (1964), LES ESCARGOTS (1965) and LA PLANETE SAUVAGE (1973), acting in Dusan Makavajev’s SWEET MOVIE (1974) and Werner Herzog’s NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE 1979), and co-scripting the perverted puppet pastiche MARQUIS (1989). But it’s his prose that is of interest here, even if precious little of it is available in English.

France’s Roland Topor (1938-1997) was a veritable genius of perverse and surreal literature. He is admittedly better known for his paintings and drawings, which have been collected in several books (including the landmark avant-garde collection AN ANECDOTED TOPOGRAPHY OF CHANCE), as well as his participation in the Panic Movement (Mouvement panique), which Topor created in 1962 together with fellow Paris-based provocateurs Fernando Arrabal and Alejandro Jodorowsky, and also his film work–consisting of visual design on the Rene Laloux animated films LES TEMPS MORTS (1964), LES ESCARGOTS (1965) and LA PLANETE SAUVAGE (1973), acting in Dusan Makavajev’s SWEET MOVIE (1974) and Werner Herzog’s NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE 1979), and co-scripting the perverted puppet pastiche MARQUIS (1989). But it’s his prose that is of interest here, even if precious little of it is available in English.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised at the paucity of English translations of Topor’s written work. His worldview, after all, was as mordant as that of just about anyone who’s ever lived, with a comedic streak of the darkest imaginable hue.

In his memoir THE DANCE OF REALITY, Jodorowsky describes a dream in which he met a post-death Roland Topor, drawing happy pictures after “having passed through this mystery of death that had prevented him from appreciating life.” That tendency is evident in the listing entitled “100 Good Reasons to Kill Myself Right Now,” (the English version of which can be found here), written near the end of Topor’s life. Those reasons include “I’ll no longer dread the millennium,” “There’s nothing left to do,” “To feast on the exquisite blood of young women, once I’m a vampire” and, finally, “Because I’ve got 1,000 good reasons to hate myself.”

Of Topor’s fiction, some have opined that it consists of little more than elaborations on the surreal imagery of his  artwork. His first and greatest novel THE TENANT (LA LOCATAIRE CHIMERIQUE), published in 1964 (and translated into English by Francis K. Price two years later), belies that claim.

artwork. His first and greatest novel THE TENANT (LA LOCATAIRE CHIMERIQUE), published in 1964 (and translated into English by Francis K. Price two years later), belies that claim.

THE TENANT relates the fiendishly compelling account of Trelkovsky, a mousy man who moves into an apartment building whose other tenants seem excessively nosy. He could just be paranoid, but as far as the reader is concerned Trelkovsky’s neighbors are indeed up to no good, scheming to literally turn him into his room’s former occupant: a disturbed young woman who committed suicide. Trelkovsky desperately tries to hold onto his identity, but finds himself dressing in ladies’ clothing and assuming various womanly affectations.

It’s a testament to Topor’s skilled prose, related in disarmingly rational and straightforward fashion, that this bizarre tale is so convincing. It also succeeds in probing the depths of suspicion, paranoia and identity in a story that begins as an unassuming potboiler and ends up one of the most harrowing tales of horror I’ve ever experienced, all in the space of a fast and compact 138 pages. The Roman Polanski directed movie version of THE TENANT, released in 1976, is a strong and highly faithful adaptation, but it’s in this novel that the material finds its fullest expression.

More befitting of the above-quoted dismissal of Topor’s fiction is JOKO’S ANNIVERSARY, an exercise in free-form absurdism with little use for things like logic or character development. It excels, however, in audacity and feverish invention. Joko is a working stiff who on his way to work one morning has an old man climb onto his back, desiring a ride. Quite a few other folks also want back rides, and before long Joko is making a decent income ferrying people around. One day, however, Joko develops a strange infection that causes his fare of the day to stick to him.

More befitting of the above-quoted dismissal of Topor’s fiction is JOKO’S ANNIVERSARY, an exercise in free-form absurdism with little use for things like logic or character development. It excels, however, in audacity and feverish invention. Joko is a working stiff who on his way to work one morning has an old man climb onto his back, desiring a ride. Quite a few other folks also want back rides, and before long Joko is making a decent income ferrying people around. One day, however, Joko develops a strange infection that causes his fare of the day to stick to him.

Whatever it is that Joko has, it’s obviously extremely virulent, as six more people become unwittingly stuck to his back. All of Joko’s newfound companions are rude, selfish and murderous individuals who act out their frustrations by brutalizing Joko and dismembering his two sisters. Joko’s parents retaliate with equal ferocity, leaving everyone dead but Joko. It turns out, however, that his problems are only beginning, as now the souls of his companions are loose within him, and aren’t shy about using his body to carry out all manner of depraved acts!

At a scant 122 pages, JOKO’S ANNIVERSARY is more an extended outline than a proper novel, complete with names above dialogue blocks to denote the speaker (which reaches a comedic pitch in the final third, when Joko becomes possessed and so shares credit with the other speakers). One could take this as a Kafkaesque exploration of the human condition or just a sick joke taken too far; in either case it’s a curiously memorable account that’s hilarious and repellent in equal measure.

Of Topor’s shorter fiction, the sole English language compilation is TOPOR: STORIES AND DRAWINGS, which  appeared in 1968. As translated by Margaret Crosland and David Le Vay, it provides a full display of Topor’s brand of macabre absurdity, as well as his unfortunate shortcomings as a prose stylist.

appeared in 1968. As translated by Margaret Crosland and David Le Vay, it provides a full display of Topor’s brand of macabre absurdity, as well as his unfortunate shortcomings as a prose stylist.

At their best Topor’s stories transcend their surface-level gross-out humor. An example would be “The Blue-Eyed Boy,” about a pathologically timid man’s attempt at asking his boss for a raise, and the outrageous and ultimately horrific upheavals that result. It stands as a potent exploration of social anxiety, in which respect it recalls THE TENANT. Of a similar hue is “Wrong Number,” about a shy man who gets a reprieve from his solitary life–or so he thinks–when he installs a telephone in his apartment. The resulting outrages are sufficiently uproarious and grotesque, but also quite smart in their explication of the paranoia and apprehension that gradually overtake the protagonist.

Some of the stories are little more than half-page sketches, such as “To Godliness,” about what occurs when a heavily made-up girl washes her face. Others are decidedly lacking in maturity: see “Christmas Story,” about a gay rapist (indicated by the fact that he slurs his words) who dresses like Santa Claus in a tale that reads like a thirteen year old’s attempt at shocking his elders.

The lone English language example of Topor’s playwriting can be found in the Barbra Wright translated LEONARDO WAS RIGHT (1976/78), which has been reported to empty many a theater. It’s a French farce, a format that has never resonated much with me, although this one is of interest due to its sheer outrageousness.

The lone English language example of Topor’s playwriting can be found in the Barbra Wright translated LEONARDO WAS RIGHT (1976/78), which has been reported to empty many a theater. It’s a French farce, a format that has never resonated much with me, although this one is of interest due to its sheer outrageousness.

The subject is shit, as experienced by Alain Moreau, a police officer, and his wife Colette, a “petite bourgeoise who would like to become a grande one.” The madness begins when the Moreaus’ toilet becomes clogged just as the Boulins, a young cop and his wife, arrive for a weekend stay. It certainly doesn’t help matters that Guy Boulin has diarrhea, or that as the weekend stretches on several errant turds turn up around the Moreaus’ house. Who is the culprit? Guy? Collette? Alain’s trouble-making son Robert? His Swedish maid Inge? All of the above? And where the Hell is the plumber Alain called to fix his crapper?

Obviously one’s reaction to LEONARDO WAS RIGHT depends on his or her tolerance level for unabashed scatology, but it is an attention-getter without question. The title, BTW, refers to a quote by Leonardo Da Vinci that states “The only thing some people will leave behind them is overflowing latrines.”

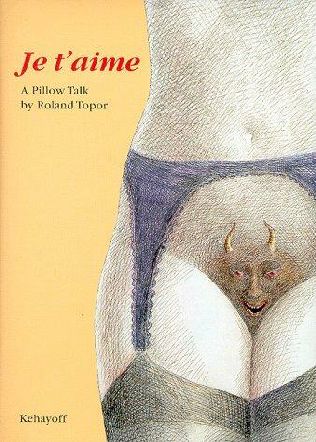

Finally we have the unclassifiable booklet JE T’AIME (L’AMOUR A VOIX HAUTE) from 1998/99. Translated by  Michael Knight, it’s a “Pillow Talk” consisting of short verbal outbursts collected, Topor claims, from a lifetime’s worth of sexual encounters. They range from “I love you,” “Keep it up,” “My pubic hair got caught” and “Are you frigid?” to more esoteric offerings like “Tell your parrot to keep his mouth shut,” “You’re bleeding!” and “Take off your gas mask(!).”

Michael Knight, it’s a “Pillow Talk” consisting of short verbal outbursts collected, Topor claims, from a lifetime’s worth of sexual encounters. They range from “I love you,” “Keep it up,” “My pubic hair got caught” and “Are you frigid?” to more esoteric offerings like “Tell your parrot to keep his mouth shut,” “You’re bleeding!” and “Take off your gas mask(!).”

I’m not entirely sure these sayings are “essential to our understanding of the human animal,” as Topor maintains in his forward, but they do make for a charming and enjoyable volume, augmented by Topor’s inimitable sexually tinged artwork.

Further Topor prose books include the mock cookbook LA CUISINE CANNIBALE and the fictional volumes CAFÉ PANIQUE, JOURNAL IN TIME and PORTRAIT EN PIED DE SUZANNE, all of which remain untranslated. Let’s hope that situation changes, and soon.