It’s been claimed that a third of the world’s most depressing films emerge from Canada and, having viewed many a Canadian film, I believe it. Check out the following ten films, comprising the latest edition of the Toronto International Film Festival’s Best Canadian Films listing (taken by Canuck cinema mavens as the definitive such ranking), which are all profoundly depressing. These films, in other words, are diametrically opposed to the type of faux-inspirational Oscar bait Hollywood excretes each year.

Understand: these are prestige items, so you won’t find PORKY’S, SCREWBALLS or FUNERAL HOME (purebred Canadian products all) included in this line-up. Nor, surprisingly, are Canadian classics like Bruce McDonald’s HARD CORE LOGO, John Paizs’s CRIME WAVE or Micheline Lanctot’s SONATINE, all of which deserve a place on this list—a list that, as you’ve probably gathered, I thoroughly disagree with in terms of choice and ranking, the #1 entry in particular..

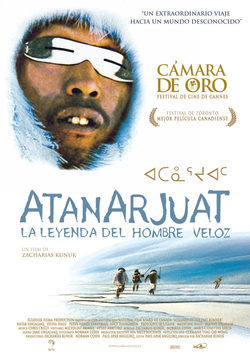

1. ATANARJUAT: THE FAST RUNNER

1. ATANARJUAT: THE FAST RUNNER

Sorry, but I don’t understand this selection at all. The world’s first and only Eskimo-sploitation movie, 2001’s ATANARJUAT is a wildly overrated reverie about the lives of the Inuktitut people who reside in the frozen wastes of Northern Canada.

The film definitely feels authentic in its presentation of the bizarre (to us, anyway) customs of its subjects, but the story, involving a guy’s banishment from his tribe by an evil force, is utterly pedestrian. It doesn’t help that most of this nearly 3-hour, digitally shot film is erratically paced and dramatically muddled. I realize my tastes are eccentric, but I say it’s a fact that this is not—repeat, not-–the greatest Canadian film of all time.

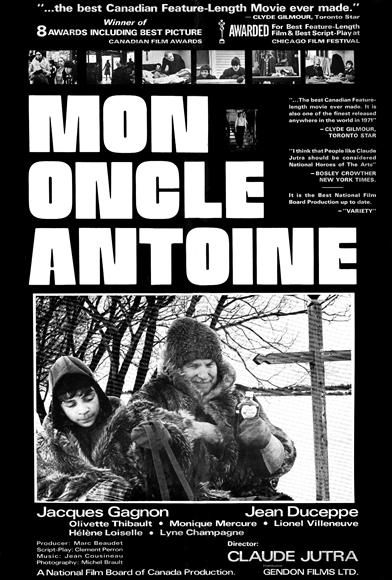

2. MON ONCLE ANTOINE

This was a shocker, as this 1971 film usually always nabs the number one spot. I’m not sure why that  changed in 2015, although I’m certain MON ONCLE ANTOINE won’t be regaining its former prestige any time soon (or ever) due to 2016 allegations that the late Claude Jutra, its widely renowned director, was an unrepentant pedophile. This has led to a major reassessment of his exalted place in Canadian cinema (all the awards, street names, etc. bearing Jutra’s name have been remonikered), as well as the standing of this film—and, admittedly, MON ONCLE ANTOINE does have a different resonance now than it did previously, as its protagonist, a thirteen year old boy, was apparently the preferred age and gender of Jutra’s sexual conquests.

changed in 2015, although I’m certain MON ONCLE ANTOINE won’t be regaining its former prestige any time soon (or ever) due to 2016 allegations that the late Claude Jutra, its widely renowned director, was an unrepentant pedophile. This has led to a major reassessment of his exalted place in Canadian cinema (all the awards, street names, etc. bearing Jutra’s name have been remonikered), as well as the standing of this film—and, admittedly, MON ONCLE ANTOINE does have a different resonance now than it did previously, as its protagonist, a thirteen year old boy, was apparently the preferred age and gender of Jutra’s sexual conquests.

Yet there’s a reason the film is so highly ranked. Quite simply: it’s damn good, with the poetic realism so integral to Quebec cinema fully in evidence, as well as the bleakness. In the universe of Canadian film “coming of age” means, essentially, facing up to the fact that the world is a horrible place, which manifests itself here in the protagonist’s climactic realization that his much-admired uncle Antoine is in fact a worthless drunk. There’s also a troubling dead kid subplot and an overall atmosphere of grit and depression that, despite some technical shoddiness (such as a horrendously unconvincing rear projection effect), is achieved with great beauty and poetic verve. The greatest Canadian film ever made? Not quite, but MON ONCLE ANTOINE is definitely up there.

3. THE SWEET HEREAFTER

Here’s a choice I just don’t get. Sure, Atom Egoyan’s SWEET HEREAFTER, from 1997, is a good movie, but the third greatest Canadian film ever? Hardly! I much prefer Egoyan’s previous feature EXOTICA (1994), a far more daring and unprecedented achievement, in my view, than the comparatively conventional SWEET HEREAFTER—which pivots on a courtroom drama in the wake of a catastrophic bus accident that has devastated a small town. Yes, it’s another bleak and hopeless Canadian drama with an ending, involving one character lying on the stand and another getting falsely implicated in the tragedy, that’s questionable on many levels.

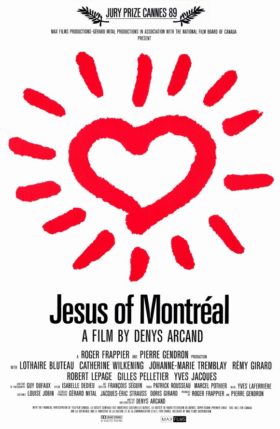

4. JESUS OF MONTREAL

4. JESUS OF MONTREAL

A worthy entry! 1989’s JESUS OF MONETREAL is a great film, possibly even a masterpiece, that sees Quebec’s Denys Arcand exploring issues of faith and divinity in the modern world. Arcand does this in a witty and intelligent manner far removed from the simplistic evangelical films that have become so prevalent in recent years.

In essence JESUS OF MONTREAL is about an actor (Lothaire Bluteau) playing Jesus in a modern-day passion play who comes to take his role a little too seriously, but there’s far more to the film, including an ending that, in keeping its Canadian pedigree, is notably grim.

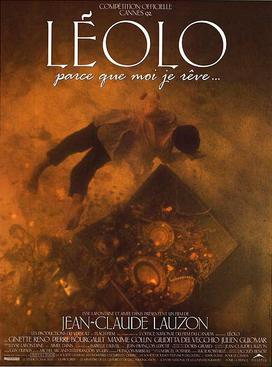

5. LEOLO

The fifth greatest Canadian film? I’d move this one up–to the number one position! The late Jean-Claude Lauzon’s  1992 LEOLO is easily the most daring and masterful film on this list, a tender, gruesome and cinematically dazzling concoction that far outshines the aforementioned MON ONCLE ANTOINE, and just about everything else, in the category of coming-of-age themed cinema. It boasts imagery worthy of Fellini and an impeccably calibrated soundtrack containing songs by Tom Waits and the Rolling Stones, and (of course) an extremely downbeat trajectory. LEOLO is certainly the only film I know of that contains impregnation by a tomato, an imaginary Italy situated in the slums of Quebec, synchronized shitting, extreme weight lifting, feline rape, masturbation with a chunk of liver and pre-pubescent suicide. Yes, it’s that kind of movie!

1992 LEOLO is easily the most daring and masterful film on this list, a tender, gruesome and cinematically dazzling concoction that far outshines the aforementioned MON ONCLE ANTOINE, and just about everything else, in the category of coming-of-age themed cinema. It boasts imagery worthy of Fellini and an impeccably calibrated soundtrack containing songs by Tom Waits and the Rolling Stones, and (of course) an extremely downbeat trajectory. LEOLO is certainly the only film I know of that contains impregnation by a tomato, an imaginary Italy situated in the slums of Quebec, synchronized shitting, extreme weight lifting, feline rape, masturbation with a chunk of liver and pre-pubescent suicide. Yes, it’s that kind of movie!

6. GOIN’ DOWN THE ROAD

Another selection I just don’t get. GOIN’ DOWN THE ROAD, from 1970, was apparently the impetus for the “Pessimistic Social Realism” brand of cinema that gripped Canada during the seventies (resulting in bummers like WEDDING IN WHITE and PAPERBACK HERO). The film was Canada’s answer to successful Hollywood fare of the time like EASY RIDER and MIDNIGHT COWBOY, although GOIN’ DOWN THE ROAD makes those films look positively warm and sunny by comparison. The loser protagonists of MIDNIGHT COWBOY at least got to experience the New York party scene before bottoming out, whereas the heroes of GOIN’ DOWN THE ROAD find themselves mired in a succession of dead-end jobs, a loveless marriage, and, finally, petty crime. Those “heroes” are two high school drop-outs who travel from Nova Scotia to Toronto in search of fame and fortune, which, needless to say, they don’t find.

Director and co-writer Don Shebib (the other scripter was future exploitation impresario William Fruet) provides a vividly naturalistic depiction of downtown Toronto circa 1970, but there’s a fine line between documentary realism and outright scuzziness, and I think Shebib might have stepped right over it.

7. DEAD RINGERS

7. DEAD RINGERS

For decades David Cronenberg’s oeuvre went unrepresented on these listings. The most common excuse for Cronenberg’s absence was that voters had trouble choosing between VIDEODROME and DEAD RINGERS; well, it seems they’ve finally managed to make the better-late-than-never choice, with 1988’s DEAD RINGERS winning out. It is indeed one of Cronenberg’s standout films, and fully deserving of being placed in a best Canadian films ranking (as, I’d argue, are VIDEODROME, THE FLY and CRASH).

If by some odd chance you’re unfamiliar with this bizarre, beautiful and (of course) depressing film, it concerns the disintegration of twin gynecologists and—perhaps more importantly—the relentlessly cold and antiseptic world they inhabit. From a technical standpoint the movie is flawless, with the cinematography by Peter Suschitzky, art direction by Carol Spier and music by Howard Shore all perfectly complimenting Cronenberg’s vision. Of course, none of that would matter were it not for the lead performances of Jeremy Irons, who manages to create two very distinct characters who nonetheless have far too much in common. And then there are the excellent, non-showy special effects that have Irons seamlessly playing off himself in scene after amazing scene.

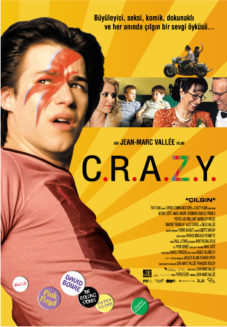

8. C.R.A.Z.Y.

This 2005 release is yet another coming-of-age downer, albeit one that’s slightly more upbeat than the previous entries. C.R.A.Z.Y.’s first third feels like a kinder, gentler LEOLO in its broadly comedic depiction of an eccentric young boy attempting to find his way amid an even more eccentric family in the 1950s. Things get considerably darker in the later sections, in which the boy grows into a sexually confused, disenchanted young man as his family falls apart around him. It’s all quite affecting, albeit a bit too slick overall, not to mention overlong.

a kinder, gentler LEOLO in its broadly comedic depiction of an eccentric young boy attempting to find his way amid an even more eccentric family in the 1950s. Things get considerably darker in the later sections, in which the boy grows into a sexually confused, disenchanted young man as his family falls apart around him. It’s all quite affecting, albeit a bit too slick overall, not to mention overlong.

Why this film, an early effort by the future helmer of DALLAS BUYER’S CLUB and WILD, was chosen as the eighth greatest Canadian movie while similarly themed, and worthier, Canuck films like GOOD RIDDANCE, THE OUTSIDE CHANCE OF MAXIMILLIAN GLICK and THE SEX OF THE STARS were ignored by TIFF’s voters is something I’ll never understand.

9. MY WINNIPEG

It’s good to see the incomparable Guy Maddin represented here with 2007’s MY WINNIPEG, which is indeed one of his better films. It’s at once an eccentric autobiography, a nostalgic travelogue, a goofy old movie parody and a cockeyed exercise in sheer weirdness. Its protagonist is Maddin himself, who as the film opens decides to leave his native Winnipeg behind (again!), but it seems the place holds far too many memories for him. Maddin tries to extricate himself from Winnipeg by having actors reenact scenes from his childhood, lorded over by his beauty salon worker mother and haunted by the premature death of his hockey coach father.

Along the way he gives us a highly esoteric mini-tour of the city, most notably an iconic department store and hockey rink, both of which have been torn down. Maddin includes documentary footage of these landmarks before and after demolition, alongside the type of deliberately archaic, mock silent movie styling in which he tends to specialize. The two elements might seem to make for a clash, yet Maddin somehow gets them to work together beautifully in a film that follows its own inscrutable muse.

10.(tie) STORIES WE TELL

10.(tie) STORIES WE TELL

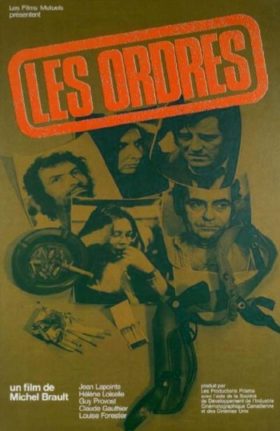

LES ORDRES

These days every best-of listing has to have a politically correct choice, hence the inclusion of 2012’s STORIES WE TELL. That it was directed by a woman is crucial in this regard, as is the fact that said woman happens to be actress/liberal activist Sarah Polley, who in Canadian film circles is treated in a downright saintly manner. This would explain why STORIES WE TELL, a documentary about Polley’s family background, never bothers explaining who she is, why she’s making the film or why we should care—clearly, the fact that she’s Sarah Polley renders all those questions nil, as evinced by the orgasmic reaction so many critics had to STORIES WE TELL (and most everything else Polley has done).

The film, however, is mediocre at best, mixing staged super 8mm footage with recollections by various family members. The idea (according to the reviews I’ve read) was to show how the various narratives spun by this “family of storytellers” diverge from and  contradict one another, yet it seemed to me those narratives all seemed pretty uniform and complimentary—and also, surprisingly given that everyone here is an apparent storyteller, quite rambling and dull overall.

contradict one another, yet it seemed to me those narratives all seemed pretty uniform and complimentary—and also, surprisingly given that everyone here is an apparent storyteller, quite rambling and dull overall.

1974’s LES ORDRES is something else entirely. This “docufiction” is fully deserving of its inclusion on this listing (although it should be ranked much higher), being one of the most powerful and uncompromising political dramas to emerge from inside or out of the Great White North. It depicts what took place during the 1970 “October Crisis” in Quebec, in which the War Measures Act was invoked in the wake of some high-profile kidnappings, and hundreds of law-abiding folk were wrongfully arrested. Director Michel Brault dramatizes a portion of that round-up without political sloganeering or weepy melodrama, capturing an unshowy sense of documentary realism in what can be taken as a real-life variant on Kafka’s THE TRIAL—and a film that, despite being over 40 years old, couldn’t be more timely.