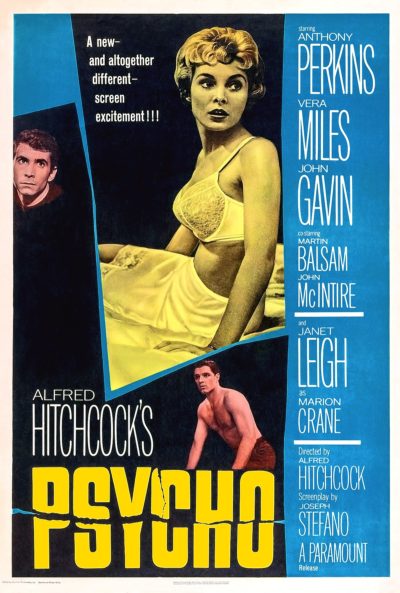

Here we’re going to look at what is very likely the most iconic and widely discussed horror movie of all time: Alfred Hitchcock’s PSYCHO. Certainly there’s not a lot I can say about PSYCHO that hasn’t already been said or written about it. The film is the subject of several books—including a 1992 comic book adaptation, ALFRED HITCHCOCK AND THE MAKING OF PSYCHO by Stephen Rebello and a personal reminiscence of the production by the film’s star Janet Leigh—and countless more reviews, articles and retrospectives.

Here we’re going to look at what is very likely the most iconic and widely discussed horror movie of all time: Alfred Hitchcock’s PSYCHO. Certainly there’s not a lot I can say about PSYCHO that hasn’t already been said or written about it. The film is the subject of several books—including a 1992 comic book adaptation, ALFRED HITCHCOCK AND THE MAKING OF PSYCHO by Stephen Rebello and a personal reminiscence of the production by the film’s star Janet Leigh—and countless more reviews, articles and retrospectives.

The film is the subject of several books—including a 1992 comic book adaptation, ALFRED HITCHCOCK AND THE MAKING OF PSYCHO by Stephen Rebello…

PSYCHO all-but invented the slasher and psychological thriller movie tropes, and established new levels of onscreen candor in its depictions of star Janet Leigh stripped down to her undies and a toilet (apparently the first time such an object had been seen in a movie), and also the show-stopping shower murder scene that according to film critic/historian David Thomson was “perhaps the most violent passage until then in American film.” It also changed movie exhibition forever: before PSYCHO’S 1960 release it was commonplace for audiences to wander in and out of movies whenever they felt like it, but with PSYCHO Hitchcock made it a rule that theaters had to be cleared at the end of each showing—which is how it’s been ever since.

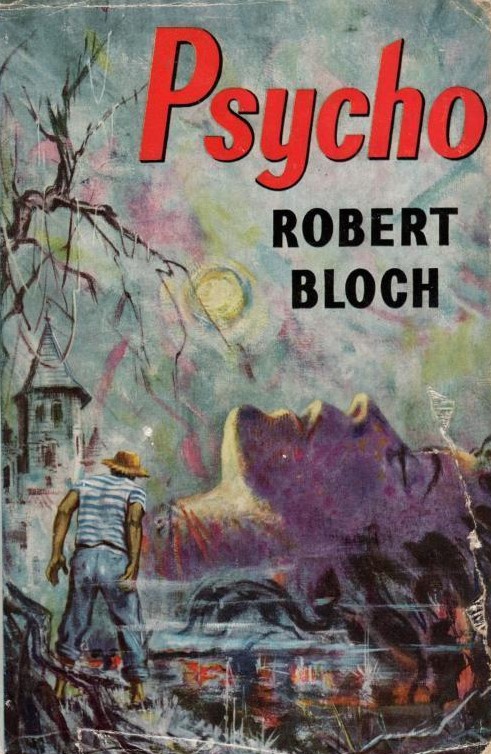

So iconic is PSYCHO that its stars Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh are forever tied to it (as, for that matter, is Leigh’s daughter Jamie Lee Curtis, whose association with the film doubtless had some bearing on her being cast in HALLOWEEN). The same can be said for its screenwriter Joseph Stefano and the author of its source novel, the late Robert Bloch—who it seems is fated to be known forevermore as “the author of PSYCHO”—and also the real-life inspiration for its horrors, the Wisconsin-based serial killer Ed Gein, a.k.a. “The Original Psycho.” For that matter, Alfred Hitchcock himself was never able to escape the imposing shadow of PSYCHO.

So iconic is PSYCHO that its stars Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh are forever tied to it (as, for that matter, is Leigh’s daughter Jamie Lee Curtis, whose association with the film doubtless had some bearing on her being cast in HALLOWEEN).

It’s no accident that Hitchcock’s post-1960 films were more overtly horrific than those that came before, with lighthearted 1950s-era entertainments like TO CATCH A THIEF and NORTH BY NORTHWEST giving way to the bleak and brooding likes of THE BIRDS and FRENZY. Many of Hitchcock’s PSYCHO follow-ups, furthermore, were marked by graphic torture/murder set pieces, including the climactic bird attack in THE BIRDS, the protracted oven killing in TORN CURTIN and the equally protracted strangulation in FRENZY.

Hitchcock’s own attitude toward PSYCHO is summed up by his admission that “I don’t care about the subject matter; I don’t care about the acting; but I do care about the pieces of film and the soundtrack and all the technical ingredients that made the audience scream.” That would certainly explain the film’s mechanical air, and also its severely protracted narrative. PSYCHO’S construction is impressive, certainly, but the problem is that nowadays, with the shock value having long since worn off, it’s that mechanical air that remains.

the acting; but I do care about the pieces of film and the soundtrack and all the technical ingredients that made the audience scream.” That would certainly explain the film’s mechanical air, and also its severely protracted narrative. PSYCHO’S construction is impressive, certainly, but the problem is that nowadays, with the shock value having long since worn off, it’s that mechanical air that remains.

PSYCHO’S construction is impressive, certainly, but the problem is that nowadays, with the shock value having long since worn off, it’s that mechanical air that remains.

A comparison can be made with Michael Powell’s PEEPING TOM, a psycho-thriller that likewise premiered (in England) in 1960, albeit to far less rapturous reception than PSYCHO. The reaction to PEEPING TOM, in fact, was downright hostile, and effectively ended Powell’s once-distinguished career. Unlike PSYCHO, PEEPING TOM provided a troubling look into the disturbed psyche of its psychopathic protagonist, and also the nature of the filmmaking impulse; it’s no accident that the protagonist in question utilized a spiked camera tripod leg in his killings. PSYCHO, by contrast, provides a skilled but strictly surface-level thrill ride.

That surface-level aesthetic extends to the celebrated 45 second shower scene, with which you’re probably familiar even if you haven’t actually seen PSYCHO. Audiences in 1960 apparently thought they saw far more than is actually shown, and many critics continue to insist that’s the case. Sorry, but to modern audiences familiar with the type of rapid fire montage editing that characterizes the sequence it’s painfully evident that the stabbing knife never actually makes contact with Janet Leigh’s flesh, and that the trickles of “blood” (actually chocolate syrup) seen running down the drain are noticeably scant.

What is most surprising about PSYCHO all these years later is that despite its outsized reputation it’s an extremely contained and low key affair–a “small” movie in every sense of the word. Only two people die in the course of the film, an unacceptably low ratio in today’s splatter-verse, and the cut-rate scenery is more redolent of fifties-era episodic television than a feature film (and no wonder, as the budget was quite low and the crew taken from that of ALFRED HITCHCOCK PRESENTS).

…despite its outsized reputation it’s an extremely contained and low key affair–a “small” movie in every sense of the word.

You likely know the story: the luscious young secretary Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) has just finished banging her lover in a Phoenix hotel room. Back at work her boss gives her $40,000 to deposit in a bank, but instead of depositing the money Marion makes off with it, embarking on a marathon drive to California. That night, during a freak rainstorm, Marion pulls in at an unassuming motel run by Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), an odd young man who lives with his domineering mother in a forbidding old house overlooking the motel. Marion has dinner with Norman, who turns out to have major issues with his mother…who stabs Marion to death in the scene that gave PSYCHO its charge.

You likely know the story: the luscious young secretary Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) has just finished banging her lover in a Phoenix hotel room. Back at work her boss gives her $40,000 to deposit in a bank, but instead of depositing the money Marion makes off with it, embarking on a marathon drive to California. That night, during a freak rainstorm, Marion pulls in at an unassuming motel run by Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), an odd young man who lives with his domineering mother in a forbidding old house overlooking the motel. Marion has dinner with Norman, who turns out to have major issues with his mother…who stabs Marion to death in the scene that gave PSYCHO its charge.

Norman, being the dutiful son he is, takes pains to clean up his mother’s mess, spending the remainder of the night and much of the following day mopping up the blood and disposing of Marion’s corpse in the trunk of her car, which is interred in a nearby swamp. Then Arbogast, an extremely thorough private investigator, shows up at the motel in search of Marion—and becomes Ms. Bates’ second victim. Arbogast is followed by Marion’s sister Lila and Marion’s lover Sam, which further inflames the situation with Norman and his mother. There’s a surprise at the end, but I’m sure you know what it is; I don’t think I need add a spoiler alert in proclaiming that Norman Bates’ mother is in fact long dead, and Norman, being psychotic, has taken on her personality.

The gambit of having the apparent leading lady killed off 47 minutes into the film was quite audacious, but it weakens the drama. This is to say that Janet Leigh is so engaging the film never overcomes her loss, with the alternating protagonists of the second half—Martin Balsam as the private investigator, Vera Miles as Lila and John Gavin as Sam—making for poor substitutes. Anthony Perkins’ turn as Norman Bates, on the other hand, has become legendary, so much so that Perkins essentially replayed the role in subsequent films like THE FOOL KILLER, HOW AWFUL ABOUT ALLAN, CRIMES OF PASSION and EDGE OF SANITY. There’s a reason for that.

This is to say that Janet Leigh is so engaging the film never overcomes her loss, with the alternating protagonists of the second half—Martin Balsam as the private investigator, Vera Miles as Lila and John Gavin as Sam—making for poor substitutes.

There’s also a reason Robert Bloch’s 1959 source novel has endured. It contains everything that’s good about the flick (despite screenwriter Joseph Stefano’s claim that he invented the structure himself), including Norman Bates’ immortal utterance “we all go a little mad sometimes” (although in the text it’s “I think perhaps all of us go a little crazy at times”) and the unforgettable final line “she wouldn’t even harm a fly…” The novel’s shower scene is far more perfunctory than that of the film, dealt with in two quick sentences (“It was the knife that, a few moments later, cut of her scream. And her head”), and Norman Bates is described as a fat, bespectacled loser who seems light years removed from Anthony Perkins, but those things certainly don’t lessen the brilliance of Bloch’s construction. Some have claimed the novel “cheats” because it presents Norman’s convos with his mother as if she’s still alive and present at his side, but the device works psychologically (and anyway is replicated in the movie in its depictions of an off-screen Norman shouting at his ma).

screenwriter Joseph Stefano’s claim that he invented the structure himself), including Norman Bates’ immortal utterance “we all go a little mad sometimes” (although in the text it’s “I think perhaps all of us go a little crazy at times”) and the unforgettable final line “she wouldn’t even harm a fly…” The novel’s shower scene is far more perfunctory than that of the film, dealt with in two quick sentences (“It was the knife that, a few moments later, cut of her scream. And her head”), and Norman Bates is described as a fat, bespectacled loser who seems light years removed from Anthony Perkins, but those things certainly don’t lessen the brilliance of Bloch’s construction. Some have claimed the novel “cheats” because it presents Norman’s convos with his mother as if she’s still alive and present at his side, but the device works psychologically (and anyway is replicated in the movie in its depictions of an off-screen Norman shouting at his ma).

…It contains everything that’s good about the flick (despite screenwriter Joseph Stefano’s claim that he invented the structure himself), including Norman Bates’ immortal utterance “we all go a little mad sometimes…”

Bloch provided a PSYCHO 2 novel in 1982. It didn’t attain the same level as the earlier book but is diverting enough on its own terms, positing that Norman Bates escapes from the mental institution where he’s long been interred by impersonating a nun, and kills Sam and Lila. From there Norman terrorizes the set of a movie being made about his crimes, a device that allows Robert Bloch to critique the slasher movie trope he helped invent.

A PSYCHO II film arrived in 1983, directed by Australia’s Richard Franklin and scripted by Tom Holland, that was radically different from Bloch’s PSYCHO 2 (the reason, apparently, for the film’s roman numeral II in place of the novel’s number 2). Here Norman Bates is let out(!) of the mental institution and returns to the Bates Motel, where it seems ma Bates is up to her old tricks. The major change from the original PSYCHO, and the Robert Bloch sequel, is that Norman is made into a sympathetic protagonist whose problems, we learn, are induced by outside agents. Not a bad movie, though PSYCHO II is still far from a great.

As for 1986’s deadening PSYCHO III, directed by Anthony Perkins himself, it again features Norman Bates harassed by his mother, and is distinguished only by a memorably creepy score by Carter Burwell (the Coen Brothers’ composer of choice) and a novel twist on the original film’s pivotal scene, with Norman-as-mother attempting another shower killing only to discover that his intended victim has already done the job herself. The made-for-cable abomination PSYCHO IV: BEGINNING arrived, unfortunately, in 1990, with Norman Bates calling in to a radio talk show to relate memories of his early years, fleshed out by Henry Thomas as young Norman and Olivia Hussey as his mother, both of whom overact shamelessly.

About the best I can say for those PSYCHO sequels is that they’re not as abysmal as Gus Van Sant’s scene-by-scene remake of PSYCHO, which stunk up movie screens in 1998. Starring a never-worse Vince Vaughn and Anne Heche as Norman Bates and Marion Crane, it adds absolutely nothing to the PSYCHO legacy, proving only that scene-by-scene remakes (Werner Herzog’s NOSFERATU notwithstanding) are a terrible idea, particularly when the movie in question is PSYCHO. Overrated it may be in my view, but it is iconic and, like most movies, horrific or otherwise, did not need to be remade.