I’ve already discerned that French and Russian horror films tend to be few and far between, but Polish horror cinema is another matter entirely. Quite simply, Poland’s genre offerings are all-but nonexistent. Poland may have given us one of the field’s most distinctive talents in the form of Roman Polanski, but his work in the horror field (REPULSION, FEARLESS VAMPIRE KILLERS, MACBETH, THE TENANT, THE NINTH GATE) was all accomplished outside his native country.

Poland has experienced its share of political upheavals, which explains why so much of its cinema is so political in nature. That includes the few existing Polish horror films, which tend to be tortured allegories with little to offer exploitation fans.

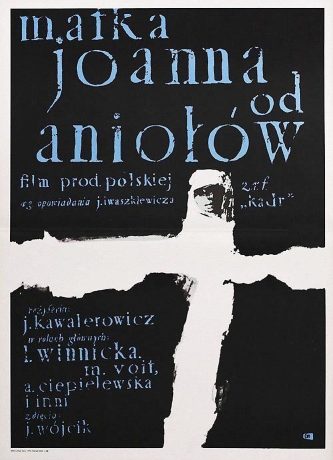

In the lexicon of Polish cinema I have yet to uncover anything worthwhile that’s horror themed prior to 1960, when MOTHER JOAN OF THE ANGELS (MATKA JOANNA OD ANIOLOW) debuted. It is arguably the most thoughtful “nunsploitation” movie ever made, with an extremely insular and intimate approach (especially in contrast to more overtly sensationalistic nunsploiters like THE DEVILS and ALUCARDA). Equally striking are the mesmerizing black-and-white visuals created by director Jerzy Kawalerowicz, who favors rigorously composed images and extremely fluid camerawork.

The narrative, inspired by a real-life incident that also fuelled THE DEVILS, is simple enough: a priest investigates the apparent demonic possession of a Mother Superior in a secluded convent, and she, or whatever is in control of her, immediately takes a shine to the priest—who in turn becomes infatuated with her. Several exorcisms transpire—the sight of a dozen or so nuns sprawled on the ground during a mass exorcism is one of Polish cinema’s most iconic images—and conclude with the priest’s humanistic plea to the demon inhabiting the Mother Superior to come into him instead. The ending is a nauseatingly happy one, but it doesn’t negate the rich, disturbing charge of all that came before.

The same year brought THE BRIDGE (MOST), an adaptation of Ambrose Bierce’s Civil War horror story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” that was made two years before Robert Enrico’s better known version. The two films, I might add, are quite close in tone and style. Both were lensed in highly atmospheric black-and-white, and set in craggy mountainous landscapes where the protagonist, a condemned man sentenced to be hanged off a bridge, manages to escape his fate–or so he thinks!

Director Janusz Majewski adds much of his own to the thirteen-minute BRIDGE, including a (somewhat superfluous) flashback in which the protagonist learns of his death sentence and startlingly impressionistic sound design. That latter element does admittedly foreshadow the shock ending, but then I’m sure we all know what happens anyway.

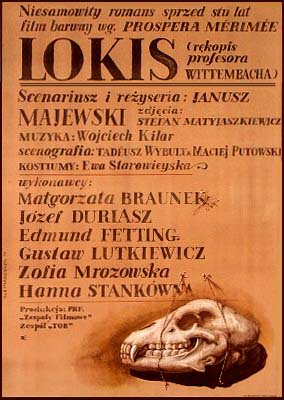

Fast forward to 1970, and perhaps the most famous Polish horror film ever made: LOKIS—REKOPIS PROFESORA WITTEMBACHA. It’s based on an 1869 Prosper Merimee tale about a young aristocrat who’s a were-bear, although it takes the protagonist, a scholarly minister staying at the bear-man’s country mansion, the entire movie to figure this out.

From the start it’s clear that director Janusz Majewski, as he proved in THE BRIDGE, has a unique and startling visual eye. The accent is on atmosphere rather than incident, with an overpowering aura of brooding mystery that builds to a chilling climax. The film is very old school, in short, which is a large part of its charm.

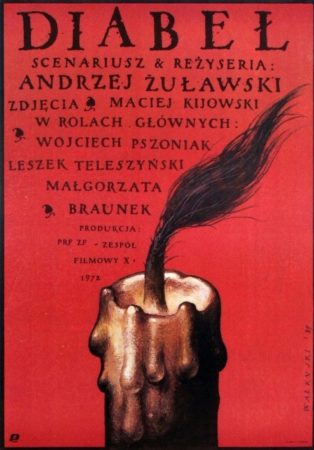

1972’s THE DEVIL (DIABEL) is a completely depraved, tasteless and over-the-top historical epic by Poland’s Andrzej Zulawski, who’d go on to craft some the most outrageous flicks of all time, including the French-made humping cucumber drama POSSESSION. THE DEVIL is in the same vein as that nutzoid classic, being a political allegory about a young man who escapes the confines of a debauched 18th Century convent through the help of a mysterious dark robed stranger (who represents Poland’s corrupt establishment). What transpires is a nightmarish trek through a truly psychotic landscape, with the protagonist learning that his dad’s been killed, his mom’s become a prostitute and everyone around him is totally insane. He inevitably becomes deranged himself, and takes to killing everyone he sees with a straight razor, all with the help of that mysterious stranger.

The spastic camerawork that characterizes so many of Zulawski’s later films is in full bloom here, along with overtly hysterical performances and much unflinching gore and sex. I’m not entirely sure that it all adds up to much (there’s a totally out-of-left-field twist at the end that does nothing but further confuse matters), but the film is an exhilarating viewing experience for those who can stomach its excesses. It was apparently banned in its homeland until 1988, and then given a very sporadic release.

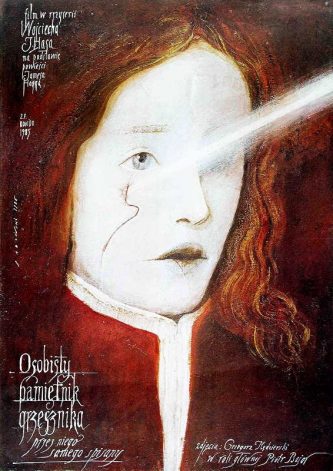

1986’s MEMOIRS OF A SINNER (OSOBISTY PAMIETNIK GRZESZNIKA PRZEZ NIEGO SAMEGO SPISANY), the second-to-last film by THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT’S incomparable Wojciech Has, is an unusually opulent adaptation of James Hogg’s gothic classic. It concerns a man who’s resurrected from the dead by a gravedigger. The talking corpse proceeds to relate how he was encouraged by the Devil to kill his brother; this he did, and afterward suffered severe reality dislocation as a malevolent double went about committing crimes in the man’s name. The whole thing is extremely slow moving and message heavy—like the novel, it’s concerned with the vagaries of hypocrisy, specifically the concept of “justified” sin—but it has a gorgeously gothic look, and the second half, in which reality and hallucination become increasingly blurred, exerts a trippy fascination.

Finally we have 1996’s astonishing SZAMANKA, another Andrzej Zulawski freak-out that’s very likely his foremost accomplishment. It centers on the mummified remains of an ancient shaman, unearthed by a sex-crazed anthropology lecturer (Boguslaw Linda). Said lecturer takes up with an equally nutty young woman, unforgettably essayed by newcomer Iwona Petry. Petry’s uninhibited performance is one of the highlights of the film: smolderingly sexy yet also deeply unhinged and downright scary.

Finally we have 1996’s astonishing SZAMANKA, another Andrzej Zulawski freak-out that’s very likely his foremost accomplishment. It centers on the mummified remains of an ancient shaman, unearthed by a sex-crazed anthropology lecturer (Boguslaw Linda). Said lecturer takes up with an equally nutty young woman, unforgettably essayed by newcomer Iwona Petry. Petry’s uninhibited performance is one of the highlights of the film: smolderingly sexy yet also deeply unhinged and downright scary.

As Linda’s obsession with the shaman grows more encompassing (the corpse actually sits up and speaks with him at one point), his relationship with Petry degenerates into a series of freaky sexual encounters that culminate in an unspeakably brain-fried finale, the details of which I’ll leave you to discover for yourself. The whole film, in fact, must simply be experienced, as no words can possibly do justice to the amazing boldness of Zulawski’s vision.