Ingmar Bergman’s PERSONA: not a true “horror” film perhaps, but certainly one of the cinema’s most potent explorations of fear, apprehension and discontent. Released in 1966, it’s a dark, vexing and altogether mysterious work with possible supernatural overtones. It marked a break with Bergman’s previous films, which consisted largely of quasi-naturalistic dramas (MONIKA, THE SILENCE) and eccentric fantasies (THE MAGICIAN, THE SEVENTH SEAL), paving the way for the oft-horrific psychodramas (HOUR OF THE WOLF, THE PASSION OF ANNA, CRIES AND WHISPERS) that typified his output throughout the remainder of the 1960s and 70s.

Ingmar Bergman’s PERSONA: not a true “horror” film perhaps, but certainly one of the cinema’s most potent explorations of fear, apprehension and discontent. Released in 1966, it’s a dark, vexing and altogether mysterious work with possible supernatural overtones. It marked a break with Bergman’s previous films, which consisted largely of quasi-naturalistic dramas (MONIKA, THE SILENCE) and eccentric fantasies (THE MAGICIAN, THE SEVENTH SEAL), paving the way for the oft-horrific psychodramas (HOUR OF THE WOLF, THE PASSION OF ANNA, CRIES AND WHISPERS) that typified his output throughout the remainder of the 1960s and 70s.

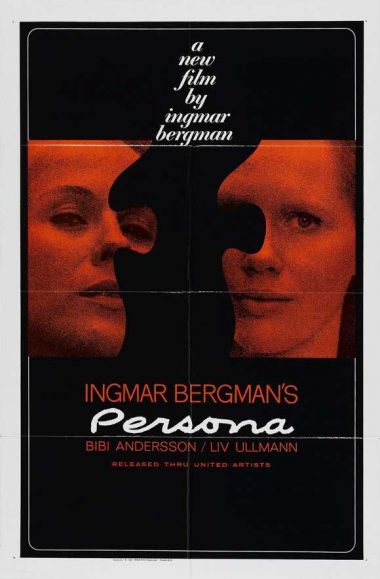

In PERSONA the outgoing nurse Alma (Bibi Andersson) is charged with taking care of the famous actress Elisabet (Liv Ullmann), who has for some reason stopped speaking. The admitted inspiration for this account was the one act play THE STRONGER by Bergman’s hero August Strindberg, in which a female chatterbox, identified only as “X,” is severely unnerved by the silence of her companion “Y,” who proves herself the stronger of the two characters merely by keeping quiet. Like “X,” Alma is apprehensive from the start, correctly sensing in Elisabet a reservoir of formidable strength and intelligence. The two retire to a small house on a secluded island, where a strange atmosphere holds sway in which Elisabet, despite her muteness, asserts her will on the hapless Alma, dramatically reversing the ladies’ respective roles. It all culminates in one of the oddest yet most widely quoted film images of all time: a close-up of Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann’s faces literally fused together.

Influenced as much by the new wave film movements of the 1960s as it was by Strindberg, the film is typified by discordant editing and highly self-conscious camerawork that constantly reminds us we’re watching a movie. Bergman makes that point literal on several occasions via shots of celluloid running through a projector, a film break and so forth, which provide the closest thing there is to an explanation for all the insanity.

Roman Polanski once said of Bergman that he “seemed to follow the principle that anything too easy to grasp is flat and boring. His remarkable talent was that he could leave his audience with the feeling that if they hadn’t fully grasped the complications, it was their fault.” I’d argue that Bergman’s conceptions were in fact quite easy to grasp, but presented in highly complex frameworks that portended otherwise (or, as Howard Stern put it, “I went through a chess game with Death to find out that life is strawberries and cream?”).

PERSONA, in truth, couldn’t be simpler, with Alma and Elisabet existing as two portions of a whole. That whole is represented by a sickly boy who in an early scene stares straight into the camera—at us—which is revealed, in a reverse angle, to be the faces of Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann fading into one another. This scene is repeated at the end of the film, suggesting that everything we just viewed was a hallucination experienced by the boy—or, more accurately, by Ingmar Bergman.

The film, in short, is a fascinating and frustrating viewing experience unique in cinema history. Kudos to Bergman, his lead actresses, and cinematographer Sven Nykvist, whose evocative black and white cinematography is superlative. Their efforts have resonated through the years in literature—Joyce Carol Oates’ 1985 novel SOLSTICE, about the ambiguous bond between two women, owes a debt to PERSONA—and especially in films, such as:

PERFORMANCE (1970), whose writer and co-director Donald Cammell was admittedly under the spell of Bergman’s masterpiece (note the similarities in the titles). Cammell and co-director Nicolas Roeg add a goodly amount of late-sixties flamboyance in place of Bergman’s spare black and white visuals, with a macho hit man (James Fox) and an androgynous rock star (Mick Jagger) exploring one another’s “acts” with the aid of psychedelics during a weekend sojourn at Jagger’s secluded apartment. PERFORMANCE has proven quite influential over the years, siring films like CORRUPT (1983) and APARTMENT ZERO (1988), but it’s a fact that without PERSONA neither it nor they would exist.

THREE WOMEN (1977), which likewise expands upon Bergman’s bare-bones art direction with a visually rich and unexpected setting: a funky retirement community in the California desert where two women, one an overbearing control-freak (Shelley Duvall) and the other a childlike free spirit (Sissy Spacek), undergo a quasi-mystical drama of personality transference. As the title signifies, there’s a third lady in the form of a mysterious artist (Janice Rule), but in actuality it’s a two woman show with a surreal veneer that, mixed with Altman’s trademark observant naturalism, adds up to a wonderfully strange concoction—albeit one that won’t seem entirely unfamiliar to viewers of PERSONA.

ANOTHER WOMAN (1988) saw longtime Bergman devotee Woody Allen (who previously included a PERSONA-inspired shot of meshed-together faces in 1975’s LOVE AND DEATH), craft his very own PERSONA wannabe. It was the third of Allen’s Bergman inspired snooze-fests (following INTERIORS and SEPTEMBER) centered on overprivileged Manhattan-based dweebs. Here the focus is on a middle-aged novelist (Gena Rowlands) overhearing the confessions of a distressed pregnant woman (Mia Farrow) in a psychiatrist’s office. Farrow’s recollections trigger Rowland’s own memories, which parallel those of Farrow—and PERSONA’S Alma. There’s also a lengthy dream sequence and an eventual face-to-face meeting between the two ladies, which as any Bergman viewer well knows will have none-too-subtle repercussions. Another PERSONA connection is cinematographer Sven Nykvist, whose drab visuals here fall far short of his work with Bergman.

SINGLE WHITE FEMALE (1992): It may seem inappropriate, if not downright sacrilegious, to equate Ingmar Bergman with this Hollyweird goof, but PERSONA has been cited by SWF’s director Barbet Schroeder and screenwriter Don Roos as a template—and indeed, were PERSONA to be remade as a mainstream thriller the results would likely play very much like this film, whose outgoing heroine (Bridget Fonda) finds her mousey roommate (Jennifer Jason Leigh) literally taking over her life by stealing her identity. The final shot, of a photo of Fonda and Leigh’s faces fused together, completes the connection.

MULHOLLAND DRIVE (2000): It’s no secret that this David Lynch mindbender began life as a rejected TV pilot that was fleshed out to feature length. I’m guessing Lynch was watching PERSONA when he did the fleshing-out, as it was the clear antecedent for MULHOLLAND DRIVE’S main plot thread, involving a wannabe actress (Naomi Watts) and a mysterious amnesiac (Laura Elena Harring) who come together and eventually exchange guises.

SWIMMING POOL (2003) is an eccentric thriller by the French auteur Francois Ozon, who provides us with yet another pair of mismatched ladies—Charlotte Rampling as a steely middle-aged novelist and Ludivine Sagnier as a carefree flirt-–undergoing a hallucinatory riff on themes of power and identity.

MELANCHOLIA (2011) was made by Bergman’s fellow countryman Lars von Trier. A shameless film nerd in addition to a world renowned auteur, von Trier explicitly references LAST YEAR AT MARIENDBAD and Andrei Tarkovsky’s SOLARIS in this film, but it seems PERSONA was his main inspiration. MELANCHOLIA can almost be viewed as a parody of Bergman’s masterpiece, with its pair of sibling heroines, one a clinically depressed nut (Kirsten Dunst) and the other a well-adjusted homemaker (Charlotte Gainsbourg), switching roles when a runaway planet threatens the Earth. In the ensuing chaos Gainsbourg goes to pieces while Dunst proves disarmingly level-headed.

Of course none of those films, potent though many of them are, succeed in capturing a shade of the complexity and artful puzzlement of PERSONA, which after nearly fifty years retains its precedent-setting brilliance and overpowering air of haunting mystery. If the abovementioned films prove anything it’s that PERSONA will never be matched in the coming years, much less bettered.